Love and Solidarity, a new film directed by Mike Honey and co-produced with film maker Errol Webber. Non-violence is not passive, but is militant and effective theory and practice. Portside Moderator Will Jones interviews Honey about the film and highly respected, long time religious leader, organizer, and educator James Lawson.

Will Jones: Why this film now?

Mike Honey: James Lawson’s theory and practice, ranging from the early civil rights and anti-war movements until now, offers us on the left, in the streets, a long term view based on his experience of teaching and organizing since the 1950s. He never claims to have all of the answers but provides a framework that challenges us to not just protest but to transform situations and systems, to build coalitions, to win people over to sanity. The Black Lives Matter movement’s evolution from impressive protests in Ferguson and elsewhere to a platform and call for continued action is an example of both the power and challenges faced by us here in USA and globally.

We deliberately made the film relatively short, 38 minutes long. It is effective for classroom use, union meetings, on campus, in community meetings. The intent is to start a conversation. Different strands of the left – Latino/a rights, immigrant rights, labor rights, civil rights organizing, social justice speak to just about any audience. Most people who see the film will never have heard about Jim Lawson. This is not an in-depth biography, but rather an introduction to Lawson and the theory and practice of non-violence. We hope it opens up questions of effective theory and practice for all activists.

WJ: So what does the film cover?

MH: Love and Solidarity takes you through Lawson’s early life and into the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 60s and then into the economic justice, immigrant rights and Dreamers student movements in Los Angeles – in all of which Jim Lawson participated. Rather than a biography of Lawson we wanted to try to capture how the ideas and practices that he’s been teaching and doing as an organizer through the years remain powerfully relevant today. The idea for the film started with Kent Wong at UCLA Labor Center. Unions are being crushed and destroyed in most places in the USA, but in Los Angeles the labor movement has grown in strength. This was partly through transformational leadership from organizers inspired by Lawson. In 1980-90s one of the first Latina union leader in Los Angeles was elected, Maria Elena Durazo (HERE Local 11). She and Wong both relate in the film how they both learned from Lawson the theory and practice of non-violent action applied to labor movement

WJ: Can you talk about Jim Lawson’s early life and formative experiences?

MH: He was born in 1928 into a family with deep roots in the black freedom struggle and the Methodist church. His great-grandfather had escaped slavery in Maryland in the 1840s after struggling with and killing a slave catcher and fleeing to Canada. The Lawson family prospered for several generations in rural Ontario, until his father moved the family to the U.S. at the end of World War I. Jim was born in 1928 in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, and spent his formative childhood years in Masselon, Ohio, a steel town. As a Methodist minister, his father traveled the circuit and the family moved a lot.

Lawson’s father was a strong advocate for freedom and civil rights and often carried a gun. Remember that in the Midwest there were and still are lots of areas just like the South. Lawson’s family was large with 11 children. After his father’s first wife died, Lawson’s father married an immigrant woman from Jamaica with whom he had a second family, which included Jim.

Jim tells a story about a kind of epiphany around 4th grade, at a time when his father was teaching him to fight, to stand up for himself. A white child called him the n…word. Jim slapped the white kid and told the kid to never say that again. Jim got home proud to tell his parents about how he was militant. Jim’s mother asked, “Jimmy, what good did that do? ” From that time forward, according to Jim, he resolved to never use physical force to defeat racism but to use his mind instead. Ultimately, the study of nonviolence gave him a method to deal with not only individuals but systems of power. At an early age Lawson had a remarkable sense of self and deep belief system.

Lawson took that epiphany with him to college, studying Gandhi, Thoreau and others. He met A.J. Muste, a great non-violence advocate who had also been an important labor organizer in the 1920s and 30s. Muste became a big influence on Lawson. Lawson went to seminary and was ordained by the time he was 18 years old, so he got a ministerial deferment from service during the Korean War. He didn’t have to worry about the draft, but he still turned in his draft card because he thought the draft was an instrument of war and also oppressive of people. Lawson went to prison for this draft resistance even though he could have used a religious deferment. The film does not cover this detail – there’s not enough time to share all of Lawson’s impressive life.

Lawson was released early from prison to do missionary work for his Methodist church in India where he taught sports and continued his study of Gandhi. When he returned to the USA he went to Oberlin College, where he met Martin Luther King, Jr. shortly after the bus boycott in Montgomery – King realizes here is someone who deeply understands non-violent theory and asked Lawson to move down South to help build a nonviolent movement against segregation. Lawson, [Bayard ] Rustin and others became part of a young generation of people of pacifism and non-violent action contributing to the larger left in the United States. An interesting thing about this is he did not agree with the word “pacifism”. Lawson did not think there was anything passive about non-violence. He wanted direct action. He saw non-violence as a militant form of resistance to not just racism and segregation but to all the evils of the world. In his view, this included poverty and racism, and all forms of systemic violence.

Lawson moved to Nashville as a southern field organizer for the Fellowship of Reconciliation, which had been founded by A.J. Muste and others during World War I. Jim was one of the youngest non-violence organizers (in his mid-20s) as he traveled all around the South working in Little Rock and Virginia. Lawson is well known within this historical movement, but not among the general public. This is because he saw himself as a teacher and organizer, not as a leader. An example is that he was chosen to give the keynote speech at founding of SNCC. People knew enough about him that they wanted to hear what he said, how he organized. He helped to launch a generation of nonviolent revolutionaries.

WJ: After Nashville, did Lawson become a mentor to Diane Nash, John Lewis and others?

MH: Yes, I think you can say that. Many of those folks became leaders of what King called the “model movement in Nashville” because that Nashville campaign and organizing was so effective and successful. Before the action of Nashville began, the participants spent well over a year studying and planning before launching sit-ins. Those sit-ins were part of the birthing of SNCC.

WJ: Was Lawson involved in the Freedom Rides?

MH: After the initial vicious, violent attacks against the Freedom Riders there was real debate and fear that the effort would not continue. Nashville’s Diane Nash and others in the Nashville movement made sure to get back on the bus and keep the rides going. Jim ended up in infamous Parchman prison along with other Freedom riders.

WJ: What other work did Lawson do in the South?

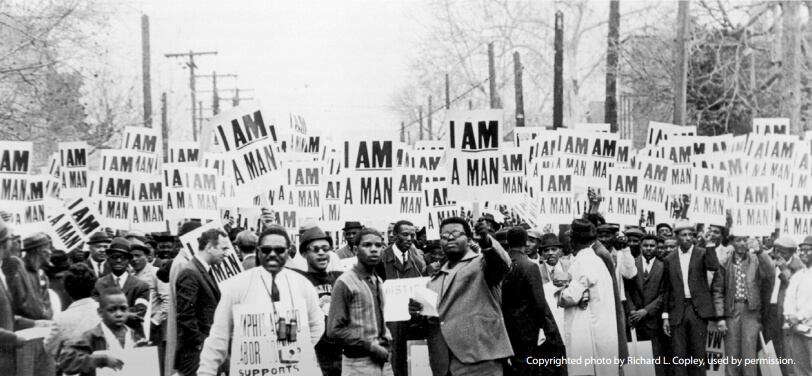

MH: Mostly Lawson taught annual sessions about non-violence theory and acted as an advisor to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). King wanted to hire Lawson as SCLC staff, but Lawson made strong critical remarks about the NAACP in his famous SNCC speech so the NAACP pressured King to not hire him. While teaching non-violence and advising SCLC, Lawson was a minister at a small Methodist church in Shelby, a small town south of Nashville. Later Lawson moved to Memphis where he was pastor at the old, established Black church, Centenary United Methodist. The 1966 March Against Fear with James Meredith came through Memphis with Lawson’s crucial help and participation. The famous Memphis Sanitation Strike was a campaign where Lawson’s role as organizer expanded . Initial police violence against the strikers lead to a large meeting of more than 150 ministers – who elected Lawson as the campaign’s ministerial leader. The 6 week campaign was intense – it was Lawson who invited King to participate. They had been working closely together, and in 1965 Lawson had gone to Vietnam in place of King who could not attend.

Lawson was consistently anti-war and anti-capitalism, one of the few left religious organizers and theorists of revolutionary social change. As I wrote in my book Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign, Lawson believes that a person of non-violence is a person who wants systemic change. Everything that oppresses people demands an organized campaign to win change. For Lawson this non-violence is a spiritual practice, not a tactic. With such an approach, Lawson feels you then know better how to effectively utilize the theory and practice of non-violence.

WJ: So explain more how Lawson characterizes non-violence?

MH: At a series of talks we utilize in the film, Lawson outlines the four steps of non-violence. Basically he talks about an organizing strategy. First phase is when you have to research, talk together collectively and figure out then what can you do. Second step is confrontation – going to the powers-that-be with your demands. Step 3 is a mass campaign of disruption. So with Jim Crow, the movement made it impossible for that system to function. Downtown Birmingham ceased to function! There were not just marches but also economic boycotts and other actions. Finally there is the step of negotiation and reaching settlement or agreement. The strategy is to transform the situation and in a spiritual sense try to turn your enemies around. I’m impressed when at the end of the film Lawson talks about means and ends being the same thing. You can‘t control the results of your actions but you can control your actions. You can try to do things in the right way, that is you decide this is the way I want to be and to act. You work with other people in a disciplined way to achieve both the process and the result.

WJ: Often people think of non-violence as allowing something to be done to you. Lawson doesn’t say that, does he?

MH: Non-violence is not passive but instead is very active, disruptive and an intervention into a situation where you are saying no more cooperation with the situation. Non-violence is militant. When Lawson moved to Los Angeles as a minister at Holman UMC he continued what he calls “experiments of truth” in this bigger church and in a much larger city. The experiment is how do you move things – life is an experiment to move things forward.

At this point, in the 1980s, the labor movement in Los Angeles was stymied about how to organize hotel workers. Using the usual union tactics resulted in loss of members and power. The Hotel and Restaurant union brought in Lawson and Caesar Chavez to talk about non-violent action and coalition building with allies. If your analysis of the issues is correct, you can find allies outside of your sector, winning over people who are skeptical or against you. Then, at some point if necessary, you can disrupt and move forward through nonviolent direct action. How do you do it? What spirit motivates you and others? His teaching and experience are that you try to win people over in part by your demeanor and how you deliver the message as well as what the message is. You create openings for people to support you. He defines violence not as property destruction, but destruction of people. Lawson’s non-violence is against violence to any living being. If you’re doing violence to another person you might defeat them, but you are not winning them over. You have not transformed them. Lawson’s spiritual approach includes not using or collecting bad karma defining use of any violence as also violence to yourself. He is not naïve. You can’t always win over your opponents. But you might win enough allies to transform the situation and build the basis for a better future.

WJ: Can you say more about Los Angeles at this time? What was happening in labor movement?

MH: Remember I am not an expert on Los Angeles, but my understanding is that this was a critical moment with growing tensions between the Latino immigrants and African-American communities and workers.

Lawson arrived in Los Angeles in 1974 with lots of responsibilities and work at Holman UCM. He still continued with lots of presentations and teaching about non-violence and was also traveling in response to requests for his teaching. Lawson always made time for direct participation in Central American solidarity work, anti-nukes and anti-war and social justice issues. Lawson often says he has been arrested more times in Los Angeles than he was in the South.

I In the 1980s the hotel industry successfully busted the unions by laying off African American workers and replacing them with Latino immigrant workers. Utilizing teaching and advice from Lawson and others, innovative leaders like Maria Elena Durazo were able to re-unionize the hotel industry and build a powerful worker movement over many years of hard work. That included doing your analysis, organizing your base, confronting the powers that be, building alliances — nonviolent direct action, in that context, worked.

WJ: Was this also the time of Justice for Janitors?

MH: Again, I’m no LA expert, but the hotel workers and janitors organizing were two separate campaigns in industries where employers were using many of the same anti-worker and union techniques of divide-and-conquer along ethnic lines. Union leaders who were open to “new” strategies like those Lawson was teaching were able to turn around the union decline and re-build in the 1980s-90s in LA. Those successes then led to organizing new sectors like security guards. Unions began to recognize and organize the new Latino and immigrant population in LA. The film shows how Lawson’s role as teacher helped union leaders effectively build coalitions. The film also shows the exciting connection with the Dream Act students seeking a path to citizenship, and current movements among students and workers as well as Kent Wong’s impressive work at the UCLA Labor Center.

Although retired from his ministry at Holman UMC, Lawson still is actively teaching and traveling and speaking about non-violence. He has not done a lot of published writing, but the internet is a good source to understand his thinking and his work. There now is a Lawson archive and endowed faculty position at Vanderbilt University– they regret expelling him for his leadership as a Vanderbilt student during the sit-in movement of his younger days. You can find a lot about Rev. Lawson and the film at, loveandsolidarity.com

BJ: Do give us the details of the film’s distribution and availability.

MH: Bullfrog Films is our distributor. For ordering info go to BullfrogFilms.com. There are special discounted rates for rental and purchase so that unions and community groups can afford to use the film to support organizing. As I said the 38 minute film is short enough to be used in classrooms, at union or community meetings or other venues. The length allows time for discussion and sharing. We also encourage folks to get your local public or campus library to order the film to increase accessibility and use. We have found the film to be an effective and great conversation starter. The film touches – as does Lawson’s work – many different strands – Latino/a rights, immigrant rights, labor rights, civil rights organizing, social justice. Pretty much any audience will pick up on current concerns. Most people who see the film have never heard of Jim Lawson, so it’s impressive to see people question, “How come I never learned this?” The film is not meant to be an in depth biography or lesson about non-violence. The film, like Lawson, opens up questions and challenges us with ideas so we can move forward.

BJ: Any final thoughts to share with portside readers?

MH: I hope this film will be useful to people today. Rev. Lawson urges us to confront all forms of violence at the individual and systemic level, to confront racism, sexism, poverty, labor exploitation and injustice. The message is that we must protest, but beyond protest, organize for systemic change. He urges us to study nonviolence as a strategy, practice, and philosophy. It is not the only answer to the world’s problems, but Rev. Lawson has shown that it can transform individuals and society. How do we build upon the legacy of our freedom movements? I hope that these are some of the questions that people will take up when they see the film.

In addition, the book Nonviolence and Social Movements: The Teachings of Rev. James M. Lawson Jr. is the first book that captures James Lawson’s teachings. Five powerful case studies explore how individual acts of conscience can lead to collective action and how the practice of nonviolence can build a powerful movement for social change.

This post was originally posted August 12, 2016 on Portside. It has been reposted with permission from the authors.