April 2017 marks the 100th year anniversary of U.S. entrance into World War I. Doubtless most of the commemorations of this event will focus on the significant legacies of the war for international political configurations and for the future U.S. political and military role in the world. Yet labor historians and activists also need to use the anniversary of the so called “Great War” to take stock of its significance for U.S. workers. To date, historians have focused most attention on the decision of the AFL leadership to support the U.S. war effort, and on the subsequent appointment of many AFL leaders to government war boards. These appointments, as Joseph McCartin has shown, helped to fuel the development of an industrial arbitration system that would dominate U.S. labor relations for much of the twentieth century. Yet the war bitterly divided workers both in the United States and abroad and provoked a powerful counter-reaction against the Wilsonian internationalist agenda at war’s end.

Continuing divisions among U.S. labor activists about whether the liberal capitalist values embodied in the Wilsonian vision really served the class interests of workers would influence the course of U.S. labor internationalism throughout the twentieth century. Most recently, working-class disillusionment with the Wilsonian world vision has manifested itself in the activism of groups such as U.S. Labor Against the War, created to oppose the U.S. occupation of Iraq in 2003, and in the strong working-class backlash against the Democratic Party’s economic internationalism in the recent presidential election.

During the early twentieth century, the Second International, composed primarily of European socialist and labor organizations that sometimes included U.S. representatives, often declared its opposition to bourgeois and imperialist wars and discussed tactics for opposing such wars. Yet proposals for a general strike in the event of the outbreak of war were voted down and constituent groups failed to agree upon any other concrete plans of action to stop war. Following the cascading series of events that led European powers to declare war against each other in August 1914, labor and socialist organizations in belligerent countries found themselves in a conundrum. They opposed the war in principle, but had no unified plan for ending it.

Most European labor and socialist groups thus reluctantly chose to support their nations’ war efforts in order to avoid government repression and to protect workers’ rights during wartime. By contrast, the prolonged period of U.S. neutrality between August 1914 and April 1917 afforded American workers and labor activists a unique opportunity to debate the war and to develop plans for thwarting U.S. intervention in the conflict in venues that ranged from neighborhood union halls and city labor councils, to Socialist street rallies, immigrant fraternal meetings, national trade union conventions, and the pages of the vibrant labor and socialist press.

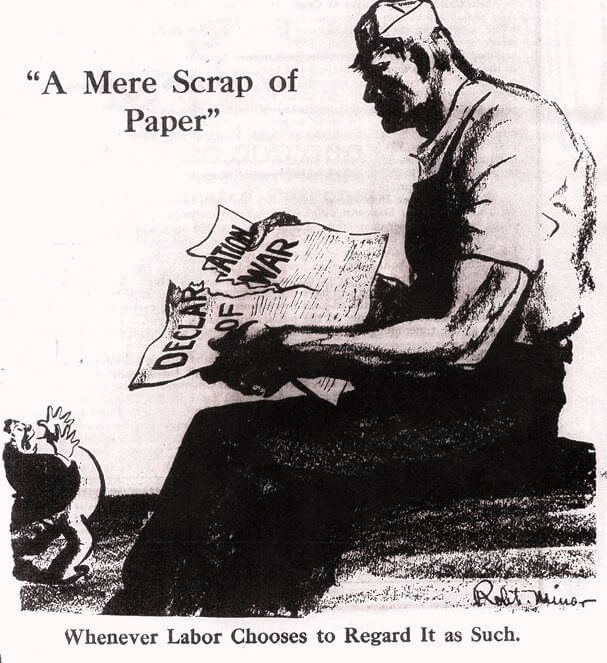

Working-class critiques of the war were as diverse as the U.S. working class itself. European immigrants often vehemently disagreed among themselves about which nation was most responsible for causing the war; significant regional, occupational, and political differences divided even native-born workers. Yet several themes predominated in working-class circles that rarely reverberated in the corridors of the White House. Workers throughout the country argued that the war was a “rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight. “ European nations, they believed, were warring against each other in order to protect the economic interests of their capitalist classes, yet it was workers who were disproportionately fighting and dying in the brutal trench warfare that quickly became the hallmark of the conflict. Similarly, they argued that it was the American capitalist class that lay behind the effort to increase U.S. military preparedness and to involve the United States in the war. When preparedness groups lobbied on behalf of an increased defense budget and universal military training, labor and Socialist groups from coast to coast staged counter-preparedness and antiwar rallies and filled the pages of the labor press with anti-militarist articles and cartoons.

Mr. Block learns about war. The Industrial Workers of the World was the radical alternative to the American Federation of Labor.

Preparedness activists argued that a stronger military would help prevent U.S. involvement in the war by discouraging European attacks on American soil. Military training, they argued, instilled citizenship values in American men and revived their sagging masculinity. By contrast, Socialist and labor activists expressed doubt that any European attacks on American soil were imminent and argued that the proposed military training programs were actually designed to inculcate blind obedience to capitalist authority among working men. The new military forces, they argued, would be used not only on the battlefields of Europe but also to suppress strikes at home.

When President Wilson argued that German submarine attacks on American ships were a threat to U.S. national security, many labor activists and Socialists argued that Wilson’s evolving definition of national security revealed a class bias. Such attacks, they pointed out, were not an imminent threat to working people but rather to the profits of American businessmen. Even more troubling from the perspective of labor and Socialist activists was Wilson’s insistence on defending the rights of wealthy American passengers to travel through war zones on belligerent ships in order to vacation or to conduct business in Europe. Following the German sinking of the British passenger ship the Lusitania that resulted in the deaths of 128 Americans, talented Socialist and labor cartoonists such as Robert Minor offered penetrating satires like the one below depicting Wilson as beholden to big business interests and out of touch with working people.

Yet U.S. labor activists, like their counterparts in Europe, ultimately divided over how to prevent U.S. intervention in the war. The Industrial Workers of the World and some left-wing Socialists sought to develop a plan for a general strike in the event that the Wilson administration declared war. The foremost promoters of this plan, however, soon came to the conclusion that the labor movement was too organizationally immature to support such a strike. More moderate Socialist and labor activists favored a constitutional amendment requiring democratic referenda that would include disenfranchised women on all questions involving U.S. intervention in foreign wars. Some also favored a referenda on whether the government should impose an embargo on U.S. exports to Europe in order to prevent further attacks on American ships. Lives, they insisted, were more important than profits. Still others continued to pursue more traditional methods of opposing possible intervention in war, such as lobbying Congress and the President and trying to influence public opinion through protests and antiwar writings. Those who engaged in these latter types of actions often argued that U.S. business interests led the Wilson administration to pursue policies that favored Britain more than Germany. By adopting more balanced policies, they insisted, Wilson could assuage Germany, in turn making it more amenable to compromises on the issue of submarine warfare. Particularly prominent in this group were Irish-American labor activists, who loathed Wilson’s tilt toward Britain and argued that that the United States had no vested interest in allying with an imperial power that suppressed the rights of workers in colonial areas across the globe.

Yet when Germany declared that it would resume unrestricted submarine warfare in late January of 1917, the Wilson administration chose to sever diplomatic relations with Berlin. German U-boats continued to sink American ships throughout the winter of 1917, and on April 2, Wilson asked Congress to declare war against Germany. Wilson’s war address is often remembered primarily for its idealistic pledge to make the world “safe for democracy.” Yet many labor and socialist dissidents expressed skepticism about this goal, noting Wilson’s paternalistic record of intervening in Latin American affairs and also expressing doubts that democracy could ever be imposed on one nation by another. Socialist and labor activists noted another troubling theme in the speech. Wilson also argued that the United States had a special responsibility to defend those tenets of international law which guaranteed that the “free highways of the world” remained open to neutral powers seeking to maintain their commerce during wartime. This open-ended pledge seemed to suggest that Wilson was more interested in making the world safe for capitalism than democracy. Such a pledge might immerse the United States in endless wars to guarantee the profits of American businessmen.

Although strong antiwar currents continued to course through every layer of the labor movement during the weeks leading up to and following Wilson’s declaration of war, AFL President Samuel Gompers had undergone a metamorphosis in 1916. Initially opposed to U.S. involvement in the war, Gompers reversed himself and chose to support increased military preparedness in 1916. A British immigrant, Gompers increasingly agreed with Wilson that Germany was the greater violator of international law. Equally significant, Gompers had watched with interest the partnerships that developed between the government and labor in belligerent countries during the war and believed that U.S. labor had more to gain than to lose in supporting government policies if the U.S. became involved in the war. Finally, Gompers, as an ex-socialist, was sympathetic to Wilson’s international economic vision. Like Wilson, he believed that U.S. capitalism required foreign markets to survive and that it was therefore in the international interest of American workers to support international policies designed to keep commerce flowing during times of war as well as of peace.

Wilson rewarded Gompers for his loyalty by appointing him to serve on the Council of National Defense in late 1916. At the urging of council members who were concerned about continued pacifist tendencies within labor, Gompers in March of 1917 staged a carefully orchestrated meeting of national and international union leaders who pledged labor’s loyalty to the government in the event of U.S. involvement in the war. Critics complained that these AFL leaders had no authority to speak for AFL members and that no referendum had been held within the ranks of labor on the war issue. Yet Gompers used the meeting to assert that the AFL was solidly behind the war effort. In return for his efforts, Gompers and other AFL leaders were appointed to additional war boards and the Wilson administration worked with them to develop a system of industrial arbitration designed to prevent strikes for the duration of the war. By contrast, the majority wing of the Socialist Party continued to oppose the war and developed an incisive critique of the draft emphasizing that it was un-American and violated the thirteenth amendment outlawing slavery. Due at least in part to Socialist efforts, opposition to the draft and draft-dodging within the ranks of labor remained strong and high levels of strike activity persisted, prompting the Wilson administration to use the Espionage and Sedition Acts to crush dissent.

In the aftermath of the war, Gompers would be further rewarded by the Wilson administration for his loyalty with an appointment to serve on a special commission on International Labor Legislation at the Versailles Peace Conference. This body developed an unprecedented labor bill of rights that was incorporated directly into the peace treaty and also created the International Labor Organization (ILO). This organization was to be comprised of business, labor, and government representatives from constituent countries. Its goals were to encourage international cooperation to reduce industrial strife and economic nationalism in ways that would facilitate the free flow of commerce and investments so vital to international capitalism. Since the new organization also gave labor an unprecedented voice in international governance, both Wilson and Gompers assumed it would be a selling point among U.S. workers in winning their support for the Versailles Peace Treaty. Wilson extensively used the labor bill of rights and proposed ILO to promote the Versailles Peace Treaty in his whistle stop tour of the United States in 1919.

Yet Wilson and Gompers badly miscalculated. Both the labor provisions of the Versailles Treaty and the proposed ILO proved quite controversial among labor and Left activists and helped swell the tide of opposition to the treaty in ways that have been insufficiently understood by historians. Most accounts blame the lack of working-class enthusiasm for Wilson’s projects at Versailles on frustration over wartime repression and on domestic economic concerns. These factors, historians assume, also lay at the heart of the Republican victory in 1920 which sealed the fate of the Versailles Peace Treaty and permanently prevented U.S. membership in the League of Nations.

But another important factor shaping the postwar alignments of U.S. workers was an influential Left critique of the economic internationalism that undergirded Wilsonian foreign policy throughout his term in office. Elements of this critique were shared by Socialists, Communists, Wobblies, Labor party activists and even some otherwise conservative bread and butter trade unionists committed to national independence for former homelands. Wilson, charged his labor and Left critics, had gone to war not to make the world safe for democracy but to make it safe for capitalism. At the peace conference, he had worked hard to create a concert of powers among leading capitalist and imperial powers at the expense of those colonial peoples seeking their independence at war’s end. With the imperial division of labor still largely intact, they argued, any economic integration promoted by the ILO and League of Nations might prove more harmful than beneficial to American workers, especially given that the structures of these organizations fell far short of being genuinely democratic. Such concerns dovetailed with those of the Republicans and it would be pro-labor Republican Senator Robert LaFollette who led the attack on the ILO in Congress.

Although opponents of Wilson on both the political Left and Right helped to defeat the Versailles Peace Treaty and prevent U.S. membership in the League of Nations and ILO, Wilsonian internationalist ideas remained influential in American politics over the course of the next century. The Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration, after at first toying with economic nationalism in response to the Great Depression, revived Wilsonian ideals about the virtues of a freer flow of trade and investment in protecting the health of international capitalism and crafted policies designed to encourage major U.S. trading partners to agree to reciprocally reduce tariff barriers. Significantly, it also sought to promote greater international economic cooperation by securing congressional approval to join the International Labor Organization. At the end of World War II, U.S. policymakers joined with European leaders to create a broad range of new international organizations which bore a strong Wilsonian imprint, ranging from the United Nations, to the International Monetary Fund, to a newly minted International Labor Organization. The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and the newly created World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) at first sought to democratize these new institutions of international governance by demanding a greater role for organized labor within them, but their efforts came to naught.

Wilsonian internationalist principles perhaps enjoyed the zenith of their influence during the early Cold War when both Democratic and Republican presidents staged many CIA interventions and fought wars in an alleged effort to stop the spread of Soviet communism. In justifying such actions, policymakers often conflated democracy and capitalism in a manner reminiscent of Wilson. Free markets, they argued, led to freer and more democratic forms of government. Yet critics charged that many U.S. Cold War allies seemed more dedicated to suppressing rather than strengthening democratic institutions despite their embrace of capitalism. To a striking degree, the AFL-CIO leadership assisted U.S. leaders in their battles against foreign governments and labor movements that pursued socialist, communist or economically nationalist policies that hindered capitalist economic integration and U.S. corporate expansion. Examples ranged from AFL and CIO interventionism in the Japanese, Latin American and European labor movements to undermine leftist tendencies following World War II, to the strong support of AFL-CIO leaders for the U.S. war in Vietnam, to U.S. labor complicity in CIA plots against democratically elected Socialist leaders such as Jacob Arbenz Guzman in Guatemala and Salvador Allende in Chile.

During the early years of the Cold War, opposition to such policies among the rank and file of the U.S. labor movement remained relatively weak, since many left-leaning unions within the AFL and the CIO were expelled after the passage of the Taft-Hartley act. Yet during the Vietnam War, new coalitions of labor activists critical of both the U.S. government’s and the AFL-CIO leadership’s Cold War foreign policies developed. Many also began to question whether free trade and unrestricted capitalist mobility always served the interests of the world’s workers. Critics gained new influence at Cold War’s end when the AFL-CIO revamped their international affairs programs and lobbied against the North American Free Trade agreement. Dissent within the AFL-CIO seemed to have come full circle when activists created the group U.S. Labor Against the War to oppose the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. Reminiscent of World War I era labor dissidents, this group claimed that U.S. foreign policy toward Iraq was guided not by a commitment to make it safe for democracy but by a desire to make it a haven for corporate greed. More broadly, U.S LAW has committed itself to ending U.S. “dependency on militarism so that it can develop an environmentally, economically and socially sustainable and just economy that serves the whole country, not just the privileged few.”

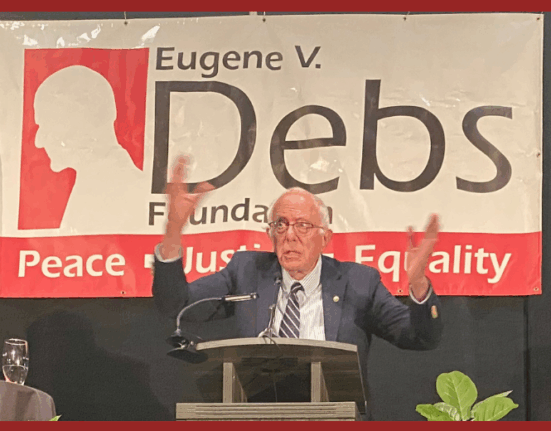

If groups like U.S. LAW have dedicated themselves to long-term structural change as a prerequisite to redirecting U.S. foreign policy, the recent election of Donald Trump seemed to signal a willingness by some working-class voters to make a Faustian deal with the devil comparable to that of 1920 in order to defeat the expansive Wilsonian internationalist vision that has dominated U.S. diplomacy for much of the past century. Yet the far right turn in the Republican Party makes this an even more troubling development than in 1920. Needed is a serious third party alternative that will reject the capitalist-driven international visions of both Neo-Wilsonians and Neo-Conservatives and make working-class needs the centerpiece of its agenda. Labor and Socialist dissident groups, from World War I to the Bernie Sanders coalition, offer important insights for beginning this task.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.