I am a historian who studied with David Montgomery at the University of Pittsburgh in the mid-1970s, a tumultuous time in labor and working-class history. After teaching at Wesleyan University for many years, I returned to the once-mighty steel city.

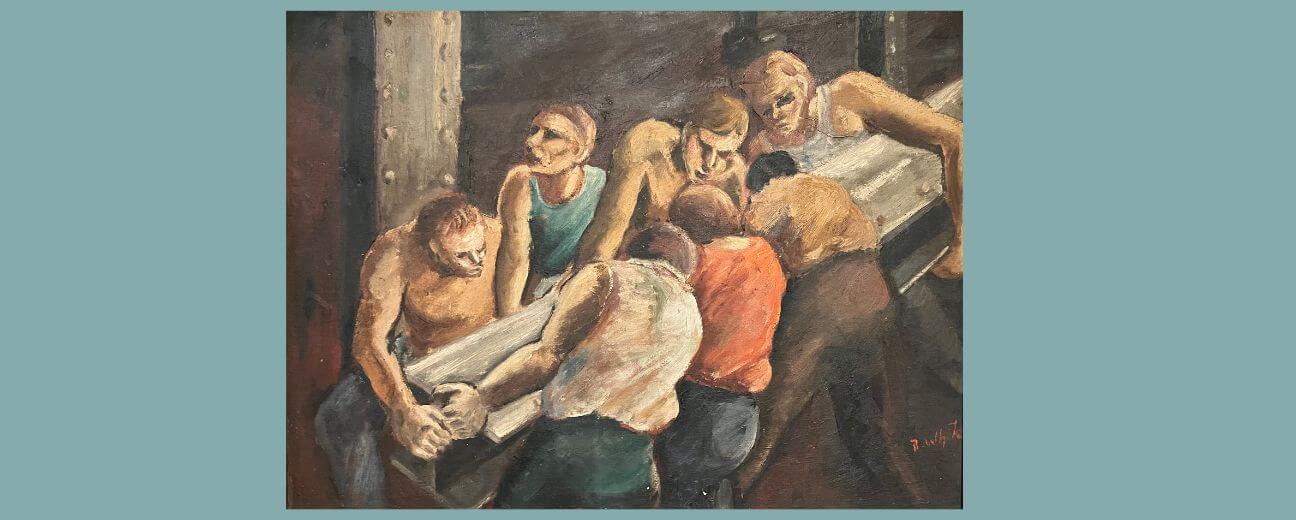

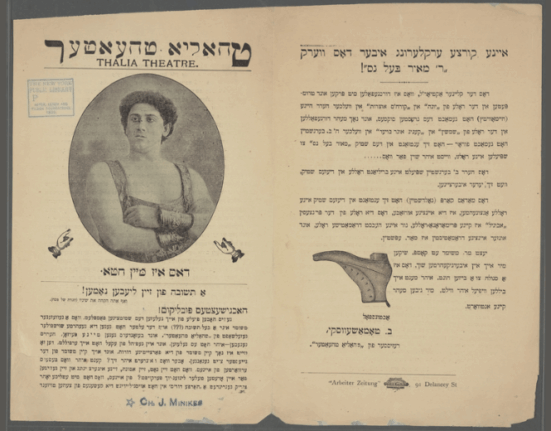

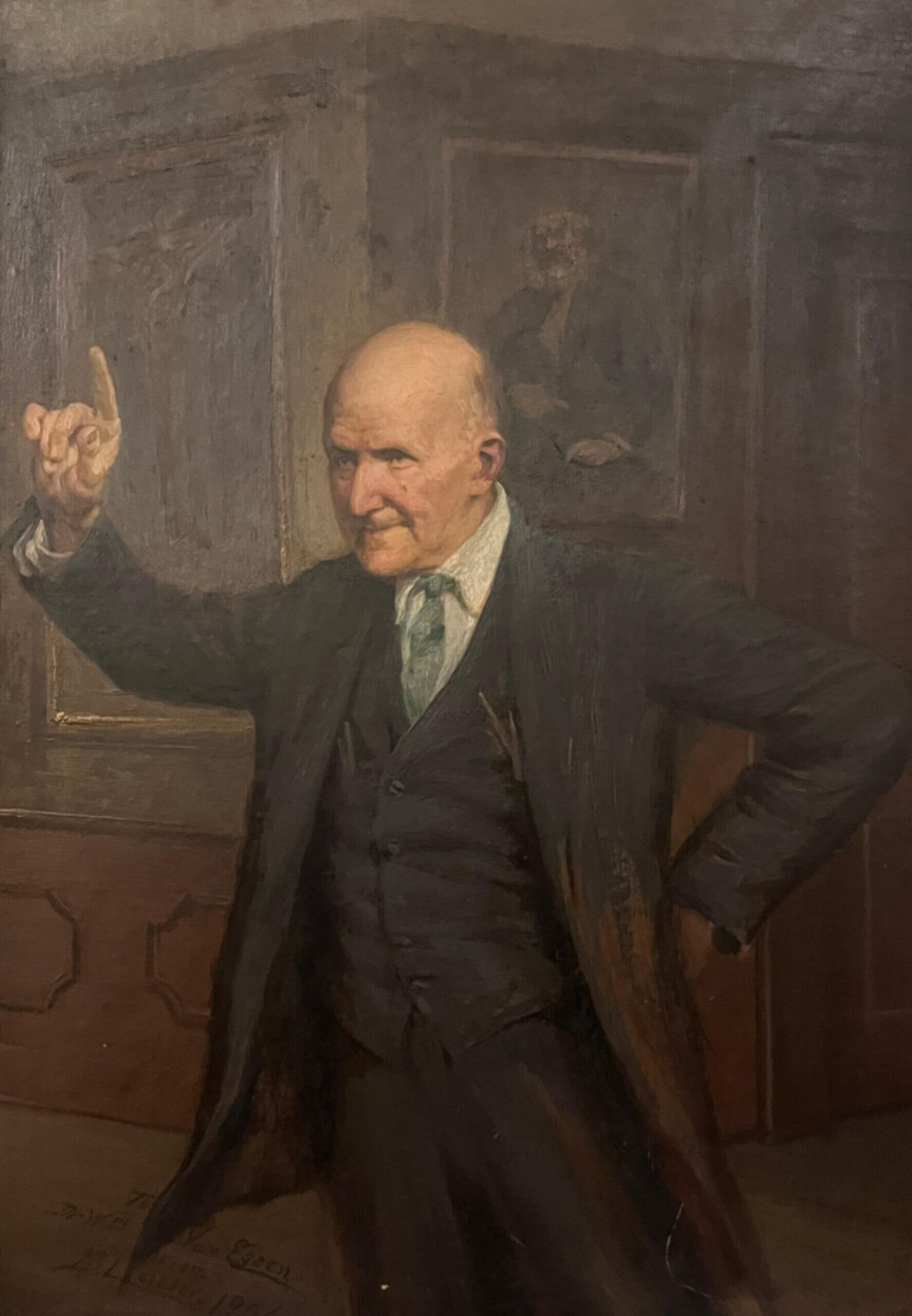

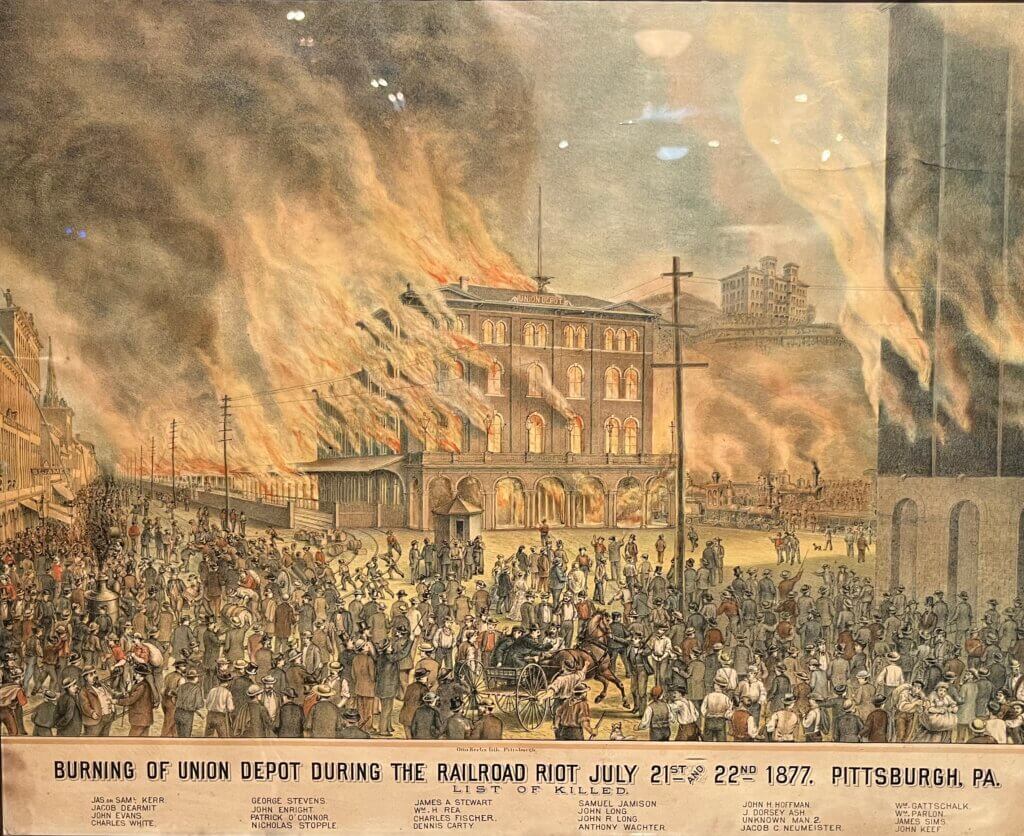

I recently saw a remarkable exhibit entitled “Labor & Art” in nearby Homestead, Pennsylvania. Fifty compelling paintings, sculptures, posters and prints depicting union and worker militancy mainly in and around Pittsburgh from the 1877 railroad strike through Ed Sadlowski’s campaign for the Steelworkers’ presidency in 1977 make up the display. Coal miners, railroad workers, and steelworkers are highlighted.

The exhibit was largely put together by Joe White, who taught English working-class history at Pitt, and his wife Delsa White. Joe and Delsa spent weekends for years at old bookstores, yard sales, and antique shops seeking material on Western Pennsylvania workers and protests. They installed their many finds in their house in Harmony, Pennsylvania, a former utopian community founded in 1804. Harmony was the first of three communities built by the Harmony Society.

The artwork that they amassed (along with that of several of their friends), is now on display at the historic Bost Building in Homestead. Originally a hotel, the Bost Building served as headquarters for the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers during their famous armed battle with the Carnegie Steel Company in the summer and fall of 1892. Using the third floor as a watchtower, the union officials monitored activities in the mill site and along the Monongahela River. The hotel also served as the base for American and British newspaper correspondents who filed their stories about the Homestead strike and the battle.

The same third floor now houses the Whites’ Labor & Art exhibit. I would encourage everyone on the Labor and Working-Class History Association list near Pittsburgh to see the exhibit. It will be on display until December 23rd. The Bost Building’s address is 623 East 8th Avenue, Homestead, Pennsylvania. It is normally open on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday 10 AM – 2pm and by appointment. Their telephone number is 412-464-4020. The website is linked here.

There is parking behind the building. Admission is free. When you arrive, go to the front door and press the button on the left side to be admitted.

While there, also be sure to walk through the Rivers of Steel exhibit on the first floor of the building. Rivers of Steel is a federally designated National Heritage Area in southwestern Pennsylvania, centered on Pittsburgh and oriented around the interpretation and promotion of the region’s steel-making heritage.

After seeing the exhibit, I sat down for an interview with Joe and Delsa White.

How did you become excited about Western Pennsylvania labor history?

Our interest in labor art began when we were children. Both of us grew up in houses with art in almost every room. A second factor was political. Our parents were far to the left of center, something we became aware of as kids in the early 1950s. It was in Pittsburgh that our interest in art and labor came together. Neither of us are native Pittsburghers. This stimulated our curiosity to learn more about artistic and artisanal representations of workers in the area. And we did learn from looking at those artworks and objects.

Do you view this art as a primary source like a document?

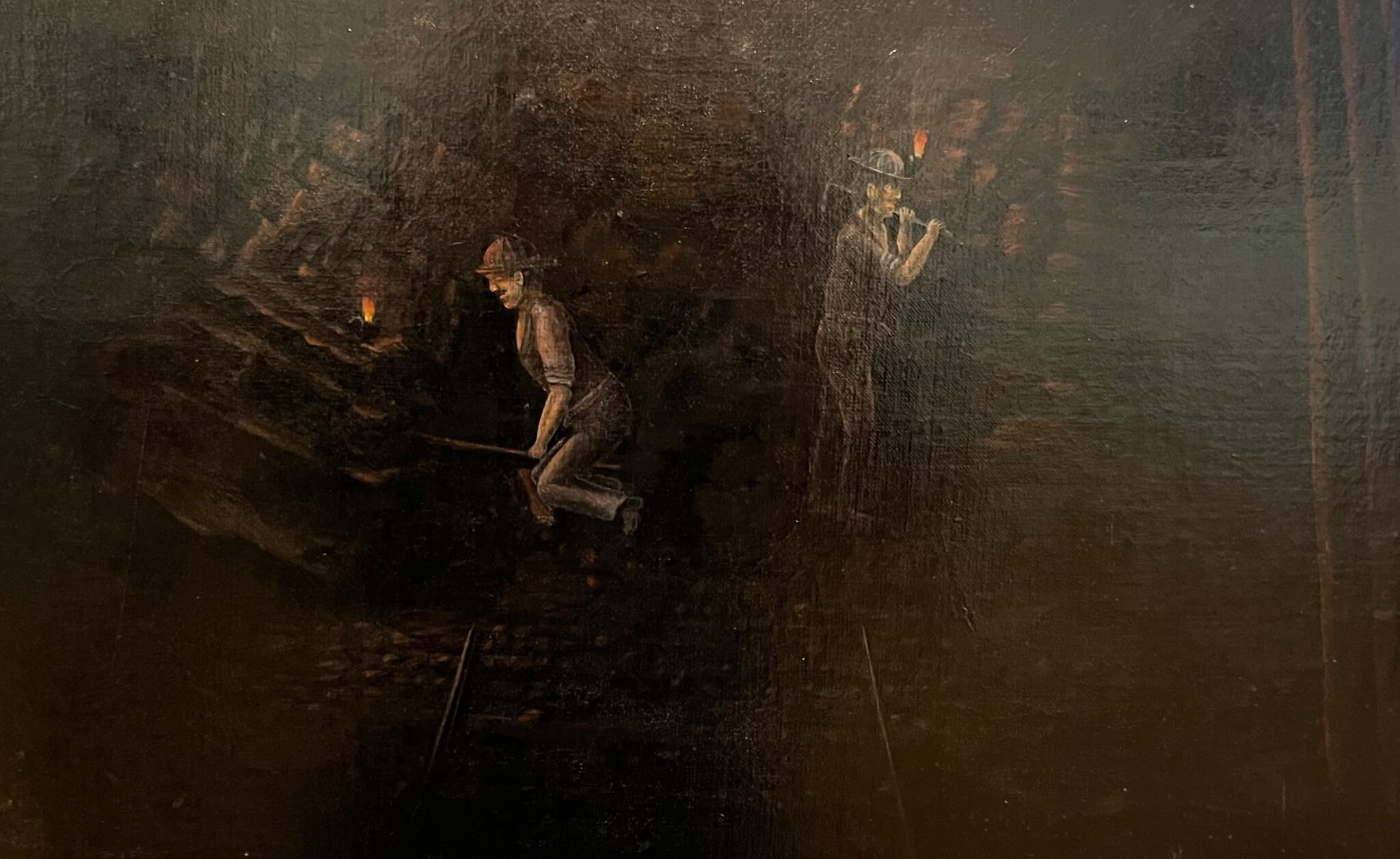

Consider the painting “Miner’s Portrait.” One of its many remarkable features is that management is nowhere to be seen. This is a bit strange, to say the least, given the bosses’ obsession with keeping a close eye on workers. Was the artist purposely ignoring the bosses? David Montgomery’s answer is a resounding “No.” In fact, just as the painting shows, miners’ independence was the envy of other workers.

Were you startled by what you saw in those works of art?

Some cliches contain a kernel of truth. “A picture is worth a thousand words” is one example. We don’t know any writing that matches, much less exceeds, “Burning of Union Station” or “Haymarket Riot” in conveying the emotion and motivations of those workers. “Things Were Better Then” is a more subtle but equally powerful statement of loss and destruction.

How does the artwork in your exhibit compare to that found in major art museums?

Except for the famed Pittsburgh Courier photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris’s photos of African Americans and John Kane’s paintings, the permanent collection at the Carnegie Museum of Pittsburgh has relatively little art by or about working people. The Frick Pittsburgh Museum has even less. That is true of many major museums in the United States. But working-class people are already or soon will become the majority of humankind. Artists of all media will continue to take notice!

Author

-

Ron Schatz is Professor Emeritus of History at Wesleyan University. He is the author of The Electrical Workers: A History of Labor at General Electric and Westinghouse, 1923-60 (1983), The Labor Board Crew: Remaking Worker-Employer Relations from Pearl Harbor to the Reagan Era (2021), and many articles, including “The Barons of Middletown and the Decline of the Northeastern Anglo-Protestant Elite,” which was published in Past & Present in 2013.