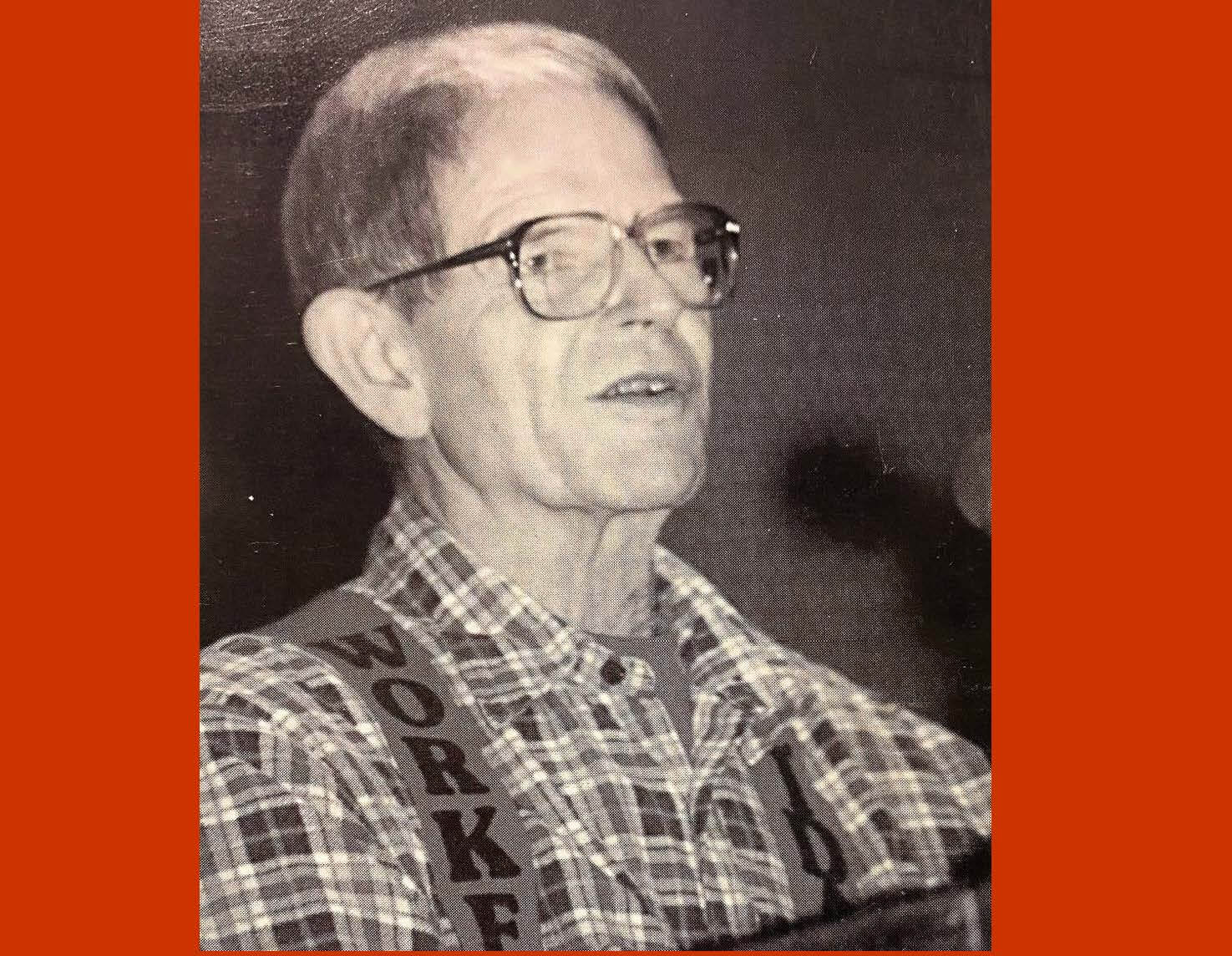

Staughton Lynd, one of labor history’s icons, died on November 17. He was an academic and activist when those combinations were reviled as unbecoming of a professional, and he was blacklisted from the profession for his bold anti-war stance. He became a labor attorney, moved to Niles, Ohio and was a strategic player in the fight against steel-mill shutdowns and the destruction of steel communities in Youngstown, Ohio.

I first met Staughton in the early 1990s when he came to St. Louis for a New Directions – UAW conference. A giant in the civil rights movement and anti-war movements, I knew him mostly in relationship to these struggles, and attempts to connect lessons from the labor history to the ongoing fights for a new structure for the labor movement to renew itself. That campaign withered away, and the UAW continued its plunge into cooperation and corruption. But some of the same people from that movement, such as St. Louis’ own Mike Cannon, are still involved in the current UAW reform efforts. There is a thread, Staughton suggested, one that is often missed, one that connects movements. He was a prime exemplar of that connection.

In any conversation, Staughton insisted on telling stories of people who had influenced him, such as Sylvia Woods, the UAW activist from Chicago featured in the classic film Union Maids (1976) who blamed union contractualism for labor’s decline. Or his mentor John Sargent from Inland Steel, who told him how steelworkers’ power grew without a contract that policed direct action, in comparison to the rest of the steelworkers locals which emerged supposedly more powerful because they had that contract in hand.

At the time I met him, Staughton was also proposing a project that became the book We Are All Leaders: The Alternative Unionism of the 1930s (1996). It was a book that was not that well-received by many labor historians, and he was hurt but not surprised that so many were eager to find flaws in the interpretation. It came on the cusp of other treatments that, in the wake of neoliberalism, looked at the New Deal and the CIO with romantic hindsight or were building the new framework of the the “rise of the right” as the key historical trend. The moment for criticism of the CIO had passed among labor historians, but not so for the labor activists who still experienced the undemocratic structures built during that time. Capital, Staughton knew, would not have had the robust power it acquired without the capitulation of labor leadership to its demands, and that required taking a more critical view of the CIO and its leadership.

Historian Bob Buzzanco, a native of Niles, Ohio, where Staughton and Alice Lynd lives, recorded this interview with them as part of the Green and Red Postcast in 2020. The podcast was rebroadcast yesterday beginning with a short survey of Lynd’s intellectual and activist contributions.

They note one error in the wrap-around introduction: “It was Herbert Apthecker, not David Dellinger, who went to Vietnam with Staughton and Tom Hayden.” ) and include this brief biography of him as well:

“Staughton Lynd was one of the most important American Activists/Scholars from the mid-20th Century onward. As a historian, he was one of the first prominent scholars associated with the “New Left” and he did pathbreaking work on the colonial war of liberation against the British Empire, situating it not just as a fight over Home Rule, but also “who should rule at home,” i.e. what type of class relations would exist in the new country.

Staughton was on the faculty at Spelman University where he and colleague Howard Zinn became active in the Civil Rights Movement (activity that cost Zinn his job there). Staughton became head of the Mississippi Summer Freedom Education Project, organized by SNCC. He then moved on to the faculty at Yale University, but that was short-lived. He traveled to northern Vietnam in 1965 as part of an antiwar contingent and the Liberals at Yale fired him for his political activity. After that he, and his wife, another acclaimed activist, Alice became lawyers specializing in Labor Law and Prison Reform.

The Lynds moved to Niles, Ohio (also Bob Buzzanco’s hometown) where Staughton became one of the leaders of a 1977 movement to save Youngstown, Ohio steel mills from closing down. He has been active in labor matters since and he and Alice also have defended death row prisoners and worked with military veterans on the issue of “moral injury.”

For more on Staughton, see, among others, his books Class Conflict, Slavery, and the United States Constitution: Ten Essays; Moral Injury & Nonviolent Resistance (with Alice Lynd); and The Fight Against Shutdowns: Youngstown’s Steel Mill Closings. There is also a good biogaphy of Staughton, Carl Mirra’s The Admirable Radical: Staughton Lynd and Cold War Dissent, 1945–1970.”