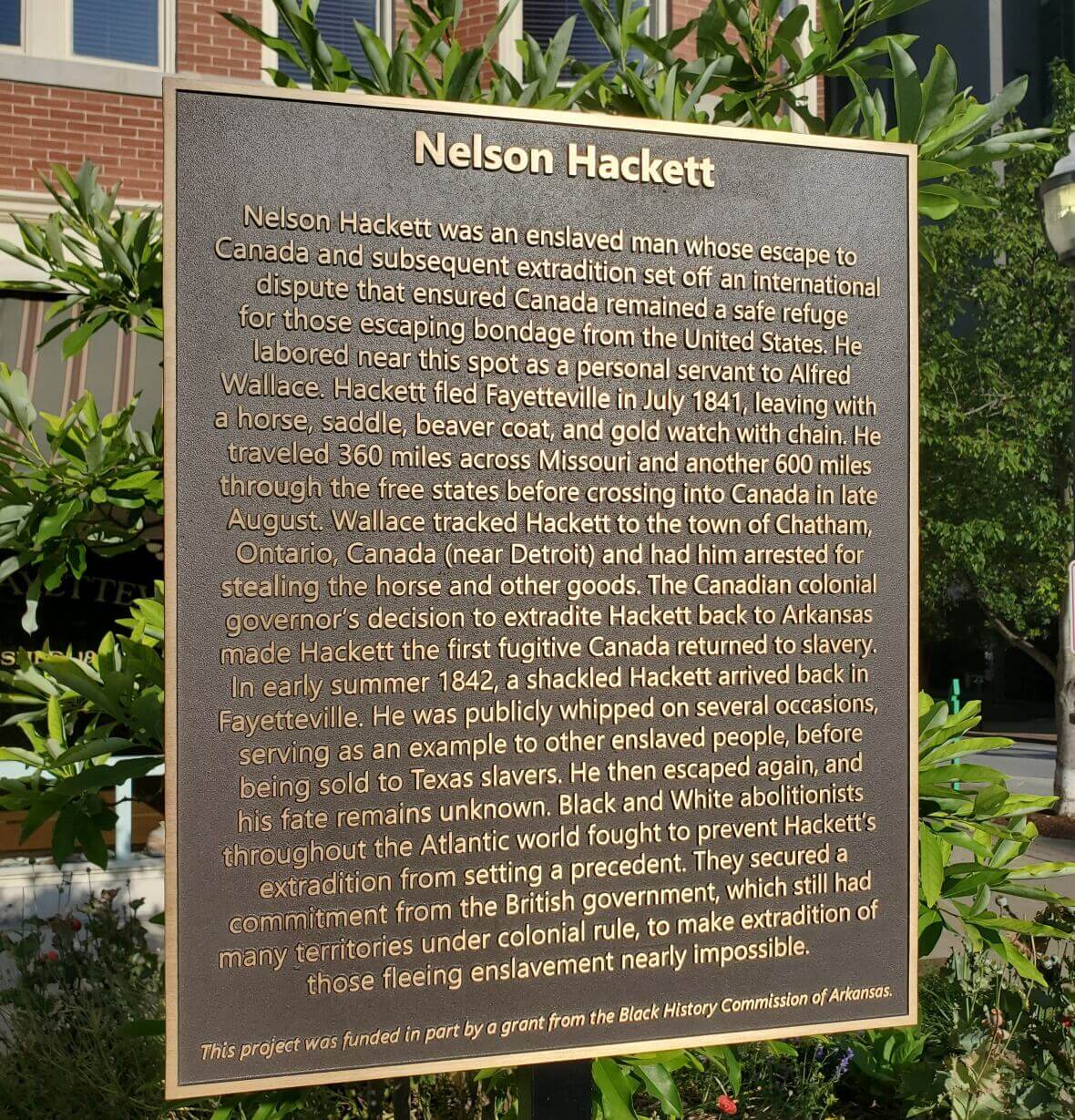

Over the last two years, the City of Fayetteville, Arkansas, working with the University of Arkansas Humanities Center, has erected a historical marker, renamed a major street, and sponsored a public mural to honor Nelson Hackett, an enslaved worker who fled the town in 1841 and set in motion the events that secured Canada as a safe haven for those enslaved laborers fleeing bondage in the U.S.

These efforts are the result of the Humanities Center’s Nelson Hackett Project. As the project’s director, I was aware that both the broader public and the scholarly community were largely unaware of Hackett’s story when the project began, but things are starting to change. The Nelson Hackett Project’s website—with a short narrative and documents—went live in 2020. Since that time, in addition to the marker, the street, and the mural, there has been a NEH Summer Workshop for K-12 teachers from across the nation, numerous podcasts, and public outreach to community groups as well as a scholarly conference with a forthcoming edited volume.

Hackett fled slavery sometime in the middle of July 1841, with a few items taken from his enslaver, including his fastest horse. Hackett made his way 360 miles through the slave areas of Arkansas and Missouri before finally crossing the Mississippi River near Quincy, Illinois. From there, he traveled through the free states of Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan to Detroit, probably taking the Underground Railroad’s so-called “Quincy Line.” Hackett then crossed the Detroit River into Canada, where he thought “the humanity of the British law made him a free man as soon as he touched the shores of the country.”[i] He quickly settled in Chatham in present-day Ontario about 45 miles east of Detroit.

Hackett’s enslaver, though, tracked him to Chatham, had him arrested for stealing items on his way out of Fayetteville, and demanded his extradition to Arkansas to stand trial. At the urging of influential Canadians in the Detroit borderlands and the leaders of the Legislative Assembly of United Canada, Canada’s governor-general returned Hackett to Arkansas and to bondage. With his extradition, he became the first fugitive that the colony returned to bondage. Hackett arrived back in Fayetteville in the summer of 1842 but escaped again. His fate remains unknown.

Hackett would also be the last fugitive returned to slavery by Canada. The leaders of Detroit’s free Black community feared that Hackett’s extradition would prompt slavers to use criminal charges as pretexts to secure the return of fugitives and “Canada will no longer be an asylum for our unfortunate brothers.”[ii] They alerted the trans-Atlantic abolitionist community. Abolitionists, including Lewis Tappan, Gerritt Smith, and Thomas Clarkson, then used Hackett’s case to lobby the British government to stop such extraditions. Their efforts became even more urgent in late 1842 when the U.S. and the British signed the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, which seemed to authorize such extraditions. As one abolitionist told Parliament, “Nelson Hackett will serve for a complete illustration” of the “evil . . . involved in the Treaty.”[iii]

The leaders of Parliament refused to formally amend Washington-Ashburton to exempt fugitive slaves for fear that the U.S. Senate would reject the entire treaty but discretely told abolitionists that no more fugitives from slavery would be extradited back to bondage. As the secretary of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society later explained, “in our communications with Lord Ashburton, with Lord Aberdeen, then the Foreign secretary, . . . it was most clearly understood that fugitive slaves were to be excepted from the operation of the treaty.”[iv] Abolitionists used Hackett’s case to ensure that Canada remained the promised land for those fleeing slavery.

Starting in 2023, the Nelson Hackett Project began working with the City of Fayetteville on public-facing projects to honor Nelson Hackett and make him part of the community’s civic memory.

- In the Summer of 2023, the city, with grant money from the Black History Commission of Arkansas, erected a marker on the town square, near where Hackett’s enslaver had a general store.

- Later in 2023, the city renamed a major thoroughfare Nelson Hackett Boulevard. The street had originally been constructed at the start of the civil rights era to separate the Black community from the core of the city. The renaming, though, was part of a larger project, including traffic abatement and new street crossings, to reconnect the historic Black neighborhood to the rest of the city.

- Last year, the city’s Arts Commission unveiled a public mural along Nelson Hackett Boulevard celebrating Hackett’s life and flight. Painted by Joëlle Storet Holt, a local artist, the mural portrays Hackett’s escape as the beginning of a long history of local Black resistance to slavery, Jim Crow, and white supremacy.

The Nelson Hackett Project is an on-going public humanities program dedicated to making Hackett’s story known to the people of Arkansas and the world. For more information, contact Michael Pierce (mpierce@uark.edu).

[i] “The Petition of Nelson Hackett, a Man of Colour, now confined in the Gaol of the Western District,” in Canada: Copies of a Despatch from the Governor-General of Canada to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, of the 20th of January Last, Relative to the Surrender of Nelson Hackett, a Person of Colour, in the Demand of the Authorities of the United States, as a Fugitive from Justice (London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1842), 7-8

[ii] “Fugitives from Justice—Public Meeting at Detroit,” Signal of Liberty (Ann Arbor), March 9, 1842, p. 3

[iii] Charles Stuart, “The Ashburton Treaty,” Patriot (London), October 13, 1842, p. 688.

[iv] Speech of John Scoble, December 19, 1860, at Toronto, reprinted in The Story of the Life of John Anderson, the Fugitive Slave (London: William Tweedle, 1863), 45-46.