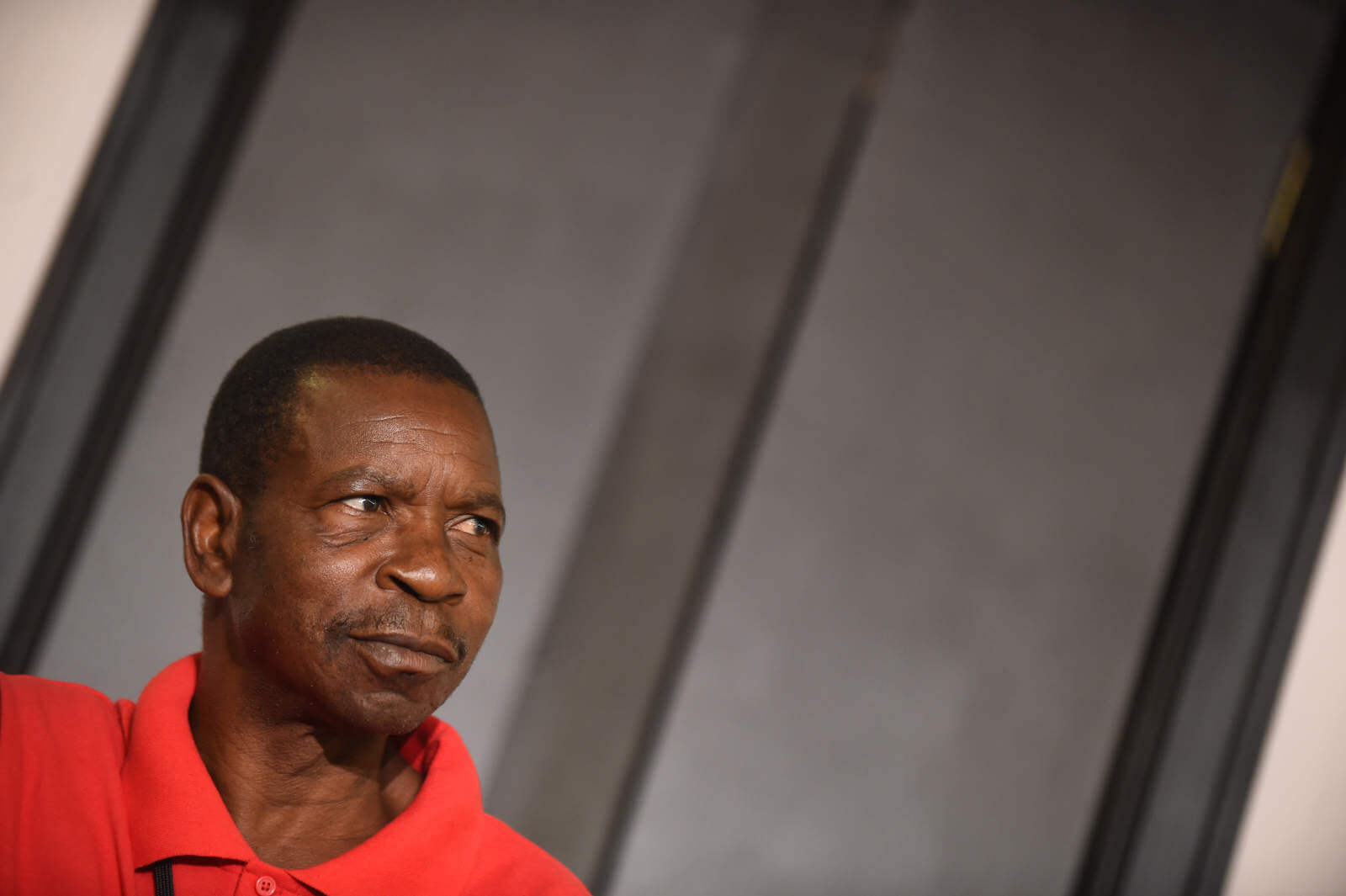

Seventeen years ago, Chris Muwani migrated from Zimbabwe to South Africa, where he works on a tomato farm. If he does not fulfill his daily quota, he is not paid for the day. So to complete his workload, he typically does not walk the long distance to access the toilet or fresh water. Muwani frequently is called derogatory names because he is from Zimbabwe, and says “even my kids are discriminated against. The kids tell them, ‘We will not play with you guys, you are not worthy of us as friends.”

For migrant workers and their families across South Africa, such abuse based on nationality or ethnicity is a daily event that periodically erupts into full-blown xenophobic attacks. Earlier this year, South Africans in townships and villages across the country joined in a series of violent protests that targeted Nigerians and looted and shut down more than 30 stores belonging to Somalis, Pakistani and other migrants in townships around Pretoria and parts of Johannesburg. Protestors blamed migrants for creating crime and trash, involvement in drug cartels and prostitution, and lacking respect for their host country.

There was no loss of life—this time. But at least 66 migrant Africans in South Africa were killed in xenophobic attacks between January 2015 and January 2017, according to the African Center for Migration and Society.

While Western-oriented media and policymakers focus on the plight of migrants from Africa to Europe, the majority of the 34 million African migrants are in search of decent work across borders within the continent, often toiling in the most dangerous, unregulated jobs where they are paid little and have few rights. Only 25 percent of African migrants are in Europe.

The search for jobs drives millions of African migrants out of their home countries, and many to South Africa. But the complex origins of the discrimination and xenophobia they face on the job and in their communities offer historians an opportunity to move beyond the “rising tide of populism” meme and toward a deeper analysis that eschews a Western-centric view of politics, culture and the working class, and invite us to more deeply interrogate the roots of ethnic, national and cultural divisions. Ideally, this article launches such a conversation, and points to avenues for detailed research.

Few Jobs, Poverty Wages

Young workers in African countries, as elsewhere, are disproportionately affected by lack of employment. Nearly half of the 10 million graduates of the more than 600 universities each year in Africa do not get jobs. The African region has the world’s highest rate of working poverty—people who are employed but earning less than $2 a day.

Further, the rapid decline of formal-sector jobs in African countries like Zimbabwe, where more than 90 percent of workers toil in the informal economy, mean massive numbers of workers labor in unsafe conditions, making low wages, with no social safety protections. In Africa, the rise of precarious informal-economy jobs like market vending, domestic work and “artisan” (unregulated) mining, has seen more workers unable to support their families and forced to migrate, many to South Africa, the continent’s most industrialized economy. Some 75 percent of migrants to South Africa come from four countries: Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Lesotho and Malawi.

More than Competition for Jobs

In South Africa, as in countries around the world, the scrabble for family-supporting jobs in an ever-decreasing pool of employment opportunities presents a ready-made explanation for opposition to migrant workers. In 2010, a survey found that 60 percent of South Africans believed that migrants take jobs. Only 27 percent said migrants created jobs, although a study of migrant entrepreneurs from Somalia, Nigeria and Senegal living in Cape Town found that 96 percent employed South Africans.

South Africa’s rising unemployment and lack of jobs for new graduates—who face an unemployment rate of 65.5 percent—on the surface point to the rising tension directed at migrant workers.

Yet at the same time, the number of foreign-born people in South Africa has decreased steeply, from 2.2 million in 2011 to 1.6 million in 2016, a sufficiently large quantitative decline that seemingly would decrease, rather than increase anti-immigrant sentiment.

Other factors also complicate the extent to which opposition to migrant workers is driven by, or is justification for, a perceived competition for jobs.

Unwrapping Xenophobia

Notably, migrants have faced violent attacks in South Africa since apartheid ended in 1994. Yet “few perpetrators have been charged, even fewer convicted. In some instances, state agents have actively protected those accused of anti-foreigner violence,” according to Jean Pierre Misago, a researcher with the African Center for Migration and Society.

Large-scale violent outbreaks against migrants have erupted periodically since, with mob violence in 2008 resulting in the deaths of 62 people, including South Africans, and the displacement of more than 100,000 people. Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuave, a national from Mozambique, was beaten, stabbed and set on fire.

Further, migrants are ongoing targets of corrupt officials. Drawn in part by South Africa’s model constitution, which grants migrants seeking asylum many of the same rights as South Africans, migrants find the reality much different after they arrive. Some one-third of migrants experience corruption at South African refugee registration offices, according to a 2015 study.

Migrant domestic workers I interviewed pointed to rising cost of work permits that make it virtually impossible for them to afford to work legally, as well as employer abuse of the system. “When our employers know our permits are expiring, they don’t pay you,” says Prexedes, 41, a domestic worker from Zimbabwe.

Another key factor that must be considered is the role of gender. Nearly half of all African migrant workers are women, with the feminization of migration increasing in Africa over the past few decades as women seek to support their families. Like women migrants everywhere, they disproportionately are exploited throughout the migration process—facing violence as they cross borders, including sexual assault, and once in the destination country, typically can secure only the lowest-paying, most difficult jobs.

Going Forward

In a study of the 2008 violence, researchers at the Southern African Migration Program assert that economic insecurity “does not explain why only certain groups were and are singled out for deadly assault.” Rejecting a “neo-Marxist” materialist explanation for the violence, the authors further note:

“If economic competition between poor residents and migrants is the underlying cause of aggressive hostility, it does not explain why wealthy and privileged groups, who do not face direct or even indirect competition from these migrants, also espouse these prejudices.”

Policy analysts, political scientists, sociologists, ethnologists, and other scholars have explored migration within an African context. Missing is an historical perspective—especially one focused on the issues surrounding labor migration.

The author, an independent historian, conducted interviews and drew some of her research for this article from her work as Senior Communications Officer at the Solidarity Center, an international worker rights organization. This article does not necessarily represent the views of the Solidarity Center.