The essay related to this blog is offered free for the next three months.-Ed.

What can be learned from the past struggles to win labor rights? I hope my essay, “Illinois Teachers and the Fight for Labor Rights: A Path Beyond the Liberal Order, 1966-1984,” published in the May issue of Labor: Studies in Working-Class History, offers points to consider. The subtitle, “a path beyond the liberal order,” suggests a different way to consider the mid-twentieth century limits on labor.

The article emerged from my curiosity about the Illinois Educational Labor Relations Act (IELRA), an unusual victory for labor rights. Passed in 1984, the law brought about a sweeping statewide victory for labor, propelling tens of thousands of teachers into the labor movement as the culmination of a political battle lasting more than a decade. I wanted to understand how such a definitive labor victory was possible in the heart of the Reagan revolution. I also sought to tell the story of this victory on its own terms rather than as a blip in labor’s broader decline.

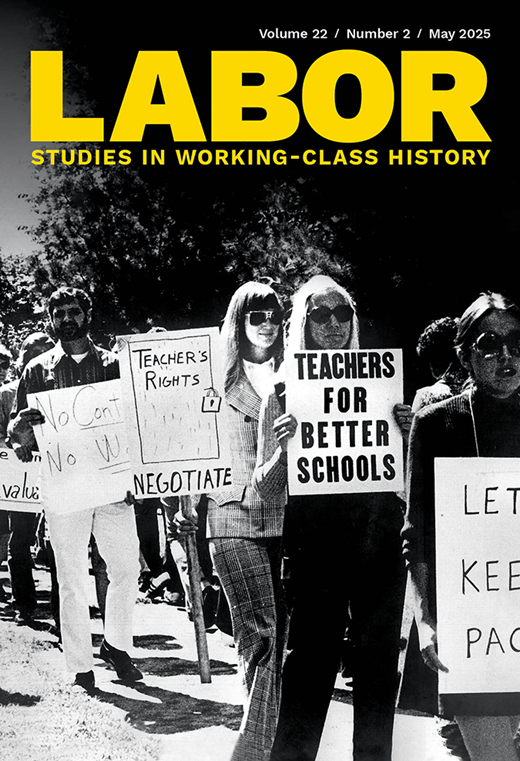

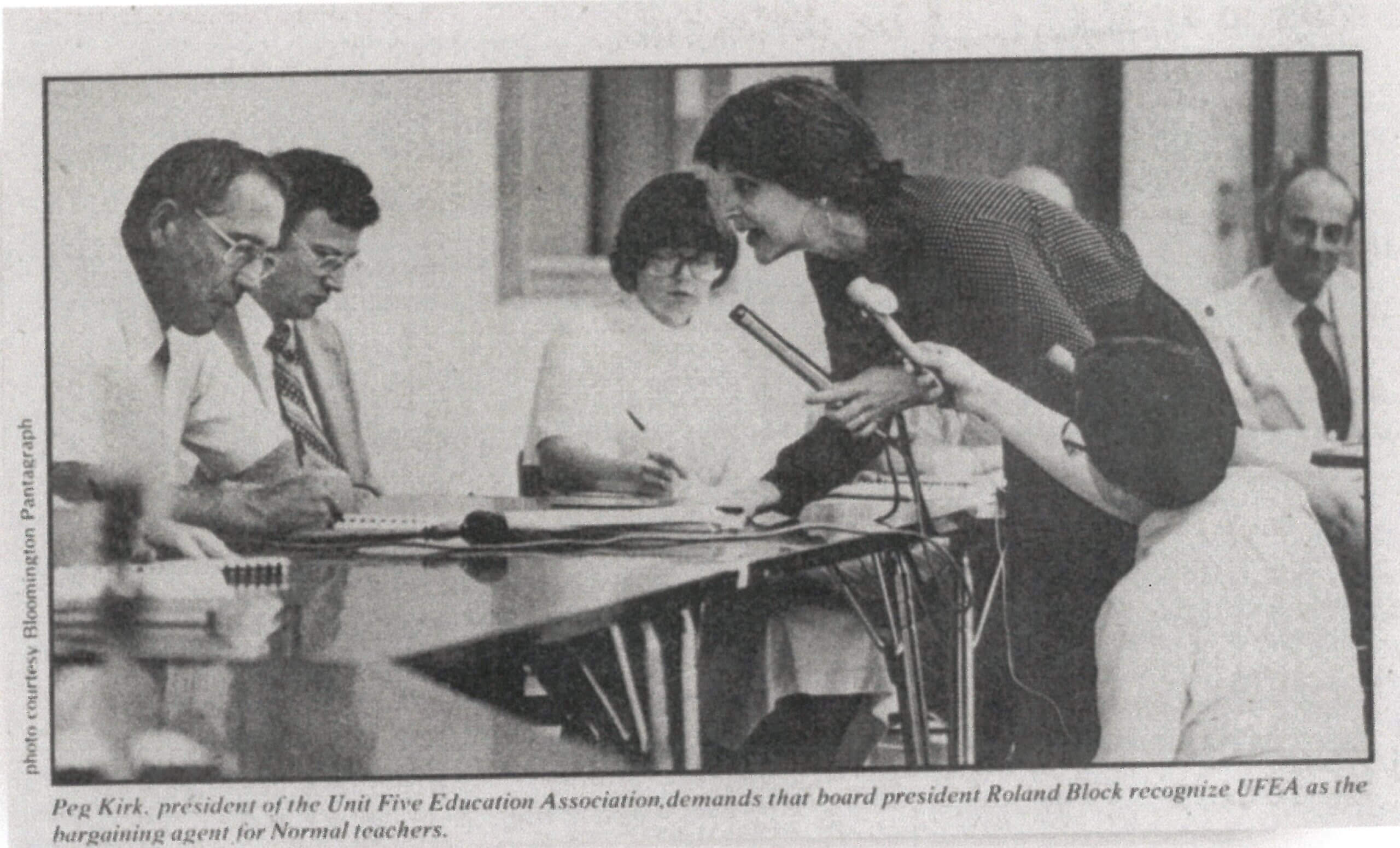

I soon found a network of strikes and school organizing campaigns that built into a teachers’ movement across the state. While much attention has been paid to the Chicago Teachers Union whose 2012 innovative campaign is more well-known, the downstate region of Illinois offers another story. There I try to trace the backstory of the remarkable resilience, militancy, and solidarity of the teachers who fought for labor rights across downstate and suburban Illinois in the 1970s and 1980s. Teachers built a political strategy based on effective lobbying across political lines and, most critically, a prolonged wave of hundreds of illegal strikes that continued through the 1970s and only escalated in the 1980s until their bill passed.

The paper traces the roots and development of this durable teacher militancy in the state. I argue that as a new generation of teachers came into the profession in the 1960s and 1970s, they drew on roots in the civil rights movement and the New Left to transform their locals and then their statewide union. Importantly, many teachers also drew on traditions of militant unionism rooted in industrial and mining communities across the state, revealing striking continuities between the rise of teachers unionism and industrial union traditions, such as that of the Southern Illinois coalfields, that have remained unacknowledged in previous historiography of teachers unions that mostly focuses on teachers’ organizing in major urban centers.

Ultimately, this article argues that the Illinois teachers movement was able to achieve its political victory in the 1980s because they rejected the framework of labor liberalism. In Illinois, Democrats had played a central role in blocking the emergence of legislation that would grant labor rights to public sector workers, recognizing that institutionalization of statewide bargaining rights would disrupt the informal channels through which Chicago Democrats maintained relationships with the city’s unions under Richard Daley’s patronage system. For Chicago teachers, this posed little issue, since they had already achieved a collective bargaining system at the pleasure of Daley’s machine. It was downstate and suburban teachers, facing arrests and injunctions when they sought to organize, who understood the need for labor protections and formed the core of the movement to win them.

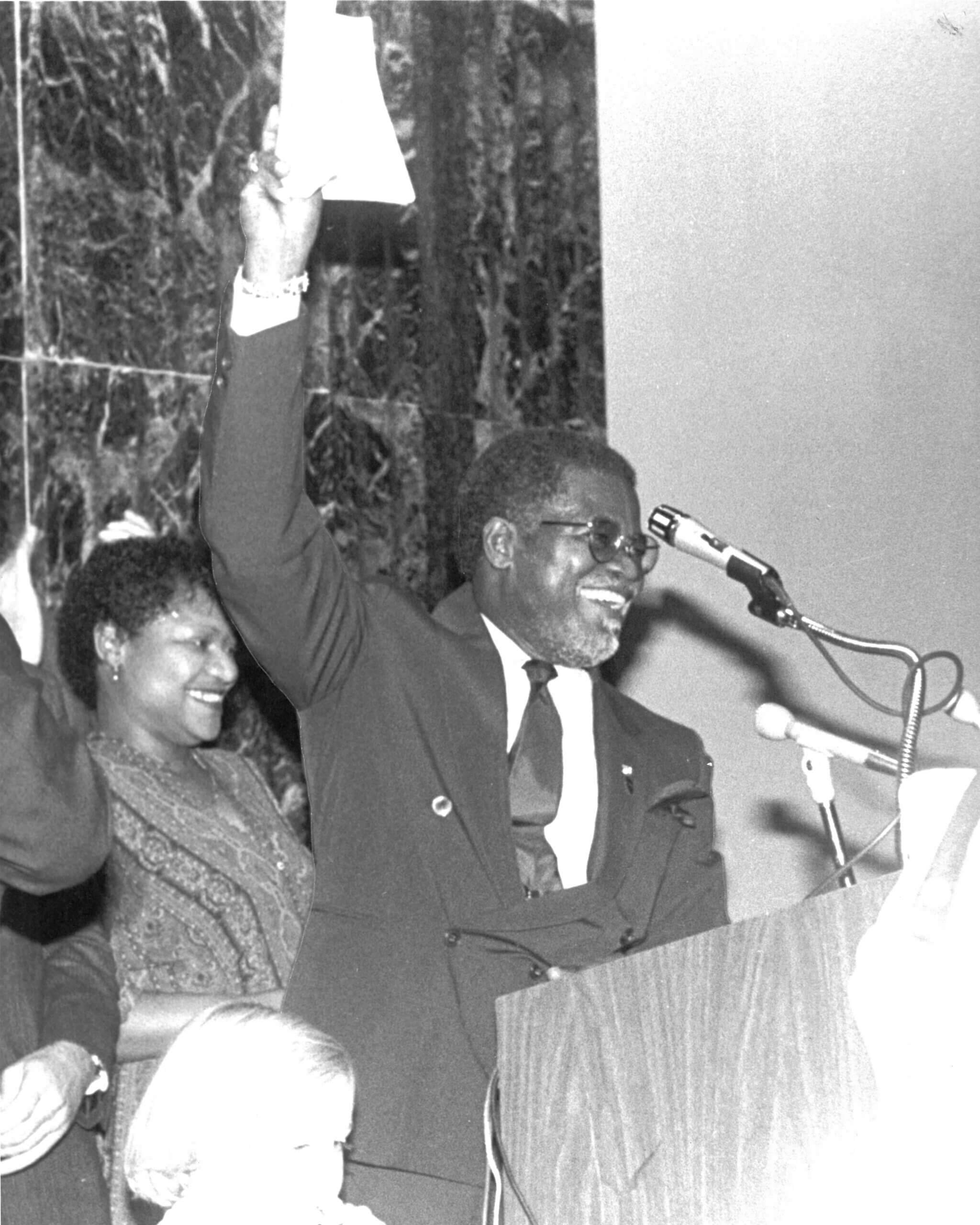

With the collapse of the Daley machine in the late 1970s and Harold Washington’s election, one could assume that the teachers’ victory represented a straightforward story of political contingency: with the decline of machine politics, Chicago Democrats became emboldened to take a more progressive position towards public sector workers, leading to the 1984 law. Instead, I argue that Daley’s patronage system and its restriction of state bargaining rights was only one formulation through which the Democratic party sought to render labor into a manageable segment of its political coalition, constraining worker militancy and political vision to do so.

This became especially apparent as I found evidence of enduring liberal resistance to collective bargaining rights even after Daley’s machine broke apart. Though I had little room to draw out its importance in my article, one striking document I found late in my research showed that Harold Washington, who is often credited with the bill’s passage, actually pushed back against the more expansive sections of the bill until it was clear how much momentum it had. Washington positioned himself as an ally to organized labor publicly. But in 1983, Washington sent a letter to Governor James Thompson encouraging him to reject the IELRA and support only the broader public-sector bargaining law backed by the AFL-CIO. Washington cited a range of issues with the IEA’s bill that made it, in his opinion, too aggressive and transformative. He objected to the bill’s omission of a management rights clause, to its inclusion of part-time and temporary workers, and to the regulatory powers it vested in officials outside of Chicago. This, I think, is convincing evidence of how movements from below matter. Finding this document, it became impossible to view the passage of the IELRA as a simple story of transition from the corruption of Daley’s machine to his more progressive successor. The downstate teachers’ movement created the pressure needed to push the bill and ensure it remained as expansive as possible, up until the moment of its passage. I’ve included Washington’s letter below.