In his recent executive order on “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” President Donald Trump criticized historians for “replacing objective facts with a distorted narrative driven by ideology rather than truth.” In a subsequent order he called for the elimination of “radical indoctrination” by history teachers in K-12 schools and demanded it be replaced by a patriotic curriculum that celebrated American greatness and achievements. He has also increasingly tried to force his patriotic version of American history on colleges and universities by gaining more control over the accreditation process and threatening to withhold funds from those universities that continue to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in either their curriculums or their admissions and disciplinary policies.

American historical associations have responded quickly to Trump’s executive orders and have argued that he is the one who is trying to censor history to serve his own ideological agenda by forcing history teachers to ignore negative aspects of U.S. history such as slavery. The Organization of American Historians, for example, responded to Trump’s orders by noting that “This is not a return to sanity. Rather, it sanitizes [history] to destroy truth.”

Labor historians should be particularly concerned about Trump’s misuse of tariff history because his tariff policies remain popular with many working-class voters and labor union leaders despite the recent economic meltdown they have caused.

Although historians have devoted significant attention to Trump’s efforts to impose a patriotic form of history at all levels of the educational system, they have spent less time examining how Trump has repeatedly used U.S. tariff history to defend his own tariff policies. Yet much can be learned from this application of history to his agenda. Articles published in the popular press have pointed to the egregious factual errors in his accounts of tariff history. But more troubling from a historical perspective is his almost total neglect of changing historical contexts. Inattention to context in turn leads him to misunderstand basic issues of cause and effect. Labor historians should be particularly concerned about Trump’s misuse of tariff history because his tariff policies remain popular with many working-class voters and labor union leaders despite the recent economic meltdown they have caused. Three examples will suffice here.

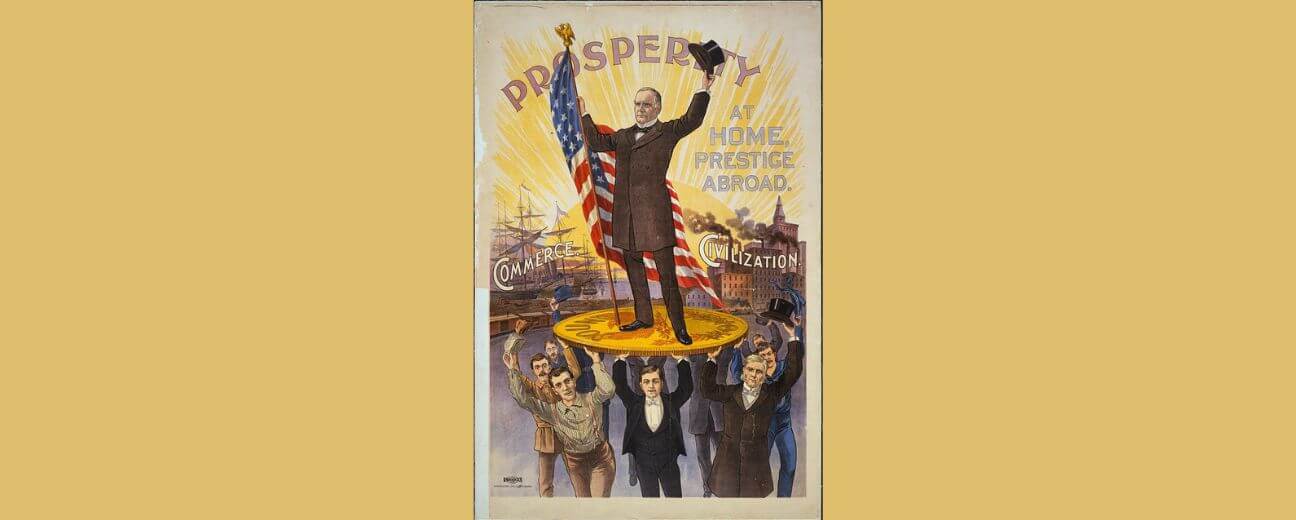

President Trump’s favorite historical narrative has emphasized the ways in which high tariffs helped Republicans achieve unprecedented levels of national prosperity during the Gilded Age. The primary hero of his narrative is William McKinley who, as a congressman, proposed and helped to pass legislation in 1890 enacting high tariffs and subsequently ran successfully for president on a high tariff platform. Trump has argued repeatedly that “McKinley made our country rich through tariffs.”

Yet there is clearly another side to the story often detailed in the history textbooks Trump so detests. Prosperity during this era was mostly limited to the new Robber Baron class of corporate leaders. Most industrial workers lived in poverty despite working long hours in notoriously unsafe factories, mines, and mills. Children as young as ten were increasingly employed in industry because they were the cheapest labor force and could be easily exploited. These deplorable conditions spawned militant strikes that were defeated only when private detective agencies or state militias violently intervened, as happened during the Homestead Steel Strike of 1892. So high tariffs did not translate to prosperity for industrial communities.[i]

Family farms experienced equally tough conditions, as “bonanza” farmers in the Midwest easily acquired expensive new machinery that allowed them to more efficiently plow larger fields and to dominate agricultural markets. They also gained cheaper rates for shipping their products on the railways. In protest, family farmers launched a left-wing populist movement far different from Trump’s right-wing populism. Populists in the 1890s advocated for nationalization of the rail lines, a more flexible currency, and a publicly run subtreasury system that would provide interest-free credit for farmers during the growing season.[ii]

A major depression occurred in 1893 and helped convince many corporate leaders that the country had a problem with overproduction. Workers and farmers, by contrast, emphasized that the problem was one of underconsumption; they lacked sufficient wages to buy the exciting new products being produced by factories. As president, McKinley sought to solve the problem of overproduction by increasing export markets rather than improving conditions and wages for working people.

So, despite running on a high tariff platform, McKinley devoted himself to seeking increased exports through negotiations with trading partners that reduced tariffs

So, despite running on a high tariff platform, McKinley devoted himself to seeking increased exports through negotiations with trading partners that reduced tariffs. Historians argue that McKinley engaged in imperialism during the Spanish-American War to acquire the Philippines and Puerto Rico as vital links to secure trade routes to China and South America. [iii]

Trump’s omissions in his Gilded Age narratives reveal the narrow lenses through which he views national wealth: only the people at the top of the socioeconomic ladder matter, despite his political rhetoric to the contrary. A broader approach to the Gilded Age demonstrates that tariffs were unsuccessful in bringing widespread prosperity or even economic stability. Political leaders, frightened by growing social unrest, instead moved increasingly toward exports, and the acquisition of some imperial outposts, to solve the problem of overproduction.

Another of Trump’s historical narratives emphasizes that a lack of tariffs caused the Great Depression of the 1930s. But this narrative is factually wrong. Although Democratic President Woodrow Wilson successfully implemented an income tax and reduced tariffs in 1913, Republicans resumed control of the presidency in 1921. They imposed high tariffs with the Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922, which remained in effect throughout the decade. Even higher tariffs were implemented in 1930 with the Smoot-Hawley Act, which historians argue caused a reduction in international trade that worsened the Great Depression.

Strangely, in his most recent speech about the Great Depression and tariffs, Trump seemed poised to discuss Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs but instead grew distracted and rambled about the ramp system that had been developed in the White House to accommodate Roosevelt’s polio-induced disabilities. Yet it was the extension of New Deal programs, as well as the increased safeguards which they guaranteed to the labor movement, that decreased economic inequality and brought about more broadly shared prosperity to the United States in the post-World War II era.

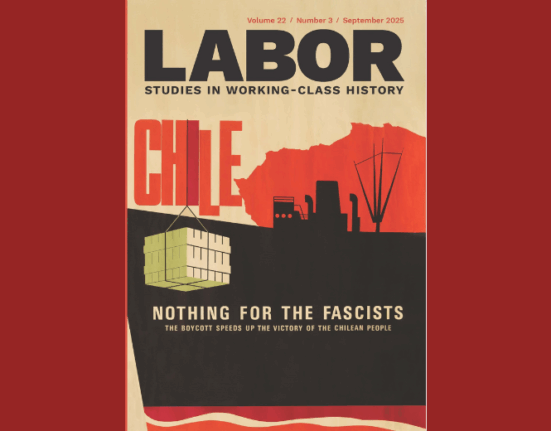

A third historical narrative frequently employed by Trump is that the North American Free Trade Agreement of the 1990s led many corporations to close their factories in the United States and move them to Mexico where they could employ workers at lower wages. This narrative is appealing to many Americans because it is at least partially true and is part of the lived experience of several generations of Americans. Doubtless many are reminded of the loss of good paying jobs when traveling through the small mill towns of the Northeast or the factory towns of the Midwest and South, where abandoned manufacturing plants and equipment still dot the landscape. Trump has claimed that NAFTA cost the United States 90,000 factories. Other studies place the loss of factories at around 70,500.

The bigger issue, as with Trump’s rendering of the Gilded Age, is that of historical context. After World War II, the United States increasingly relied on a free trade model in guiding its foreign policies with other countries. These policies made sense because the United States emerged from the war economically far stronger than its closest economic competitors and could dominate foreign markets as well as its own internal markets.

Yet, in contrast to the Gilded Age or the 1920s, the United States also assumed more responsibility during the post-World War II era for maintaining the health of the international capitalist system. During the late 1940s, for example, the United States gave extensive aid to Europe through the Marshall Plan to help it recover from the war. The United States also helped to rebuild the Japanese economy during its military occupation of that country. In 1961, the United States created the U.S. Agency for International Development to help eradicate poverty in poorer countries around the world. U.S. aid programs during the Cold War were not simply altruism, or giveaways, as Trump has insisted. They were designed to thwart Communism and build new export markets for American products. Arguably, these economic initiatives proved cheaper and more successful than U.S. military and covert interventions designed to stop the spread of socialism or communism during the Cold War.[iv]

U.S. history since 2000 suggests that neither tariff nor free trade models are the best means of assuring American prosperity in an increasingly globalized system of capitalism.

By the 1970s, however, U.S. economic prosperity was threatened by the re-industrialization of Japan and Europe and by the desire of American corporate leaders to lower labor costs by moving their businesses to poorer countries. The runaway plant movement predated NAFTA but drew strength from it. U.S. history since 2000 suggests that neither tariff nor free trade models are the best means of assuring American prosperity in an increasingly globalized system of capitalism. Instead, a hybrid model of economic development is necessary. Trump’s tariff increases during his first term led to a net job loss rather than job growth. The green economy initiatives of the Obama and Biden administrations proved more successful in creating new jobs and should be a key underpinning of future growth. This should include significant federal subsidies, as outlined in the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act, to repair and update the aging mass transportation infrastructures of the United States in ways that are environmentally friendly.

As economists have suggested, the United States should also work to further capitalize on areas in which it has developed new strengths since NAFTA such as the tech fields and biomedical innovation. This, however, will require restoring some of the research grants to federal agencies and to universities that Trump has recently eliminated. Efforts by Congress to regain some control over tariff policy also seem critical to ensuring that the needs of multiple economic stake-holders are addressed.

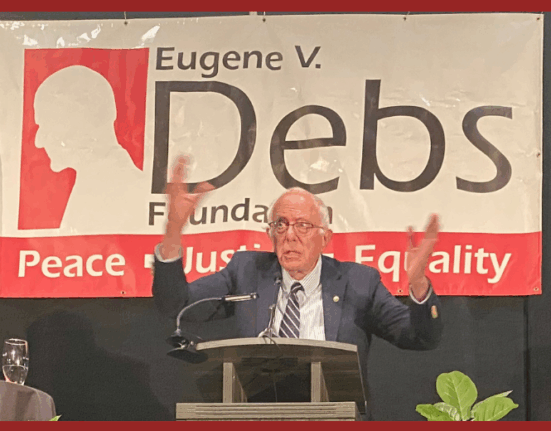

Senator Bernie Sanders has recently attracted large crowds by emphasizing that labor standards need to be considered in tariff decisions. He suggests the need for targeted and limited tariffs to penalize low-wage countries led by authoritarian leaders but the pursuit of “fair trade” with allies whose labor standards are roughly comparable to those of the United States, or who are striving to improve labor standards.Ironically, one innovation of the United States-Mexico-Canada Free Trade Treaty (USMCA) signed by Trump in his first administration might prove useful in further advancing these kinds of labor goals. AFL-CIO leaders and Democrats in Congress successfully lobbied the Trump administration to include an impressive Labor Charter in the treaty that requires the three signatories to meet fair labor standards established by the International Labor Organization. It also created a mechanism for monitoring labor standards in each country and developed a hotline for reporting violations. Although only used occasionally since the treaty was ratified, this visionary framework seems to provide a more promising way for current labor leaders and labor supporters to ensure the growth of well-paying jobs in North America than Trump’s fairy tale efforts to create a second Gilded Age. By isolating the United States from the global economy and eliminating the New Deal-inspired social welfare programs that have uplifted the standard of living in the United States for generations, Trump will instead create a new nightmare for working people.

[i] See for example, Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty: An American History 6th ed. (New York: 2020) 590-676 and https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/programs/child-welfarechild-labor/child-labor/.

[ii] Foner, Give Me Liberty, 614-647.

[iii] See especially, Thomas McCormick, China Market: America’s Quest for Informal Empire, 1893-1901 (Chicago, 1967).

[iv] Thomas McCormick, America’s Half Century: United States Foreign Policy in the Cold War and After. 2d. ed. (Baltimore, 1995); https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Agency_for_International_Development.