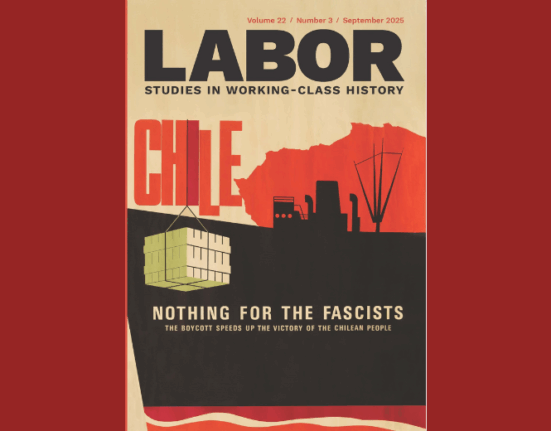

The new issue of of Labor is now available. The entire Up For Debate forum section of the issue will be available for free until January 26, 2026. The topic of the forum is “The Wages Of War: Debating Military and Labor History.” . We begin with the provocation that begins the forum, Class/War: Do Labor and Military History Work Together? by Justin Jackson. In coming weeks Labor Online will feature comments from the other scholars who joined the forum as well: John Hall, Tej Nagaraja and Reena N. Goldthree.

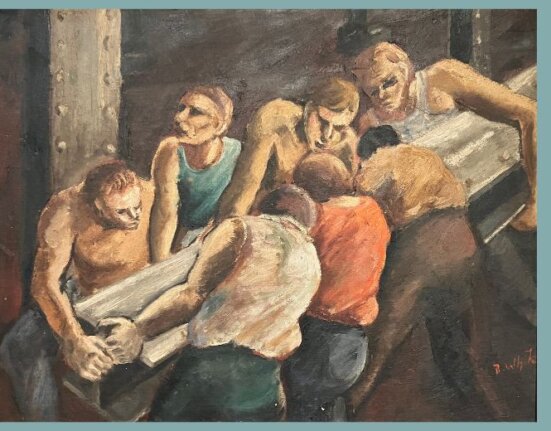

The specter of war haunts American labor history. President Donald Trump’s recent deployment of National Guard troops to Democratic-led states, all to bolster his administration’s aggressive deportations of immigrant workers, might remind us that “war” is more than just a metaphor for labor and its complex past. Of course, employers, workers, and their allies and observers have often described the spectacular but episodic violence of American labor relations in martial terms. The Great Strike of 1877, the eight-hour movement and riot at Chicago’s Haymarket Square in May 1886, clashes at Andrew Carnegie’s steel mill in Homestead, Pennsylvania, in 1892, West Virginia’s “Mine Wars”–were all compared to warfare by contemporaries, and historians since. The sociology of industrial life has resembled the sociology of military life (and, perhaps, death); the regimentation, hierarchy, and discipline of modern production seem to imitate that of martial organizations, as disposable labor is exceeded only by disposable soldiers. And of course, American radicals have long described political tensions between labor and capital as if it represented a kind of warfare. The preamble of the Industrial Workers of the World described capitalism as a continuous class “struggle” between working people (“the army of production”) and “the employing class”–one in which “peace” became possible only by abolishing wage labor itself.

Yet historical intersections between work and war remain a relatively under-investigated field in labor history. To be sure, social and global historians recognize that war and violence, whether public or private, brought about a modern capitalism which economic and political philosophers idealized as an inherently pacifying force. Students of American class formation in the early republic and antebellum era acknowledge that the political and military mobilization of colonists for revolution against Great Britain both reduced class barriers to political participation for white men, and left among its many legacies a nationalist discourse of equal rights for rich and poor. Certainly, many historians recognize that civil war yielded the greatest victory labor ever won in American history: the liberation of nearly four million enslaved men, women, and children from bondage. Still, and paradoxically, the same social theory that invites us to compare the exploitation of labor under capitalism to warfare also produced a politics that demands workers reject war as a violation of internationalist principles. Working people, we are to believe, have no country; their loyalty extends only to those in their own class, not the nation at large.

Such a priori assumptions inevitably encourage errors of historical interpretation, argument, and emphasis. What struck me after 2001, as a young student of labor history amid the War on Terror, was how few Americans, working class or otherwise, identified with the poor in Afghanistan and Iraq whose countries the United States was invading and occupying (often with troops from poor and working-class backgrounds). Workers, I realized, were just like everyone else: they have multiple social identities and interests that shift over time and rarely may be reduced to a single and exclusive category, such as class. Yet historicist theories of class politics that presume workers will or should become more internationalist over time seem to offer little more than “false consciousness” or cultural “hegemony” as explanations for why American workers “failed” to become properly internationalist. One result is a literature on organized labor’s foreign policy in the twentieth century, informed by concepts of “corporatism,” “corporate liberalism,” and “social imperialism,” which suggests that American unions’ desire to maintain political influence and living standards halted their march toward solidarity. Such research, however, seemed to locate the co-generation of war, capitalism, and class solely in domestic and international political economy and politics, not actual warfare itself.

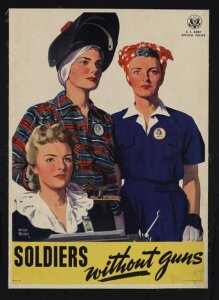

Investigative reporting into the substantial army of Filipinos and other “third country nationals,” employed by defense contractors to meet the everyday needs of the United States’ sprawling empire of bases, in the Middle East and beyond, pointed me elsewhere. So did new studies of “military labor,” written mostly by European and American scholars, which have tended to focus on the work of soldiers. To research the history of the politics of non-combatant labor in American warfare, and explore US imperial formation as a labor process, I turned to the history of US invasions and occupations in the Philippines, and Cuba at the beginning of the twentieth century. The work of guides, interpreters, road-builders, porters, Chinese manual laborers, and prostitutes which I discovered appeared to fall outside labor historians’ traditional categories of class, class formation, and class consciousness. Yet this made it all the more fascinating. It also suggested some of the research questions I’ve tried to introduce in this “Up for Debate” feature on “The Wages of War.”

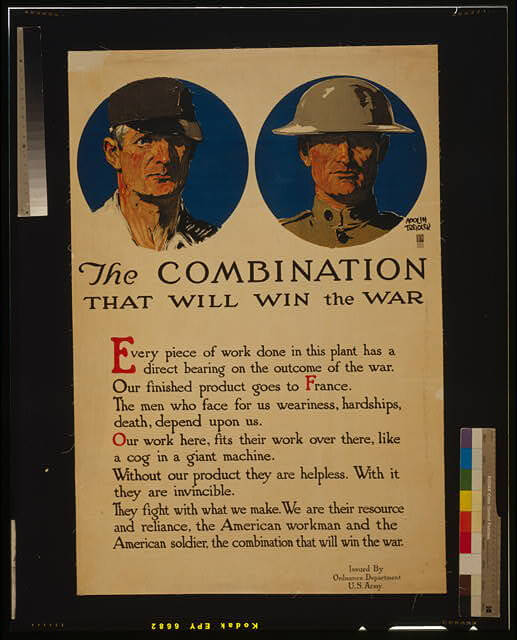

First, I argue, warfare is premised on work; the production of war’s violence is itself a labor process, most evident in soldiering. Second, modern militaries often require secondary armies of non-combatant workers who perform what might be called “the social reproduction of war.” As they reproduced the combat labor (often male) necessary for the economy of violence, these workers generated their own politics, using labor for military institutions to claim pay, security, and status. Lastly, war for workers not only destroys but creates, especially in forming identity and meaning. War often dispenses a material, psychological, and cultural wage to working people who found value in it. This fact may be uncomfortable for some to recognize, and perhaps especially labor scholars committed to working-class internationalism. Yet many poor and working-class Americans have extracted a certain worth from war. Why this is so, and how it has changed over time, is a historical question worth explaining on its own terms.

Such interventions are not intended to defy political convention, nor need they detract from labor historians’ search for a “usable past.” Rather, they might generate scholarship by answering older questions in new ways. What is the historical relationship between war, capitalism, and class? Why do workers come to prioritize “non-economic” interests and identities over their relationship to production and property, and why does that change over time? What encourages working peoples’ “consciousness” of class, or stymies it, under what conditions? Battlefields and bases seem distant from the shopfloors, neighborhoods, union halls, and voting booths that typically attract labor historians. Sadly, they’re not likely to disappear, as sites either of toil and exploitation, or struggle and meaning.

Author

-

Justin Jackson is a Lecturer and Visiting Scholar with the Department of History at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. His book, The Work of Empire: War, Occupation, and the Making of American Colonialism in Cuba and the Philippines, was published this year by the University of North Carolina Press. His article "The Empire of Military Necessity: General Orders 100, Atrocity, and the Law of Occupation between the Civil and Philippine Wars," is forthcoming in the Journal of American History.