Today we continue our roundtable discussion on Nate Holdren’s Injury Impoverished: Workplace Accidents, Capitalism, and Law in the Progressive Era, just published from Cambridge University Press. Holdren delves into the history of the emergence of workers’ compensation law in the United States. Yesterday Eileen Boris introduced the series. The commentaries that follow look at the contribution from various perspectives. Today (August 11) Vilja Hulden discusses the gap between reforms and the situations they are meant to correct.

***************************

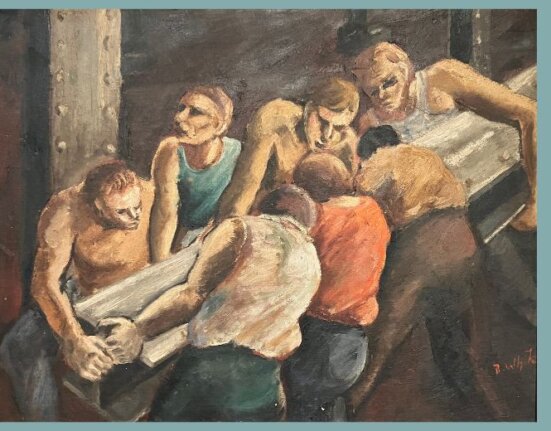

Nate Holdren’s Injury Impoverished, in recounting the way in which American society dealt with workplace injury in the early twentieth century, shines a light on the chasm that one often feels yawns between what a legal reform actually accomplishes and what a truly just society would look like. Holdren’s work raises important questions about how even well-meaning, significant reforms that fail to grapple with the full humanity of human beings produce systems that do not measure up even to the reformers’ goals, let alone grander ones.

Holdren tells the story of how the U.S. moved from the nineteenth-century court-based structure of employee injury law to the workers’ compensation laws established in the early twentieth century. He shows that both systems were deeply flawed: each devalued workers, only in different ways. The earlier system, which Holdren calls the “tyranny of the trial,” was slow, hard to access, and rarely resulted in workers receiving compensation. Sometimes, though, it provided some recognition of the non-economic harms suffered by the injured worker as well as a forum for telling the story of what the injury meant in the worker’s life. The newer regime of workers’ compensation yielded monetary redress more reliably. Yet it resulted in a “tyranny of the table” that abstracted the mosaic of suffering caused by industrial injuries into so many tabular representations of the monetary value of a hand or an eye, undergirded by a logic “treating working-class people impersonally and as objects of instrumental use” (9).

Holdren acknowledges that the reformers pushing for workers’ compensation laws were not blind to the suffering caused by workplace accidents. Nor were they insensitive to the complex ways in which the impact of those accidents reverberated in the lives of injured workers. As Holdren points out, reformers like Crystal Eastman and William Hard explicitly tried to bring their middle-class audiences to a “recognition of working-class humanity,” arguing against, as Eastman put it, the “opinion many hold, that poor people do not feel their tragedies deeply” (59). And yet, reformers’ efforts produced the tyranny of the table: a set of compensation mechanisms that discriminated against those with preexisting injuries and that offered some monetary compensation but little affirmation of humanity.

Why? According to Holdren, part of the answer lies in the reformers’ perhaps implicit decision to prioritize “justice as distribution,” or economic compensation for injuries, over “justice as recognition,” or “the human need, right, and moral imperative to be seen as a fellow human being with dignity” (35). Justice as distribution mattered: it acknowledged the direct economic impact of a workplace injury as well as its financial ripple ef fects in a worker’s life and in those of his or her family members. Reformers tallied up these ripple effects in stories and statistics about widows being reduced to supporting their children through “immorality” and children cutting short their schooling to support the family when a workplace injury cost the father his earning capacity. These stories encapsulated an important point: a system that provided faster and more reliable compensation for injury could provide fairer outcomes while also heading off escalating social costs of accidents. At the same time, focusing on justice as distribution encouraged reformers to speak in terms of societal rather than individual needs. In building a system that tried to allocate compensation efficiently and predictably, they made compensation impersonal and instrumental, linking it to one’s (lost) earning capacity rather than to the deeper costs of the injury.

fects in a worker’s life and in those of his or her family members. Reformers tallied up these ripple effects in stories and statistics about widows being reduced to supporting their children through “immorality” and children cutting short their schooling to support the family when a workplace injury cost the father his earning capacity. These stories encapsulated an important point: a system that provided faster and more reliable compensation for injury could provide fairer outcomes while also heading off escalating social costs of accidents. At the same time, focusing on justice as distribution encouraged reformers to speak in terms of societal rather than individual needs. In building a system that tried to allocate compensation efficiently and predictably, they made compensation impersonal and instrumental, linking it to one’s (lost) earning capacity rather than to the deeper costs of the injury.

Strategically, emphasizing economic compensation for injuries, or “justice as distribution,” may have been a smart choice. That approach offered efficiency and predictability for employers, making compensation more acceptable to those who held the strings of economic power. For employers, especially large ones, having to go to trial over a worker’s injury claim carried substantial risk: one might too often find oneself paying large sums at the behest of fickle juries. If compensation was instead determined by law and administrative practice, one could budget and insure for it, while also avoiding a confrontational trial that might inflame labor relations.

Defining justice as recognition of workers’ humanity would have posed a much greater challenge to employers. Compensation systems allowed employers to “keep employment private and depoliticized” (107). Reforms seeking to force employers to recognize workers as full human beings rather than as collections of body parts with prices attached, in contrast, would have forced an entirely with an industrial system that chewed up bodies like candy.

Promises of efficiency and predictability thus eased the passage of workers’ compensation laws by making them at least somewhat palatable to employers and other powers that be. But that passage came at a price. It entailed discarding the effort to grapple more deeply with power relations in the workplace, with the (im)morality of having to risk life and limb to put food on the table, and with the more general impact of one’s working life on the rest of one’s life. It also had unintended consequences: workers’ compensation was supposed to give employers an incentive to create a safer workplace, but it led instead to weeding out workers with previous injuries or underlying health conditions that made compensation more likely or more expensive.

In the beautifully written introduction, Holdren notes: “I hope that when readers finish my book they will find our legal handling of employee injury newly unnerving” (6). Yes. At the same time, I’m left somewhat puzzled. The concrete problems with compensation that Holdren discusses at some length—particularly the new proliferation of employee health screenings to help employers avoid hiring or retaining workers considered bad compensation risks, but also the stinginess of compensation—seem to me to stem from specific features of the laws and to have little to do with standardization or commodification. Nor is it particularly difficult to imagine purely “technical” fixes for many of the system’s problems. Specific features, however, are not Holdren’s concern; he emphasizes the distastefulness of the commodification of people involved in the standardizing of injury compensation and the aggregating language of “human capital.” These, he points out, constituted a “moral thinning: from murder to statistics” (116).

I agree that we accept workplace hazards far too blithely—something we became suddenly and acutely aware of this strange spring, though to what effect remains to be seen. But I’m not convinced that it is in and of itself morally objectionable to set prices for limbs, or eyes, or even lives, even as we all understand that such losses cannot actually be compensated in money. In fact, I’m not quite sure if Holdren means to say it is. I would have liked to see a more explicit discussion of the concrete consequences of “moral thinning.” These seemed to me to be left rather unexplored, apart from Holdren’s brief treatment of how a focus on compensation precluded a rethinking of whether the practices that led to injury should have been tolerable in the first place (82-83). I am thinking here of discussions along the lines of those in Michael Sandel’s What Money Can’t Buy (which Holdren briefly cites in a slightly different context) about how monetary compensation “crowds out” the civic or moral meaning of an action and tangibly changes people’s choices.[1] And I would have liked to see a discussion of whether “impersonal” forms of compensation are necessarily less respectful. In some ways, being entitled to standardized, impersonal, actuarial-table-style compensation seems not just more efficient in terms of distributive justice but potentially more dignified. Courts sometimes offered an opportunity to tell a fuller narrative of the “experiential truths of injury” (116), but that could also be construed as having to play up one’s injury to a jury for all that it might be worth (as Holdren is aware).

To me, then, it seems that the book could have made more room for exploring moral complexity, and of the difficulty of achieving, or even designing, systems that are just. To take just one last example: I agree that “to create an economy that does not kill” (271) is a worthy goal in principle. Yet human activity does in fact kill, and we all know the flaws of arguments along the lines of “if even one life is saved…” It is not merely capitalist society, nor economic activity, that poses the challenge of balancing protecting human life against having a functioning society. A discussion of how in other contexts—say, car crashes—would have been welcome. Such a discussion would have set a bigger context for a more precise grappling with the locations and origins of injustice and inhumanity in the workers’ compensation system.

Mostly, though, these are quibbles rather than disagreements, and I realize that, to an extent, I am doing the usual reviewer thing of complaining that Holdren did not write the exact book I wanted to read. He did, though, write a very good book (and that includes the many long discursive footnotes, of which I am a great fan in general, and which Holdren puts to delightful use). What’s more, he wrote a book of great importance, one that I dearly hope will be widely read. The intellectual depth, human feeling, and excellent research that this book demonstrates would make it relevant at any time. But they make it indispensable reading at this moment when, in the middle of a pandemic, we are (finally) asking how much we can ask people to sacrifice in the pursuit of a livelihood, and what is due to those who risk their lives so the more fortunate among us will continue to have food, health care, and the other necessities of life. There is much to learn here—not least from Holdren’s careful attention to the individual stories of hardship and suffering. These succeed superbly in underlining that justice cannot simply mean rote monetary compensation but requires unequivocal recognition that working-class people are full human beings with lives that are just as complex, rich, and valuable as those of, say, academics.

Mostly, though, these are quibbles rather than disagreements, and I realize that, to an extent, I am doing the usual reviewer thing of complaining that Holdren did not write the exact book I wanted to read. He did, though, write a very good book (and that includes the many long discursive footnotes, of which I am a great fan in general, and which Holdren puts to delightful use). What’s more, he wrote a book of great importance, one that I dearly hope will be widely read. The intellectual depth, human feeling, and excellent research that this book demonstrates would make it relevant at any time. But they make it indispensable reading at this moment when, in the middle of a pandemic, we are (finally) asking how much we can ask people to sacrifice in the pursuit of a livelihood, and what is due to those who risk their lives so the more fortunate among us will continue to have food, health care, and the other necessities of life. There is much to learn here—not least from Holdren’s careful attention to the individual stories of hardship and suffering. These succeed superbly in underlining that justice cannot simply mean rote monetary compensation but requires unequivocal recognition that working-class people are full human beings with lives that are just as complex, rich, and valuable as those of, say, academics.

[1] Michael J. Sandel, What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2012).