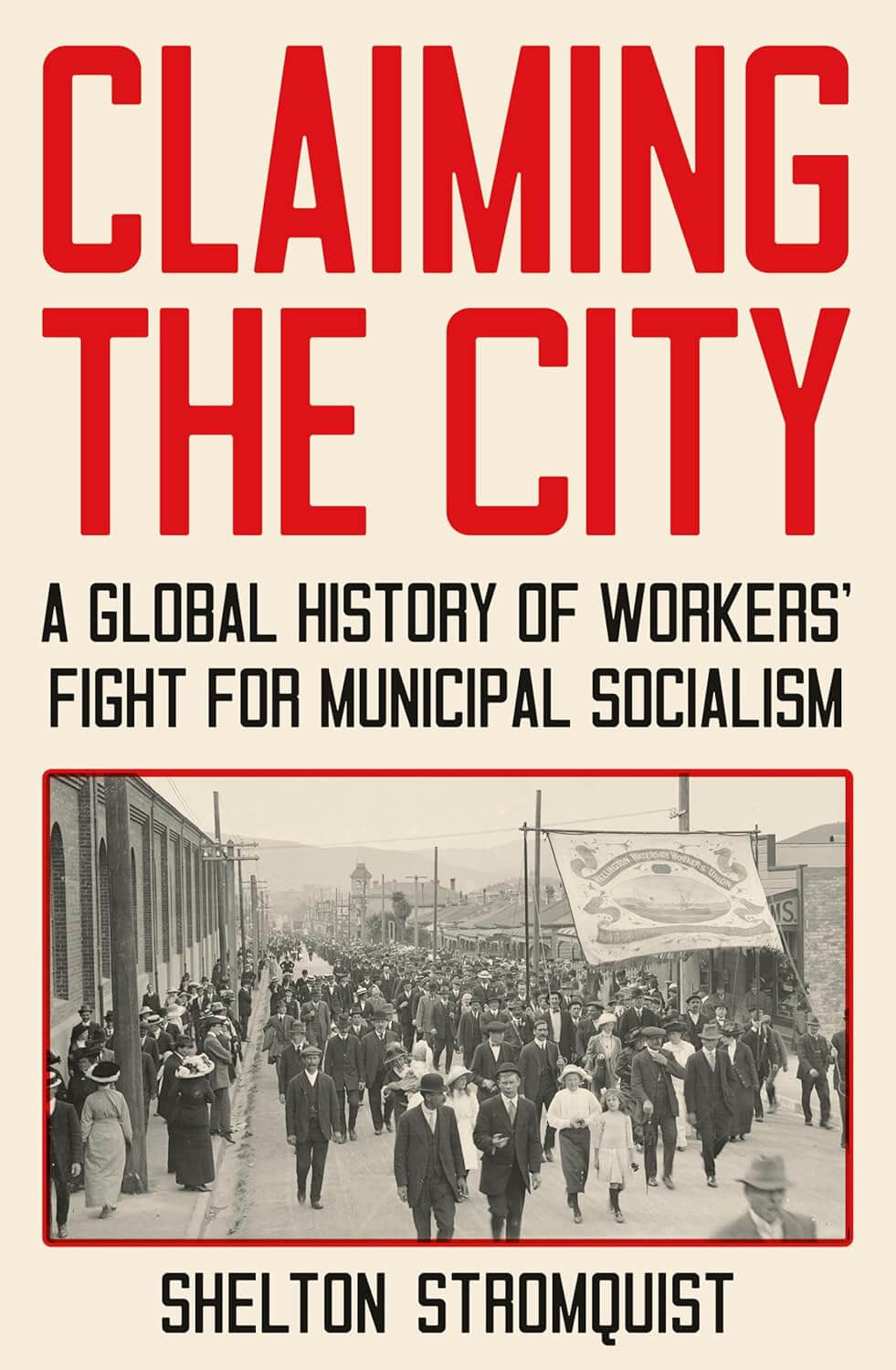

The stunning victory of self-identified “democratic socialist” Zohran Mamdani in New York City’s Democratic Party primary has sent a shock wave through the chattering class, the Democratic Party establishment, and their corporate backers. Long before Mamdani’s victory, the predictable red baiting was underway. It has only intensified since. Most commentators have no clue what “democratic socialism” means, let alone that there is such a thing as “municipal socialism”, with a long and highly relevant history of its own. Neglected in all the chatter and the instant analysis of the city’s electoral map is the way his platform and his popular appeal link his campaign to a long and robust tradition of municipal socialism in the US and globally. In fact, the considerable fruits of that tradition are all around us and largely go unmentioned. If elected, Mamdani would not be starting from scratch.

Neglected in all the chatter and the instant analysis of the city’s electoral map is the way his platform and his popular appeal link his campaign to a long and robust tradition of municipal socialism in the US and globally. In fact, the considerable fruits of that tradition are all around us and largely go unmentioned. If elected, Mamdani would not be starting from scratch.

Mamdani’s proposals for freezing rent and building more affordable public housing, for free pre-K child care, free bus service, and publicly-owned grocery stores build on the robust public municipal public sector that is now normative in cities—public water and sanitation, public transportation, public libraries, schools and swimming pools, paved streets, unionized public sector workers; and in many cases, municipal gas and electricity, public markets, and locally-constituted municipal welfare programs. These and other improvements have made cities more livable and engines of economic growth. They continue to attract diverse migrants in search of a better life. But underlying these practical reforms is a democratic socialist vision that promotes fundamental equality and democracy and that aspires to an even more expansive public sector.

We need only look back to the early 20th century to see the roots of these policies and the working-class politics that brought them into being. In places like Hamilton, OH, Milwaukee, WI, Butte, MT and hundreds of other US cities, and globally in thousands of cites like Bielefeld and Offenbach, Germany; Nelson and Bradford in the UK, Malmö, Sweden; Redfern (Sydney), Australia. The most stunning example was, of course, “Red Vienna”, where socialists governed from 1919 until 1934 and among other things constructed a vast infrastructure of affordable, rent-controlled public housing that continues today.

But Mamdani, like earlier municipal socialists, faces challenges to his municipal socialist vision and municipal “home rule”. Many of the early municipal socialist victories were short lived. In many cases, cities’ ability to set their own tax policy and to fund expanded public services, required state approval or state legislation. In Mamdani’s case that would apply to his proposition to raise state and city income tax rates on the very wealthy. City charters vary, but in many cases major policy initiatives require state sanction. Politically, sustained labor and socialist governance of cities has faced the challenge of fusion, where opposing parties realign to present unified opposition to socialist rule. In the case of Mamdani, the looming prospect of Eric Adams and Andrew Cuomo mounting “independent” campaigns might erode the Democratic majority through fragmentation and allow the Republican nominee to squeak through.

But like the municipal socialists before him, Mamdani has shown a capacity to draw new voters—younger and working class—into the electoral process. Using new social media today, like the local independent socialist press of the past, he has galvanized and energized segments of the population previously disconnected from local politics. The challenge, of course, is solidifying that political base to hold elected officials accountable and moving beyond charismatic leadership to building a programmatically committed and vigilant constituency. Sustaining municipal socialist governance requires party organization and discipline. And implementing that agenda over the longer term necessitates dedication and vigilance and avoiding the enticements of personal ambition.