We have a few brief summaries of panels and papers from the Labor and Working Class History Association conference, June 2025. Mark Kagan sent his presentation in full from the session on Ruptures in Union Politics and Labor Relations in the Long 1970s. If you have a comment or summary of a panel or event from the LAWCHA conference, let us know.

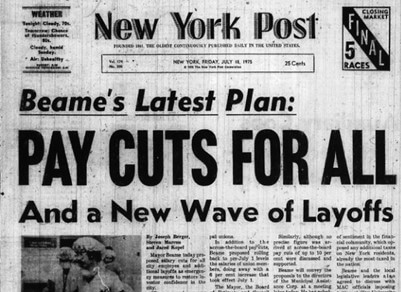

This summer marks the fiftieth anniversary of the New York City fiscal crisis – the start of neoliberalism in the United States. For most of that time, labor activists and academics have been discussing what went wrong with the labor “movement” – and what is to be done. Generally, three theories exist. As to causes, one lays almost exclusive emphasis on external political and economic circumstances, like “white flight” to suburbia before the 1975 NYC fiscal crisis, or Chuck Schumer’s passivity today. While we can and should work to change problematic or even disastrous conditions external to the labor movement itself, we can’t simply snap our fingers and get rid of Donald Trump.

The two other factors contributing to labor’s decline, though, are very much within labor’s direct control to change. What are labor’s strategic and tactical responses to those circumstances? Does it really want to get rid of Chuck Schumer? Andrew Cuomo or Zohran Mamdani? The municipal unions’ response to the fiscal crisis was to embrace risk avoidance and eventually to accommodate themselves to neoliberal austerity. In a recent article, for example, NYC and labor historian Joshua Freeman points to their continued acceptance of “pattern bargaining,” in which the city picks out a weak union to set a wage pattern, then demands the others agree to similar terms. Pattern bargaining has no statutory basis, he notes; it “survives only because the unions tolerate it.” I’d go further: municipal union leaders like pattern bargaining, because it relieves them of responsibility for the dismal contracts they have become accustomed to delivering.

Similarly ruinous was – and is – unions’ internal organization – their suppression of participatory democracy – member engagement in decision-making and policy-making. During the fiscal crisis, activists among New York’s public sector workers, under difficult conditions, and in a not wholly coherent way, wanted to fight back against concessions, layoffs and increasing management control. That demand was ultimately frustrated by union leaders, who worked hard to prevent member anger bubbling through into the type of prolonged and militant action that might have stopped neoliberalism before it became baked in.

Discouraging the development of workplace activists, initiative, voice, and agency thwarted challenges to incumbent union leaders and the labor-management cooperation schemes they adopted. It also stripped workers of the fundamental source of their power, both at times of crisis, like 1975 and 2025, or the many years in between when losses accrued at a somewhat slower rate.

Worker Resistance – Then Union Complicity

By 1975, the high point of late 1960s NYC municipal union militancy was already past. Still, union leaders were caught off guard by the suddenness of the fiscal crisis’s onset, the harshness of the city’s demands, and the anger of their members. For a time, they played a double game. Initially, they denounced any talk of concessions. A June 4 demonstration outside the corporate headquarters of Chase Manhattan Bank, demanding that banks at least share in any sacrifices turned angry, then rowdy, and was called “a very, very scary kind of experience” by financier Felix Rohatyn. Six days later, thirty thousand rallied against education budget cuts. Three weeks after that, the sanitation union nodded and winked at a two-day wildcat strike, and the city temporarily rescinded the layoffs of a quarter of that workforce. Off duty police stopped traffic on the Brooklyn Bridge, while the police and fire unions distributed a pamphlet to tourists entitled “Fear City,” denouncing layoffs of their members. Mayor Abe Beame, caught between insistent banks and union mobilizations, announced layoffs and then postponed them.

In early September, angry teachers facing ten thousand layoffs, mass reassignments, and class sizes of forty and even fifty packed Madison Square Garden. Spurning the entreaties of union president Al Shanker, they overwhelmingly rejected a tentative contract that sanctioned these horrific learning conditions, and froze wages, and voted to strike. “The mood,” the New York Times reported, “was that of enthusiasm for a fight that, the teachers said, was not for their benefit alone, but for the benefit of their pupils. Their rallying cry was lower class sizes.” Coming just a few years after the brutally divisive Ocean Hill-Brownsville strike, at least the glimmer of an alliance against austerity with parents and communities beckoned – what we now call Bargaining for the Common Good.

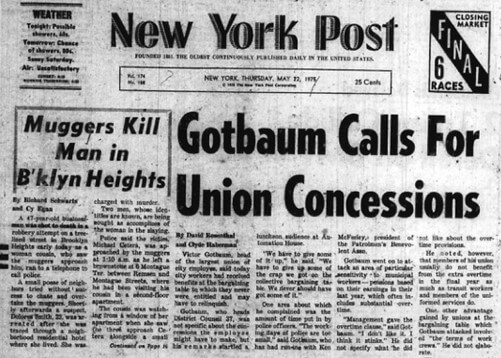

Behind the scenes, though, union leaders were negotiating capitulation. According to historian Joshua Freeman, the Chase Manhattan demonstration seemed to frighten Victor Gotbaum, the Executive Director of the white collar AFSCME District Council 37, NYC’s largest union. In May, Gotbaum, who was elected by DC37’s dozens of local presidents and therefore not directly accountable to the membership, was already publicly suggesting that some contract gains of recent years might need to be forfeited. At the end of July, he agreed to defer a recent wage hike till 1983 and pledged work rule concessions to fund health benefits. Meekly, most other unions signed on. There were no membership votes on these contractual changes, and even discussion in officer and delegate bodies was squelched. Yet the unions received no guarantees against further layoffs, which reached 20 percent of the workforce within a year.

The services that those workers provided were eliminated. That summer, the transit fare rose from 35 to 50 cents. Free higher education at CUNY was eliminated. Here was a trial run of American neoliberalism. A few years later, Robert Reich and John Donahue write, the terms of the Chrysler “bailout/rescue” were drawn from the NY example.

Now, the unions’ problem became one of managing their members’ dashed expectations. Just three weeks after the sanitation wildcat, the city renewed layoffs of sanitation workers, and, despite sporadic picketing, the union convinced its members to challenge that action (ultimately, unsuccessfully) in the courts rather than the streets. After a week on strike, Shanker reconvened a demoralized membership and chastised them. “A strike is a weapon you use against a boss that has money. This boss has no money.” Teachers narrowly accepted an even worse pact than the one they had rejected. Their lost pay and the fines levied for their illegal strike subsidized the return of a quarter of the laid-off staff — “the strike has been a tax on teachers,” the Board of Education gloated.

A month later, when union leaders agreed to load up their pension funds with municipal bonds no one else would buy, the circle was closed. Heretofore, the unions had worried that, in a default, payments to creditors would supersede those to workers and retirees; now, their retirees were the creditors, seemingly bound by self-interest to support austerity politics. In 1976, unions accepted a further two-year wage freeze. As inflation ran at 19% in 1978-79, municipal workers received a 6% raise. At DC37, 97% of members voted to accept that contract.

A few years later, Robert Reich and John Donahue wrote, the terms of the Chrysler “bailout/rescue” were drawn from the NY example.

What of the unions themselves? Three 1977 events demonstrate their institutionalization of collaboration, and the rejection of a class perspective. Beginning that January, the New York Times reported, union leaders and bankers met monthly over “coffee and doughnuts for some very private discussion of economic, fiscal and management issues facing city government… ‘I’m amused’,” said Mayor Ed Koch, “they really like each other and talk about how they attend each other’s children’s weddings.”

That spring, Governor Hugh Carey offered to amend public sector labor law to make it more like the private sector. Unions would, effectively, have gained the legal right to strike, and employers the unilateral right to change contract terms at expiration, previously forbidden. Unions rejected the offer, opting instead for defensive stability rather than offensive capability.

And that summer, the state legislature, responding to union concerns that angry workers were canceling their union memberships, legalized the agency shop, effectively allowing collection of dues from all represented workers, members or not. The editor of The Chief, New York’s civil service newspaper bluntly explained why:

An agency shop will help unions be… better able to pursue a more responsible course of action… [The Mayor’s] support of the agency shop bill was, in part, predicated on protecting the solvency of unions so they, in turn, would be strong enough to resist membership pressure… The agency shop will bring greater stability to labor management relations and will result in more statesmanship on the part of union leaders who are free from the fear of economic blackmail by their members. (Frank Prial, “Union Security: Agency Shop,” August 12, 1977; my italics.)

Transit Worker Exceptionalism? An Early Fight Against Austerity – and Moribund Union Leaders

Along with other municipal workers, transit workers also accepted a wage freeze in 1976 – but gradually their anger at both management and their own union leaders grew, eventually bursting forth in the 1980 transit strike. In the face of a concessionary union strategy, workers were able to exercise voice, and some control over their union’s path, for a time.

What made transit workers different? And why wasn’t didn’t their militancy spark more general and long-lasting resistance to neoliberalism? Here, I draw these answers – in necessarily compressed form – from the research for my forthcoming book, Take Back the Power: The Fall and Rise and Fall of NYC’s Transport Workers Union, 1975-2009 – and my own personal experiences as a transit worker.

For one thing, transit workers remembered the power of their successful 1966 strike, and substantial victories in subsequent contract rounds. They saw themselves as leaders of the NYC working-class. For another, their union president, John Lawe, was new on the job. He didn’t have the stature – or the internal control over lower-level union officers – of Gotbaum or Shanker. Finally, as Glenn Dyer notes in a new history of New York’s municipal workers, there was a long history of oppositionist movements within TWU Local 100. Rank-and-file workers had experience with the idea that sometimes you had to “fight the union to fight the boss.” Opposition coalesced around resistance to the 1978 contract which offered only a 2%-2% raise (and ultimately a 2% cost-of-living adjustment) at a time when yearly inflation was running at nearly 10 percent.

After the contract was accepted by just a few hundred votes out of 20,000 cast, dissidents set their sights on toppling Lawe in 1979 union elections – but failed to stay united. Running against three other candidates, Lawe was re-elected with just 37% of the vote. Still, dissidents held a one vote majority on the union’s Executive Board, which would have to approve the 1980 contract. They organized mass petitioning to demand MTA Chair Richard Ravitch raise their wages 30% – what they had lost to inflation, they said.

On the night the contract expired – at that time, transit workers took the mantra of “no contract, no work” seriously – the Executive Board dissidents rejected a joint Lawe-Ravitch proposal of a two-year 14% raise and took the union out on strike. Ten days later, Local 100 had wrested 22% from management. From a bookkeeping perspective, the strike looks like a decisive victory for militant politics. After all, that 8% difference paid off the cost of striking (lost pay plus fines for violating NYS’s anti-strike Taylor Law) in little more than a year and, thereafter, was substantial money in workers’ pockets forever.

Unfortunately, many transit workers came to see the strike as a defeat. The Executive Board distrusted Lawe, but left him in charge of negotiations. Then, the strike ended controversially. With dissidents demanding more than 22%, and especially amnesty from strike penalties, like those the union had won in 1966, Lawe pushed the new deal through by violating the union’s by-laws. (Talking to dissidents later, they hadn’t expected this.) Workers only voted on the contract after they were back at work. With their power diminished, there was no energy to reject and go back out.

The way the strike ended, and those fines – deducted quickly, and in large amounts, even before the raises had kicked in – demoralized workers. Gotbaum and other union leaders chimed in too, asserting that the 16% raises they now received – itself, the fruit of the strike – proved that the transit strike was a mistake. Overwhelmed by the repetition of this false narrative, most workers disavowed strike action. In 1982, Lawe and Ravitch hatched a new scheme to prevent worker resistance from re-emerging. Secretly, they agreed to a new contract full of work rule concessions. Publicly, though, they claimed that binding arbitration was necessary to resolve a host of supposed differences. Because a panel of arbitrators – including neoliberal guru Milton Friedman! – formally “imposed” the agreed-upon contract, workers were denied the right to vote on its terms.

That’s not quite the end of the story though…

Significant pockets of militant resistance to management still lingered, remaining a threat to both the Transit Authority and the Lawe leadership. In early 1984, as a new and young transit worker, I found myself working in a subway repair shop with a strong union committee, where, astonishingly to me, workers had wrested a great deal of the control of the work process from management, defying the concessions Lawe had granted two years earlier. These workers, in only a moderately strategic position – they were not train or bus operators, after all, who can directly disrupt transit service – had organized to exercise power and gain a substantial say in the running of their workplace.

Every morning, workers picked jobs by seniority, rather than have it allocated by favoritism. Foremen acted more like lead men, facilitating work and addressing problems, than domineering or abusive bosses – a very unusual circumstance in the Transit Authority – or they were set straight by slowdowns and other forms of resistance. I saw what Huy Benyon brilliantly called “factory class consciousness” looks like – direct member engagement; a belief in their own ability and responsibility to protect working conditions.

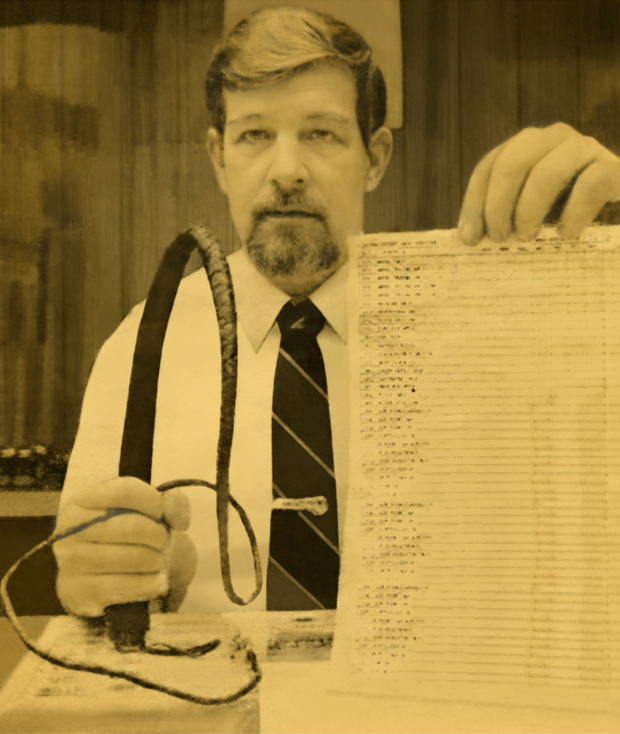

That was intolerable to a new set of Transit managers, who resolved to break workers’ power there, and wherever else it still existed. Unleashing a disciplinary reign of terror to enforce management control, they installed a psychopath – truly a psychopath, who showed off his bullwhip to a NY Post reporter and photographer – to run the shop.

Despite no help at all from John Lawe, the union shop committee organized a massive slowdown. Repairs in the shop plummeted to near zero. Over several months that created a growing crisis in the transit system, with trains repeatedly breaking down and even on fire. Workers were confident they would force management to back down.

Desperate, management suspended the union committee. As word spread, workers assembled along the central aisle of the plant, prepared to follow their suspended union leaders out of the shop. Finally, Lawe stepped in, thwarting the mass walkout with false promises that the suspensions would be reversed. Now leaderless, the slowdown gradually sputtered out; smaller defeats (with similar union sabotage) elsewhere broke transit worker militancy for almost a generation.

Risk aversion as a way of life

The decisions of Gotbaum and his colleagues in 1975, or Lawe’s betrayal of transit workers in 1980 and 1984, were born out of practices of risk aversion so familiar to those of us who study labor. Of course, even shop floor militants, or militant union leaders, need to weigh costs and benefits as they consider particular strategies and tactics. But, at the dawn of the neoliberal era, too many union leaders embraced risk aversion as a way of life.

They opted for the certainty of slowly dwindling power over risk and potential reward. They sought to resolve conflicts rather than win them, and to avoid tests of power. They trained themselves out of the boldness many of their organizations once possessed. They embraced a culture of safety, passivity and defensiveness. They prioritized the longevity of their institutions over its accomplishments. They nurtured like-minded successors and obstructed activists who yearned to fight more. Such was the Darwinian natural selection for passivity in the labor “movement.”

Quickly, and then reinforced over decades, most workers came to think of their unions as remote and mostly docile advocates, not really answerable to them in any meaningful way, and largely powerless around fundamental issues. They lost the experience of fighting management, taking initiative, acting as agents of their own destiny.

Today, the steady drip, drip, drip of worsening wages and working conditions has been replaced by the opening of a fierce onslaught. Concentration camps and terror for immigrants, attacks on the mostly unorganized working poor, and attempts to smash federal unions have come first, but it shouldn’t be hard to see that an authoritarian state will soon enough demand compliance from the remaining organizational forms of the working class.

Steven Lerner has rightly warned that “for labor, caution is fatal.” Yet most unions continue to sit on the sidelines of even the limited resistance that has so far developed, mobilizing, at best, just staff or token numbers of members. And far more will be needed than protest marches to stop Trump and his fascist offensive. We will need genuine mass disruption, the exercise of working-class power as a key part of a broader united front. The Zohran Mamdani campaign demonstrates, at least, that many New Yorkers can imagine that we can do far more than fight to protect things that aren’t good enough – that we can imagine a better possible world.

Can our union leader leopards change their spots? Perhaps some will see the urgency of the moment. Behind and below them, though, must come the mobilization of rank-and-file militants, activists, and ordinary members – pushing them forward and, if necessary, pushing them aside, so we can fight back while there is still time.