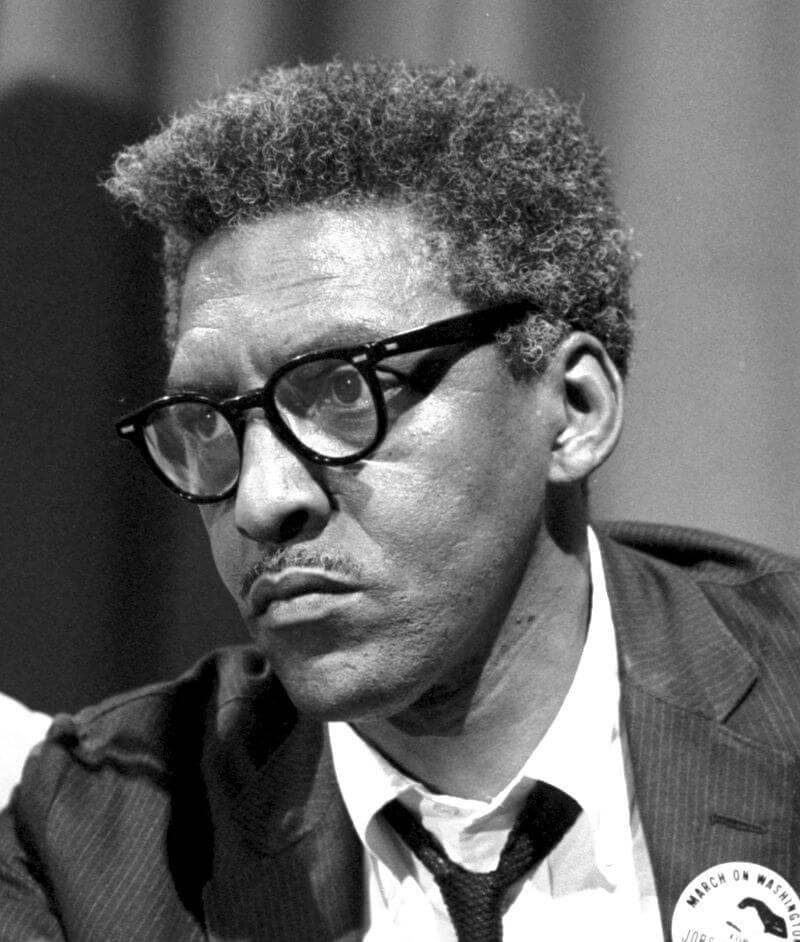

“I can’t breathe” actions in street crossings, sports fields and other civic spaces have blown new life into civil rights public history. Demonstrators seek their antecedents, and scholars are eager to remedy America’s amnesia of past struggles against police violence. But bygone reformers and rebels won little. Activists hoping for better this time might heed one forebear in particular: Bayard Rustin.

In 1965, when the taste of victory over de jure segregation was still fresh, the great Movement strategist published a sobering assessment of civil rights’ future. Activists were not going to win further progress, he argued, without a major shift in tactics. Central to Rustin’s thesis was his insight that recent achievements owed not just to the moral impetus of protests, but also to the vulnerability of targeted policies. “[W]e hit Jim Crow precisely where it was most anachronistic [and] dispensable … – in hotels, lunch counters, terminals, libraries, swimming pools, and the like,” he wrote. “For in these forms, Jim Crow … impede[s] the flow of commerce.” Remaining inequities such as unemployment and de facto school segregation were “more deeply rooted in our socio-economic order” and would “not vanish” easily. This was painfully prophetic.

To make sense of Rustin’s analysis, we need to ask, “anachronistic and dispensable” for whom? Jim Crow in public accommodation was not of trivial importance for all white people: witness the vicious attacks on Freedom Riders and sitters-in. But it was dispensable for the white upper crust. This can be seen in the Movement’s signal campaign, the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Within days of the boycott’s launch in December 1955, bus company executives had done their arithmetic and recognized that a 75 percent drop-off in ridership was unabsorbable. They expressed openness to the black community’s demand (which at that stage was for a more flexible segregation protocol rather than desegregation). Weeks later, local business owners also tried to broker a compromise.1 But they were dismissed by city officials beholden to a larger white electorate, including bus drivers, the whites who actually rode the buses, and others who felt their status at stake. Ultimately it was court action not economic pressure that pried the “white” and “colored” signs from Montgomery’s buses. Federal judges, like Montgomery’s business class, decided that those relics were dispensable.

How does Rustin speak to the current movement? By prompting us to analyze the targeted practices and consider who sees them as dispensable – and who does not. In New York, the place of Eric Garner’s suffocation, protesters have demanded repeal of two city policies: “broken windows policing,” the NYPD tenet that warranted Garner’s arrest for selling loosies; and implicit impunity for officers who violate the Patrol Guide’s ban on chokeholds. They have also called for the appointment of special prosecutors in cases involving allegations of police abuse. The first two policies are prerogatives of the police commissioner, who answers to the mayor. The third would require a change in state law.

Who sees the existing policing regime as indispensable? New York police officers, most visibly. Their investment, like that of Montgomery’s bus drivers, is partly in status. But it is also in job security. Hence their demand for impunity in the Garner case and similar ones, and their support for programs, like broken-windows, that require a massive blue presence on every street where loose cigarettes are sold. Indeed, police union leader Patrick Lynch, currently in the news for blaming Mayor de Blasio for the December murder of two officers, also excoriated the law-and-order Mayor Giuliani for failure to augment NYPD rolls in the 1990s.

Some officers dissent from Lynch’s line; some have even tried to blow the whistle on the department’s arrest quotas. These cops deserve recognition and support from the anti-brutality movement.

But the policing regime’s constituency extends far beyond the NYPD. It includes swaths of the upper working- and lower middle-classes – predominantly but not lily white – who identify with the cops they count as neighbors, relatives, friends. (Staten Island, where a grand jury refused to indict the officer who choked Garner, is a prime example.) It includes corrections officers, prison stockholders and others who profit from the prison-industrial complex. It includes district attorneys who view the special prosecutor fix as an impugnment of their integrity and a hindrance on their horse-trading.

It includes legislators on both sides of the aisle. Look at Albany lawmakers’ overwhelming passage of a bill to bring the city jail on Rikers Island, formally part of the Bronx, under the jurisdiction of the presumably cop-friendlier district attorney of Queens. The bill was pushed by corrections officers (a majority black workforce in New York City), whose union president belongs in the Khutzpah Hall of Fame. (It was vetoed by the centrist Governor Cuomo.)

Less widely recognized, the status quo’s constituency includes liberal officials. Notwithstanding the vitriol that Gotham cops have directed at de Blasio, the mayor has met none of the anti-brutality movement’s concrete demands. (It was his lip service, given in a statement about the danger his own son might encounter in police hands, that earned him the “backs in blue” treatment.) His inaction may reflect a budgetary calculus: the Daily News reports that public officials are not keen to forego the $8.7 million that broken-windows tickets (a.k.a. “quality of life” summonses) bring into city coffers. This analysis is questionable, since $8.7 million is crumbs out of New York’s $75 billion budget pie. But if de Blasio is not counting dollars, he’s surely counting votes and figuring that the support of middle-class centrists, many of whom welcome the public order that aggressive policing promises to maintain, is neither anachronistic nor dispensable for a mayor who is in other respects committed to serving the poor and the colored.

Cops are not ignorant of this math. Their latest protest tactic is a slowdown that amounts to a de facto repeal of broken-windows. It may look like a concession to the anti-brutality movement, but it’s also a yank on the mayor’s fiscal and political chain.

Further, even the segment of de Blasio’s base that is most solidly critical of police violence has some investment in police presence. Legal scholar James Forman, Jr. points out that because violent crime bears most heavily on the black poor, ghetto residents often support tough-on-crime policies despite their misgivings about mass incarceration.2 The same is true with petty and mid-level offenses. Drug-dealers and teenaged partiers don’t set up shop in the hallways of posh buildings staffed by doormen in New York; they operate in the projects and low-rent private buildings where security is nil. And when residents of such buildings seek relief, they have few options beyond “vertical patrols” conducted by the NYPD. My own low-income, majority-minority building was enrolled in the patrol program at the request of tenants. Nobody here wants trespassers (let alone legal residents) to be choked or shot, of course. But police are not exactly wrong when they say that they’ve been asked in.

Bayard Rustin would not give up. Having himself endured police violence and a stint on a chain gang, he would feel the urgency of the current movement. But he would also recognize its challenge: dismantling policies in which a diverse array of citizens and politicians is invested both psychically and materially. In his 1965 article, he argued that blacks needed to ally strategically with white liberals and the labor movement if they were to tackle inequities “deeply rooted in our socio-economic order.” What might this kind of thinking mean today?

There are no easy answers. It is not unimaginable that the NYPD’s own rank and file might accept reasonable checks on the use of force in return for improved working conditions, specifically, a redefinition of “productivity.” Notwithstanding the union leadership’s knee-jerk defense of stop-and-frisk and broken-windows, many officers would rather be chasing what they regard as real criminals than locking up petty offenders. This is precisely what motivated the whistle-blowers cited above. And the same officer who wrote to the Times justifying “backs in blue” for de Blasio listed productivity speed-ups as a major drain on morale. I’ve heard directly from a number of cops, whom I know through my paramedic work, that they despise the monthly arrest quotas for jay-walking and the like. Famed whistle-blower Frank Serpico has publicly expressed faith in ordinary officers’ better angels.

Similarly, decent-hearted corrections officers might support certain changes. The rampant brutality at Rikers, hateful in its own right, only worsens a work environment made grim enough by the 40 percent mental illness rate among inmates. (A recently-filed federal lawsuit may take union intransigence out of this equation. It seems to have disposed de Blasio to butt heads with Norman Seabrook in a way he hasn’t done with Pat Lynch.)

That still leaves the other investors – the ones who wear suits rather than blue uniforms. Here the anti-brutality movement is up against the same problem that hinders so many democratic efforts, namely, a deregulated campaign finance system that renders officials more accountable to donors than to ordinary voters. Can the movement make “broken windows money” politically toxic, as the climate justice movement is seeking to do with oil money, by publicizing the political spending of prison companies and police unions? Can it teach the public that excessive policing serves as an undeclared tax on the poor? Can it find other ways to make unchecked policing a bad investment? Can it give members of de Blasio’s governing coalition who are not directly invested in this issue a reason to care? Or is its only resort the federal bench? To use Rustin’s framework, how can current policies be made to seem dispensable to those in power?

To win concrete reforms, the anti-brutality movement must harness moral power to political savvy. Rustin’s insights bear remembering.

1 Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1987), 79.

2 James Forman, Jr., “Racial Critiques of Mass Incarceration: Beyond the New Jim Crow,” New York University Law Review Vol. 87, 115-20.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.