In 1968, on the corner of the campus of Indiana State University, there sat a small home. Previously a member of Terre Haute’s older downtown suburb, time and the university’s expansion had witnessed the neighborhood go from row upon row of upper class homes, to areas annexed for the college’s use. The home in question, located at 451 North 8th Street, was one of few remaining survivors of the old neighborhood. It was also in the path of the University’s dreams for development. In its place the University planned a new parking lot to service the “state of the art” Statesmen Towers. When completed, these twin towers were to be affordable residences for students, a sign of the college’s progress, and potential landmarks as the fifteen story buildings would rise above the small town.

Just a few years earlier, the University would have had little problem removing the obstructing home. In 1936 the original owner, a childless widow, died. A faculty member of the college then bought the house, and lived in it for a number of years before selling it to a fraternity in 1948. Once in the possession of Tau Sigma Alpha, the home accrued the damage one would expect a college fraternity to inflict until, in 1961, it was sold again to a developer. If left to its own decline, the home would have likely continued its deterioration until the University rendezvoused with the structure, via wrecking ball, in the last years of the 1960s.

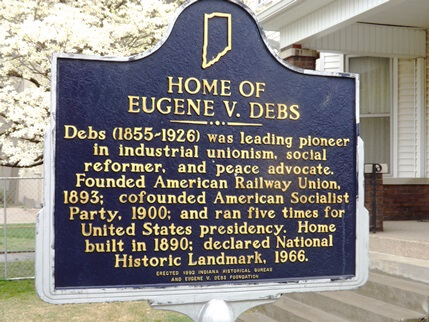

Fortunately, this did not happen. In 1962 a group of dedicated academics, labor activists, and community members came together and purchased the home for the grand total of $9,500. Why did this happen? Why would such normally disparate groups come together to buy a home? The answer was simple. For nearly fifty years, from it construction in the late 19th century to the 1930s, the home belonged to the family of Eugene Victor Debs. A five-time candidate for the Presidency of the United States, a widely known labor leader, and a world renowned orator, Debs was one of the most famous socialist politician ever produced by the United States.

Born in Terre Haute in 1855, Debs attended school until the age of fourteen before dropping out and joining the Brotherhood of Locomotive Fireman. A young man with political ambitions, he eventually served two terms as city clerk and one term as a Democratic representative to the Indiana General Assembly. Yet, after his term ended in 1889 he turned away from electoral politics and dedicated his work to labor organizing. He did, however, marry during his time in the Assembly, and in 1890 finished construction of the home. Large and elegant for its times, the home reflected the status of a rising political star. His new wife, Kate Metzel, was of upper class stock, and believed she had married into potential political royalty. She would soon be disappointed.

In 1893 Debs organized one of the first US industrial unions in the form of the American Railway Union (ARU), and made quick work of empowering previously ignored unskilled laborers. The ARU just two years later backed striking car construction workers of the Pullman Company.

The Cleveland Administration, hostile to the workers, used federal troops and legal maneuverings to crush the strike. On June 20, 1894, citing a court injunction, the Administration claimed the strike disrupted the flow of mail, and therefore posed a national security risk. The injunction also targetted anyone verbally supporting or inciting the strike. Dozens were either killed or injured in the resulting battles. Debs, for his leadership and outspoken support, was arrested, tried, and sentenced to prison. It would not be the last time his democratic rights landed him in trouble with the law. He famously claimed that the time in prison resulted in his decision to connect labor issues with a quest for socialism.

In 1918, with the eve of US involvement in WWI approaching, Debs gave a speech in Canton, Ohio where he spoke out against US entry into the war. Arrested, and tried for treason, Debs offered a passionate plea for social justice in his legal defense. Despite his appeal, the court sentenced Debs to ten years in prison. Pardoned by Warren G. Harding in 1921, Debs passed away in 1926. He was buried in Terre Haute, not far from the home he rarely stayed in during his life. As the orderly processes of collective bargaining were secured in the mid-twentieth century, few remembered the vibrant battles for social justice that had motivated Debs and his cohorts. One of the few groups who did was the Debs Foundation, who were determined to keep the history alive for future generations.

Following the purchasing of the home, the Foundation decided that the best way to honor Debs’ memory was by turning the home into a museum. With the financial support of local chapters of the AFL-CIO and the UAW, much of the damage caused by old age and the home’s fraternity years was quickly fixed.. As Bob Constantine, a member of the Foundation and historian, remembered years later, “By 1967, the ‘remarkable progress’ … included the near completion of the physical restoration of the Debs home…and the beginnings of the Foundation’s work in the fields of education and research.”

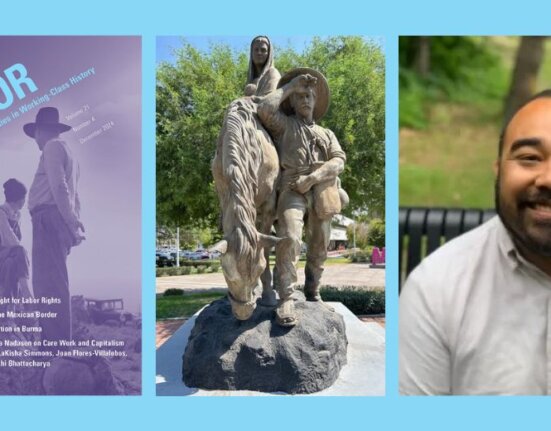

Aside from maintaining the home as a museum, the Foundation also contributed to the advancement of Debs in public memory through education. This included working with Indiana State University library to establish and maintain the Debs collection, the largest deposit of Debs papers in the country. It also included awarding an annual “Debs Award” given every year to a figure “whose work has been in the spirit of Debs and who has contributed to the advancement of the causes of industrial unionism, social justice, or world peace.”

The house was preserved enough by 1966 that it was made a National Landmark by the National Parks system. This protected the property from dangers such as seizure through eminent domain. Two years later the demarcation proved to be a powerful designation, as the University developed the property around the home. Finding that the house was not able to be torn down, University officials offered to move the home to a location further away as to make room for the development. The Foundation refused. As a result, the home still sits at its 1890 location where Debs had it completed.

In 2013, a new peril to the Debs House arose when Indiana State University announced the nearby Statesmen Towers would be demolished. Although in the 1960s the University billed the towers as “state of the art,” they were now labelled architecturally unstable. Although the University offered to construct a “barrier and netting or cover to protect the entire museum site from flying debris,” several Foundation members opposed the idea, citing the risk the demolition posed to the historic site.

In 2014, the University temporarily halted plans to demolish the towers, opting to explore the possible refurbishing of the buildings for continued use. Yet in April of 2015 the University went ahead with demolition. At 11:00 a 7,000 pound wrecking ball slammed into the towers’ east building sending debris crashing down. Initially skeptical of the demolition, the Foundation was at least placated that the University were not imploding the buildings.

We might reflect on the University’s demolition of an unstable high-rise that overshadowed the Debs home. The need to preserve the spaces of history in our midst competes relentlessly with capital’s quest for erasure of memory and unlimited growth. The existence of the Debs home stands in contrast to the marketing of the university, which now seems to relentlessly reflect the political economy of capitalism and the erasure of the mission of universities. The centenarian Debs house, stands strong though community engagement while the towers were abandoned in a mission of growth for growth’s sake. It is an irony that Debs himself would have appreciated.

Sources:

Debs Foundation News Letter, Fall 1989, “The Debs Home:100 Years of History,” pg. 3.

Debs Foundation News Letter, Fall 1992, “Twenty Five Years Ago the Debs Foundation: 1967,” pg. 3.

Debs Foundation, website, accessed 3.12.15 http://debsfoundation.org/foundation.html

Sue Loughlin, “Days are numbered: ISU asking for towers demolition money,” Terre Haute Tribune Star, February 15, 2013.

Sue Loughlin, “Debs home to be safe during towers’ demolition, all parties say,” Terre Haute Tribune Star, January 29, 2015

1 Comment

Comments are closed.