This is one of a few brief summaries of panels and papers from the Labor and Working Class History Association conference, June 2025. If you have a comment or summary of a panel or event from LAWCHA2025, send it on so it can be included.

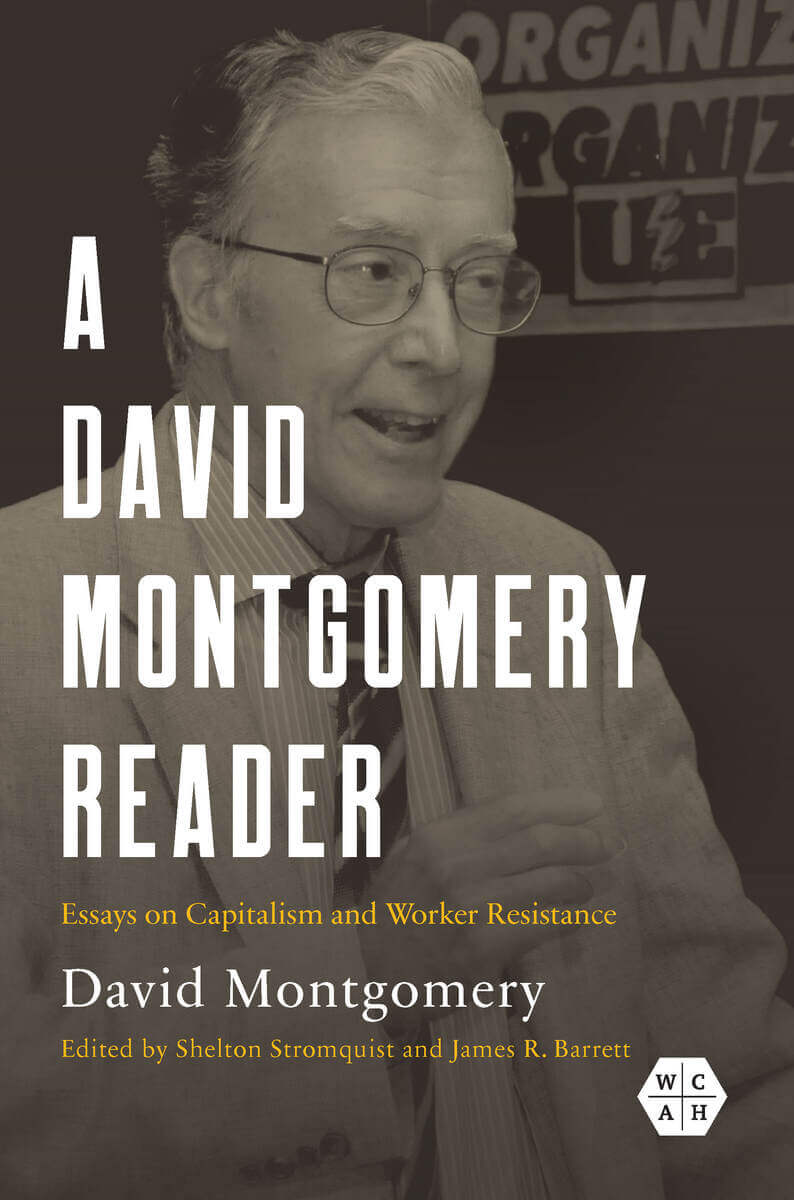

This panel provided much incentive to explore the book of essays that was published last year, A David Montgomery Reader: Essays on Capitalism and Worker Resistance. Both panelists, early students of Montgomery, addressed the question of the continuing relevance of the models, memory, praxis of a founder of the field of labor history.

Shelton Stromquist’s “A Transnational Montgomery” was presented by Lane Windham, as family illness prevented Shel from joining the conference. Stromquist, emeritus professor of history at the University of Iowa and a past president of the Labor and Working-Class History Association, commented on the way that Montgomery has been misread by some as focused on skilled male workers, and prefaced his comments on transnationalism by showing that the collected essays in the book will show that broader shaping of his work. The essays show Montgomery’s attentiveness working-class formation and issues of social solidarity, increasingly more diverse and inclusive in framing these problems.

As is obvious from Shel’s title, his focus for the panel was on the global and transnational approach in Montgomery’s work, and how this approach was initiated, expanded and deepened across the years. Montgomery’s activism in the Communist Party was an important ingredient in the development of this approach as well as his time at Warwick University with E. P. Thompson.

Montgomery’s work was focused on the history of capitalism, and this is also an important reason that Montgomery sought to guide his students to become aware of global contexts for their histories. Workers migration, for example, meant the spread of ideas as they confronted management systems that were also instruments that spread transnationally.

Stromquist highlighted four key themes that emerged from Montgomery’s work: 1) comparative capitalist industrialization, which also relates to investigations of working class formation; 2) cores and periphery, terminology that is associated with world-systems theory but which fueled an intense focus on the recomposition of the working class; 3) imperialism and race as an “integral feature of capitalist transformation and working class mobilization”; 4) labor and the imperial project, with a closer look at workers and their organizations encounter with colonization and empire, and especially the internationalist currents that produced workers who sought to shape a self-aware working class into a political project. 5) transnational radicalism and the role of “militant minorities, wherein migrating workers “enriched and deepened American radicals’ collective action and revolutionary vision in transformative ways,” –for example direct action or syndicalist strain that infused labor in the US in the early twentieth century.

Jim Barrett, emeritus professor of history at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, also noted that Montgomery is remembered for focusing on skilled white workers and their workplaces, and this became in some corners an avenue to suggest his scope was limited. But these criticisms missed how his work evolved. Barrett suggested that because Montgomery’s approach to class was conceptually capacious, his work can still be built upon. Montgomery was clear that it was not just the shopfloor where workers shaped and experienced class, but their neighborhoods, communities and all aspects of social experience. Montgomery’s critics have argued that his emphasis on class oversimplified or elided race, ethnicity and gender as categories of analysis, and Barrett took some effort to note the basis for that critique, but also to suggest those criticisms were oversimplifications of Montgomery’s work.

Still, for Montgomery, the social relations of production was a focus of his work, as he saw that as the “driving force” of historical change, something he would would remain laser-focused on. This focus dovetailed with his analysis of capital formation, managerial theory and practice, but Montgomery’s angle always kept workers in view. Barrett noted that new work on capitalism loses something by missing that dimension. Barrett noted that much of recent labor history has had less attention on the workplace, and that it might be impoverished as a result.

Barrett ended with a reminder that Montgomery insisted that to understand the full implications of workers history, the historian needed to pay attention not only to everyday experience, but to capturing three related levels of that experience—the local, the national, and the global. This is still a worthy agenda, and much of recent labor history has not managed to embed all three in the narratives.

Commenter Naomi R Williams, Rutgers University, began with a strong statement that the panel’s question mark was not necessary, and affirmed that Montgomery’s model was one of continuing relevance. Williams had used it when designing and researching their late 20th century study, A Blueprint for Worker Solidarity: Class Politics and Community in Wisconsin (released January 2025). Keeping workers at the center of a shifting political economy at local, national and global levels was especially important, they noted, to getting at the real stories of everyday life. The purported move away from class by critics betrayed a lack of understanding of how class was experienced and its complexity. Williams emphasized that pronouncements of their death or irrelevance of community studies had been premature and plain wrong. These were vital to help understand how the national and global political economy worked. Williams also applauded Montgomery model of scholar-activism.

Lorenzo Costaguta (University of Bristol) agreed that the question mark should be removed, and found that Montgomery’s study of capitalism from a global perspective was a continuing influence. He noted that like Montgomery, one did not have to adhere to world systems theory, but could use some of those concepts for our own purposes. He advocated that historians continue to broaden the conception of sites of production and workers intimate spaces of home, and to follow capitalist production sites with the worker left in. There is much to be done regarding comparative history, including broadening the scale of analysis to be more inclusive of other regions including the global South. He emphasized that we need more understanding of Marxism’s utility, and in particular advocated reading scholars such as Ellen Meiksins Wood and Robert Brenner. Costaguta emphasized the need to more carefully integrate race and radicalism through these comparative examinations.

There was a short but lively discussion. Perhaps the most provocative asked why labor historians are hesitant to go on the offensive about class as a category of analysis. Attendee Chad Pearson argued that there is much more vigorous defense of race and gender in the academy, for example.Toni Gilpin, a former Montgomery student, shared stories of how his mentorship could be a model, as well as his commitment to student-faculty activism. Others chimed in that even if one had not studied with Montgomery, his use of Marxism and his pointillist portraits of working-class life continued to inspire a new generation.