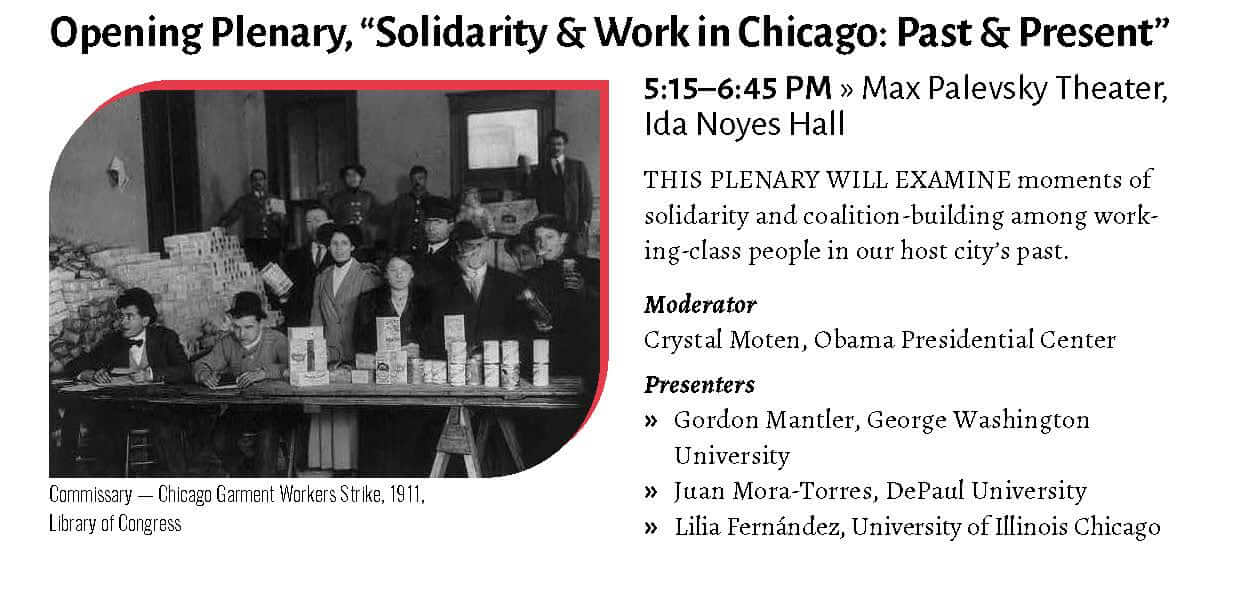

This year’s LAWCHA conference began with a reminder that we have come to a particular place, with a particular history: Chicago. Three scholars of Chicago, its working-class, and its politics spoke at the opening plenary on Thursday night to situate us.

First up was Lilia Fernández, who is one of the organizers of the conference. She gave an overview of the long history of Latino workers in Chicago, starting in the 1920s, when Mexican and Puerto Rican workers made up sizeable proportions of the workers in a variety of major Chicago industries, like packinghouses and railroads. A centerpiece of her talk was a 1953 factory fire, in which many of the victims were Puerto Rican – a fact noted in Puerto Rico but not in Chicago press coverage. She also told the stories of Latino workers in television manufacturing and garment manufacturing struggling not only against their bosses but against their unions, demanding fair representation.

First up was Lilia Fernández, who is one of the organizers of the conference. She gave an overview of the long history of Latino workers in Chicago, starting in the 1920s, when Mexican and Puerto Rican workers made up sizeable proportions of the workers in a variety of major Chicago industries, like packinghouses and railroads. A centerpiece of her talk was a 1953 factory fire, in which many of the victims were Puerto Rican – a fact noted in Puerto Rico but not in Chicago press coverage. She also told the stories of Latino workers in television manufacturing and garment manufacturing struggling not only against their bosses but against their unions, demanding fair representation.

Next up was Gordon Mantler, who spoke drawing from his recent book on Chicago mayor Harold Washington. As the plenary started, my social media had been gearing up for Thursday night’s New York mayoral candidates’ debate, where Zohran Mamdani defended himself against charges of managerial inexperience by pointing out that he is managing the 36,000 campaign volunteers who are knocking on a million doors in the five boroughs. So I was especially primed to hear in Mantler’s talk a warning about the difficulties that ensue when social movements turn to electoral politics. It’s easier to win an election than to govern, he pointed out – something of which New Yorkers are, of course, well aware. As an example, replacing the top of a city bureaucracy doesn’t automatically fix the bureaucracy; Mantler cited the Chicago Police Department and public housing authority as examples where Washington putting in a new boss was inadequate. Perhaps most suggestively, Mantler warned about the difficulty of coalition politics after the social movement has won its electoral victory. Some members of Washington’s coalition wanted to end patronage altogether, while others just wanted a slice of the patronage for themselves; navigating disagreements with your elected political friend is treacherous. Should Mamdani win New York’s mayor’s office, he should read Mantler’s book.

If I was thinking about New York electoral politics with one part of my brain, with another I was worrying over the anti-ICE protests in Los Angeles and Trump’s deployment of the military to crush them. In his talk, the last, Juan Mora-Torres reminded us of a time when hundreds of thousands of immigrant workers could protest in American cities and towns without being attacked by the cops and soldiers. He told us the Chicago origins of the largest protest by workers in the United States, the May Day immigrant worker protests in 2006. That movement started the year earlier in Chicago, with a mass protest against a draconian anti-immigration bill then in Congress. Mora-Torres highlighted how the movement grew out of Mexican social networks and civil society – organizations of immigrants from particular Mexican states, soccer leagues – and thus reminded us that to really understand workers we need to be looking at the organizations they built and participated in besides unions. Mora-Torres also highlighted how the planners of the protests deliberately tied them to Chicago’s history of working-class politics, not only by picking May first as the day of the protest but by holding a rally at the Haymarket.

Author

-

Jacob Remes is a historian of modern North America with a focus on urban disasters, working-class organizations, and migration. He is a founding co-editor of the Journal of Disaster Studies, the co-editor, with Andy Horowitz, of Critical Disaster Studies (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), and a series co-editor of the Penn Press book series Critical Studies of Risk and Disaster. His first book, Disaster Citizenship: Survivors, Solidarity, and Power in the Progressive Era (University of Illinois Press, 2016) examined the working class response to and experience of the Salem, Massachusetts, Fire of 1914 and the Halifax, Nova Scotia, Explosion of 1917. He has also written scholarly articles on a variety of other subjects ranging from interwar Social Catholicism to Indigenous land rights to transnational printers in the 19th century. His popular writing on subjects relating to his research has appeared in the Nation, Atlantic, Time, Salon, and elsewhere. Before coming to Gallatin,