Thanks to Professor Rosemary Feurer and the LaborOnline team for another opportunity to interview Robert W. Cherny, this time about his 2024 book, The Coit Tower Murals: New Deal Art and Political Controversy in San Francisco. Dr. Cherny is emeritus professor of history at San Francisco State University. He has written seven books and co-authored three others about American politics, labor, and art. Additionally, he’s co-edited two anthologies and collaborated on two textbooks. Professor Cherny is the author of more than 40 journal and anthology articles which focus primarily on the political and labor history of California and the West. His book Harry Bridges: Labor Radical, Labor Legend (2023) is a monumental, prizewinning biography of one of the most iconic figures in the annals of US labor. Cherny’s other recent books include Victor Arnautoff and the Politics of Art (2017); Seattle/Seiatel:The American Commune in the Soviet Union (2021), co-authored with Seth Bernstein; and San Francisco Reds: Communists in the Bay Area, 1919-1958 (2024). A new book, A Short History of San Francisco, is in production for release in 2026.

Professor Cherny, so much of your work deals with politics and labor. How did you come to write a book about the New Deal murals in San Francisco’s Coit Tower?

Writing a book about New Deal art proceeded logically from other things I’ve been doing. I started out focused on political history, asking especially what motivates individuals to support particular causes. My doctoral dissertation was about voters in the Populist and Progressive era and why they supported the Populists and Progressives. Interest in what motivates people to support change runs through a number of my projects since then. My biography of Victor Arnautoff is about an artist who was born in what is now Ukraine, came to San Francisco, but eventually joined the Communist Party. He left California and lived the rest of his life in the Soviet Union. What motivated someone to make those choices? My book about Harry Bridges asks, why does a young man growing up in Australia become a labor leader and become so close to the Communist Party? He was adamant that he was never a CP member, and I took him at his word, but he took public positions that supported very left causes. My book on San Francisco Reds is about why a group of people joined the Communist Party, what they did, and why most of them chose to leave. It is about political choices related to the larger economic and political system and wanting change in a left direction.

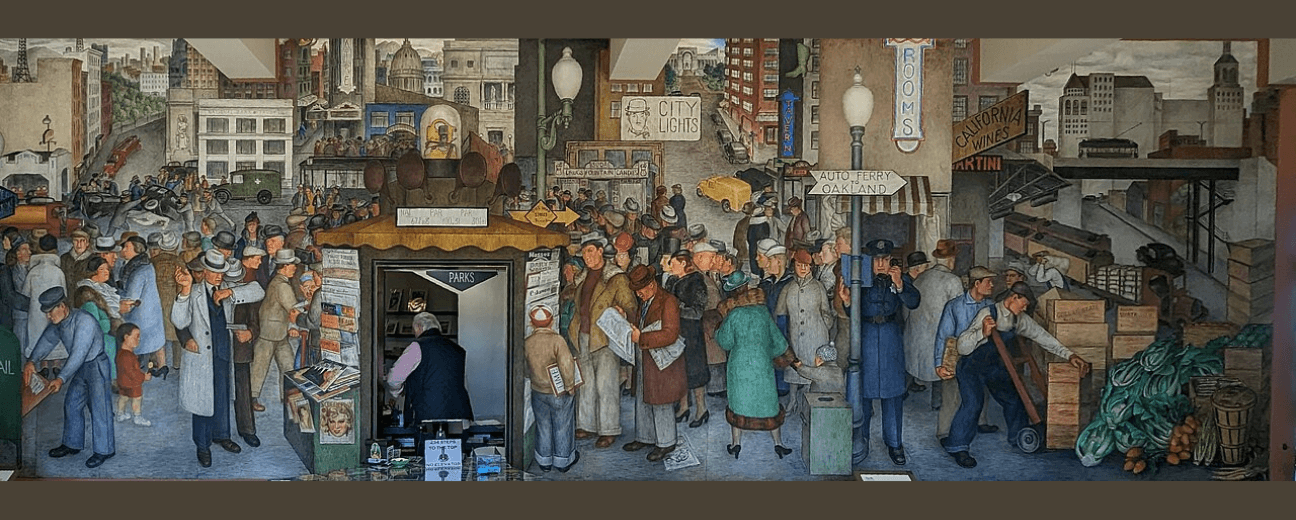

So how do we get from that to writing about Coit Tower murals? These last three books—the biography of Arnautoff, the biography of Bridges, the book on the San Francisco Reds—cover long time periods, but they all center very much on San Francisco in the 1930s, a time that was formative for the people I was studying. So I spent a lot of time looking at San Francisco in the 1930s for all of these books. The research for the Bridges book sent me in the direction of the other books; all three are clearly related–in my mind anyway. I think of them as my Left Coast trilogy. The Arnautoff book especially took me in a direction I’d never been in, which was looking at art, because Arnautoff was a New Deal artist. He did murals under all of the major New Deal arts programs. I got interested in his Coit Tower mural, City Life. It has been described as one of the most significant examples of the influence of Diego Rivera on American New Deal artists. More generally, the Coit Tower murals as a group, done by twenty-five artists, have been described as some of the best examples of cooperative efforts under the New Deal art projects.

After my 2017 book on Arnautoff, I got involved in defending Arnautoff’s murals at George Washington High School in San Francisco. Two of them were controversial. In one, Arnautoff included the dead body of an American Indian warrior. The artist was depicting the genocide of Indigenous Americans as one of the great injustices of American history. An opposite mural shows enslaved African Americans. In that mural, Arnautoff made it clear that George Washington was a slaveowner, something that was glossed over in the 1930s just like the dispossession of Indigenous Americans was glossed over at that time. Arnautoff was using his art to educate high school students. But, in 2017, this was seen as injurious to Indigenous and Black students. Some school board members wanted to erase those murals. I got pulled into this public policy question in a way I had never been pulled into any public policy question throughout my entire time as a historian and a teacher. I argued that there were other ways of dealing with the problem than to destroy the murals. I was interviewed—local papers, The New York Times, even a German newspaper—so my name was out there as a defender of New Deal art. Then, in 2022, the University of California, San Francisco, announced they were going to demolish a building that had some important New Deal murals. Those murals were threatened. I was again pulled into the public policy arena defending New Deal art.

By then I’d finished all the research I’d been doing since the mid-1980s focused on Bridges, Arnautoff, and the San Francisco Reds book. I sent all my research files to the Labor Archives at San Francisco State University. But at that point, it occurred to me that I had also done a lot of research about the Coit Tower murals. I had researched the historiography and the creation of the murals as part of a team preparing National Register nomination. There is a very good book about those murals by Masha Zakheim, the daughter of Coit Tower artist Bernard Zakheim, but it is now out of print. The company that published it no longer exists. I talked to Masha Zakheim’s heirs and to Bernard Zakheim’s grandson, who had been part of the publishing company. However, there seemed no possibility that Masha Zakheim’s book would be republished. I thought, “Well, I’ve done about seventy-five percent of what I need to do to write a book about the Coit Tower murals.”

Unlike any book I’ve written before, I conclude with a discussion of public policy. I argue that New Deal murals should not be destroyed because they are historical artifacts that tell us important things about the time when they were created.

In mid-2023, my San Francisco Reds book went into production. I knew that in October 2024 there would be an event to celebrate the ninetieth anniversary of the Coit Tower murals. I contacted my editor at the University of Illinois Press and said, “This would be a good book for you. There’s an event, but with a tight deadline. Can you have the whole book done by October 2024?” They said, “Yes.” I did more research, revised pieces I’d written before, and stitched it all together. Getting permission from the City Attorney to use the San Francisco Arts Commission’s high-resolution color photos of the murals took time. But it all came out OK. I didn’t have to pay to use the photographs. And the press did a terrific job. There are sixty beautiful color plates. The book was even priced to sell at Coit Tower and other outlets in town. There are currently more local bookstores with the Coit Tower book than all my other books put together. But this book isn’t just for tourists. It also looks at what art critics and art historians have had to say and at the murals’ influence on subsequent New Deal art. And, unlike any book I’ve written before, I conclude with a discussion of public policy. I argue that New Deal murals should not be destroyed because they are historical artifacts that tell us important things about the time when they were created.

It’s impressive that you published a major book in 2017 and three others of similar quality between 2021 and 2024 despite suffering a life-threatening infection in 2017 that cost you many months. Your resilience is heroic. How did you physically and psychologically manage to accomplish so much so quickly?

Thank you for the compliment. I started doing the research for all this in 1985 with the Harry Bridges book. The decision to write that biography refocused my research and my teaching to the 1930s. I spent the next fifteen years doing archival research at every opportunity, every summer, every sabbatical leave. In the end, I had this huge collection of mostly primary sources. Along the way, when I was doing research in Moscow on Bridges, it became clear to me that there was a different book here about the Communist Party in the San Francisco Bay Area. So I was already working on two books in my head by 2000. I came upon the Arnautoff project in 2010. So, by then, I had three books in my head for which, in various ways, I’d done a lot of archival research. In 2012, I decided, “I have to stop teaching so I can get these things written.” I remembered what Richard Hofstadter said to the entering class of graduate students at Columbia when I started in 1965. He pointed out that when Frederick Jackson Turner died, he had file cabinets full of research he had never written up. Hofstadter said something like: “Archival research is interesting, we all love to do it. But if you’re the only one who knows what’s there, you are not doing your job. You have to share what you’ve learned, and put it out there for others to read and respond to.”

In 2012, I was 69. I knew I had to finish these books. So I gave up teaching, walked in my last commencement procession, and was declared emeritus. I knew I had to finish all this work.

I’d still like to know how you made such a psychological and physical comeback from a life-threatening infection and managed to complete all that stuff.

It did not occur to me not to, Harvey. From the middle of 2017 to the middle of 2018, I spent much of my time flat on my back in bed from pain. But when you’ve got filing cabinets full of research in the house and a computer that you can sit on your lap and type on, it’s fine. It was all in my head. It just needed to get it into the computer.

Getting back to the Coit Tower murals, can you describe any new findings you encountered in your research? Are there any new conclusions in your writing about the murals?

There’s another book that treats the Coit Tower murals. I’m not going to name the author. He concluded that there was a Communist cell at Coit Tower that was putting Communist propaganda into the murals and that many of the artists were using their murals to comment on the 1934 Pacific Coast longshore and maritime strikes. I knew that Arnautoff had later become a Communist and that Bernard Zakheim had been one. Zakheim even showed a man reaching for Marx’s Das Kapital in his mural called Library. Maybe there was something there. However, what I found was contrary evidence. My research made clear that Arnautoff did not become a Communist until 1937 or 1938, well after he was painting in Coit Tower. It didn’t look to me like he could have possibly been in charge of a cell at Coit Tower in 1934.

Then I looked at the record of the dates when the artists got their final checks–that is, when they finished their murals. All but about five had been paid off by April 28. Some had been paid off as early as the beginning of April. The strike started on May 9. They could not have been putting anything about the strike into their murals if they’d already finished their work before the strike started. For example, there’s a mural by Otis Oldfield that shows the northern waterfront in San Francisco, which you can see from Coit Tower. This previous author said something like, Oldfield showed no picket lines, no ships in the bay, so he was consciously avoiding any reference to the strike going on right below him. Well, I found a newspaper photograph of Oldfield’s completed mural in February and the strike started in May. This same author said the artists could see the battles on the docks and the struggles with the police. Nearly all of that happened far away on the south waterfront and in June and July, not in April. I tried to set the record straight in my book.

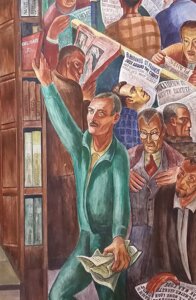

There was a major controversy when Clifford Wight put a hammer-and-sickle on a wall over a window. Wight claimed that he was just showing what is in the American scene today. The American scene was what the artists were all supposed to be depicting. Well, that didn’t wash. Once someone in authority spotted what Wight had done, the image was eliminated. John Langley Howard’s mural, California Industrial Scenes, has the most direct depictions of the Great Depression. He has unemployed in the center. On the left side, there’s a group of May Day marchers. One is holding a copy of The Western Worker, the newspaper of the Communist Party. The headline says, “March against hunger, war, and fascism.” The Western Worker banner, with a hammer-and-sickle in the middle, was painted over. This was clearly an act of political censorship.

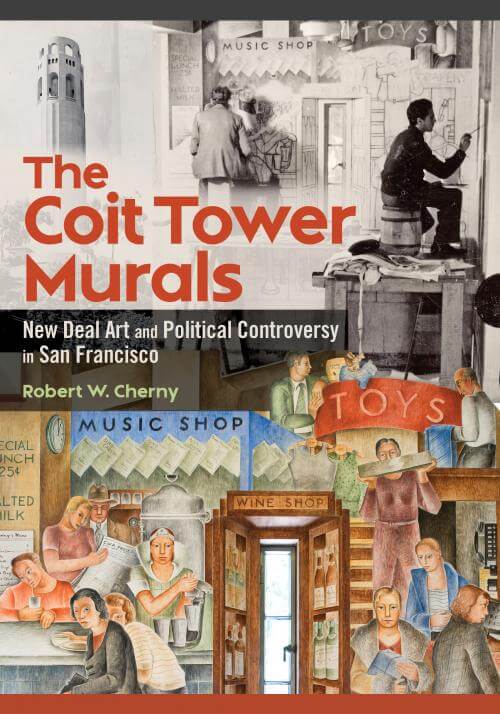

The cover of the book is complex and attractive. Is it supposed to convey anything specific about the book?

I didn’t design the cover. I learned long ago that authors get to make recommendations about covers but you accept what you’re given. I’ve always been pleased with what people come up with, especially at the University of Illinois Press. I was able to work with Illinois on covers for my four books with them. I liked what they did with The Coit Tower Murals. In the upper left is a picture of the tower. In the upper right, there are two of the artists at work. At the lower half, there’s the finished mural that one of the artists is working on up above. It really fits together very nicely.

The book starts with sections on the 1930s San Francisco art scene, the influential Mexican murals tradition, and New Deal art politics. That sets the context for everything. Then there’s a long section with lots of color plates and explications of the murals. After that we learn about political controversies connected to the Coit Tower and other San Francisco mural projects. Is there anything else about the structure of the Coit Tower book that readers might want to know about?

No, that pretty well covers it. But note that I introduced the book with a quote from Ralph Stackpole, one of the Coit Tower artists. In 1941, an outraged taxpayer went to the mayor and said, “This is Communist art, it should be destroyed.” Stackpole responded, “Prejudices grow; they might even grow to the actual point of having the murals destroyed. Then next would come the books.” In the context of 1941, he was talking about the Nazis burning books and art. I follow Stackpole’s quotation with a quotation from PEN America about book banning in U.S. schools and libraries during 2022-2023. So, yes, art needs to be protected, but so do books, especially in a digital age.

There were a few women artists and some minority group members who worked on the murals. Any comment on their role?

I looked at the proportion of women who were in leadership in the 1930s in the San Francisco Art Association. The proportion of women who were in that leadership and the proportion of women master artists at Coit Tower was almost the same. The largest murals were assigned on the basis of experience. An experienced woman, Maxine Albro, got one of the largest murals. Other women who had some experience also got murals.

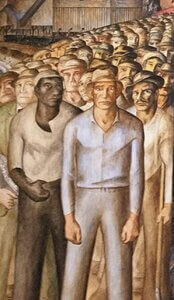

The other question is about ethnicity. The population of San Francisco in 1934 was about ninety-two percent white. There were two non-white artists at Coit Tower. Out of the twenty-five master artists, that was eight percent. That was about what the percentage of non-whites was in the population of the city. Then there’s the question of depictions in the murals themselves. Are people of color in the murals? It’s a question that I don’t think really came up for past art historians or art critics. I looked very carefully at the murals and at photographs of them. I spotted quite a few examples of how the artists incorporated people of different races. In Stackpole’s mural, there’s a depiction of a fruit and vegetable cannery and nearly all the women working there appear to be Asian. And there are other people of color, all well integrated into other murals. Looking carefully at each mural is the only way you can answer that question about ethnicity, because none of the artists in their oral histories said anything about setting out to depict people of color. They just did it.

How do the Coit Tower murals speak to us today?

The Coit Tower murals were done under the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP). One of the objectives of Edward Bruce and Forbes Watson, who were in charge of the PWAP in 1933-34, was to democratize art. They wanted artists to create art that ordinary people could relate to. They also hoped to open the federal commissioning process to more artists. All that ended with the New Deal art programs. Representational art, emphasized by the New Deal, became passé after World War II. Abstract expressionism took over. The CIA liked abstract expressionism and funded it covertly because there was no obvious political message there. It took art critics a long time to return to giving serious attention to New Deal art. We never really got back to democratizing art and making it available to large numbers of people until recently. In San Francisco, we have lots of new public art on schools and on people’s houses. In the Mission District, they’re even on garage doors. The revival of bold, colorful, political murals in the city’s Mission District stems in significant part from the same place as the Coit Tower murals. They go back for inspiration to Diego Rivera and the other Mexican muralists of the nineteen-twenties and nineteen-thirties. As someone who has studied the public art of the 1930s, I find it really satisfying to see this explosion of public art in San Francisco.

Authors

-

Harvey Schwartz is curator of the ILWU Oral History Collection at the union’s library in San Francisco. His most recent book is Labor Under Siege with Ronald E. Magden. Other books include The March Inland: Origins of the ILWU Warehouse Division, 1934-1938 (1978; rpt. ILWU 2000); Solidarity Stories: An Oral History of the ILWU (2009); and Building the Golden Gate Bridge: A Workers’ Oral History (2015). He holds a Ph.D. in history from The University of California, Davis.

-

Robert Cherny is a Professor of History at San Francisco State University. He writes about Progressive-era politics, Populism, labor, and the Cold War. His recent works include Harry Bridges: Labor Radical, Labor Legend (2023) and The Coit Tower Murals: New Deal Art and Political Controversy in San Francisco (2024).