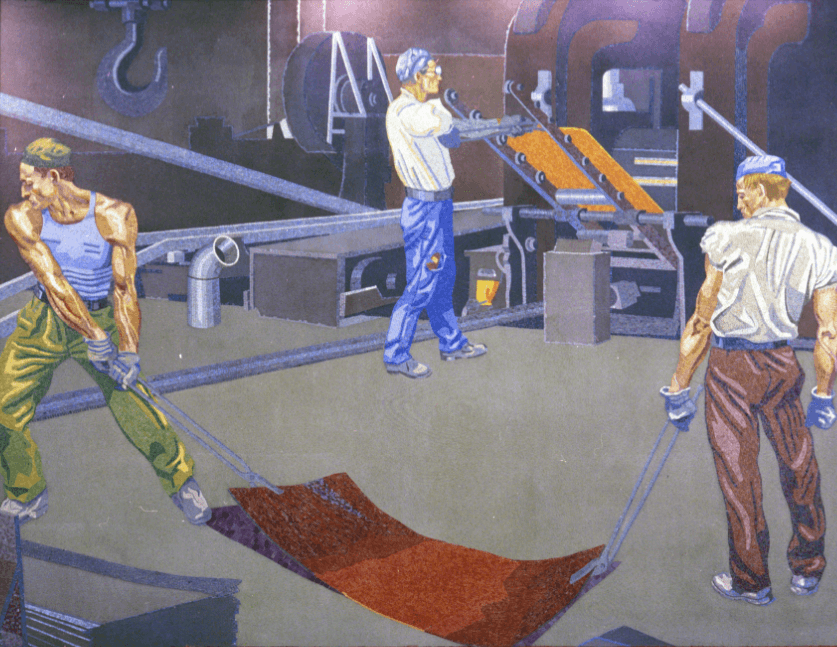

When the Cincinnati city government decided in 1930 to build a large new rail station, they chose German immigrant artist Winold Reiss (1886-1953) to decorate parts of the interior with sixteen large 20’ x 20’ mosaics—murals, really– depicting the principal industries of the area. Not only did Reiss accomplish this with real artistry, but he depicted workers at labor in each mosaic.

Both before and after the Civil War, Cincinnati, with its extensive river boat and rail network and a major influx of German immigrants, served as a major regional industrial hub in the near Midwest. Important early industries included pork processing, foundry work, beer brewing and furniture manufacture. Thanks to Reiss, we still have a public record of the many tasks carried out by workers in the Queen City’s major industries of the 1930s. He based many of his labor portraits on photographs he took of the area’s surrounding plants.

Railway Age 94 (April 23, 1933), p. 581.

Reiss was born in Karlsruhe, Germany, trained in Munich before World War One, and immigrated to the US in 1913 where he initially worked in New York City. During the 1920s he traveled several times to the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana and produced a number of paintings based on the lives of the Native Americans living there.

The Cincinnati rail station that once housed the murals is now called Union Terminal and has gone through several changes with the decline of rail travel – now serving instead as the home of three] museums. Reiss’s original mosaics have been moved and preserved in several locations around the city and some images are still available on the web. Until recently they have been displayed at the downtown Cincinnati Convention Center, and will be returning there following renovations of that building.

The mosaics depict myriad area industries, including pork processing, piano building, paint manufacture, soap, machine tools, aircraft, drugs and aircraft manufacture. A few of Cincinnati’s large enterprises from its industrial heyday with many women workers, such as garment, shoe manufacturing, and typesetting have been left out – but overall the mosaics include a wide-ranging survey of the variety of industrial establishments on the eve of the Great Depression. Two of the murals are based on the artistic pottery of Rookwood, a woman-owned business that did employ many craftswomen.

Photo by Thurman Wenzl

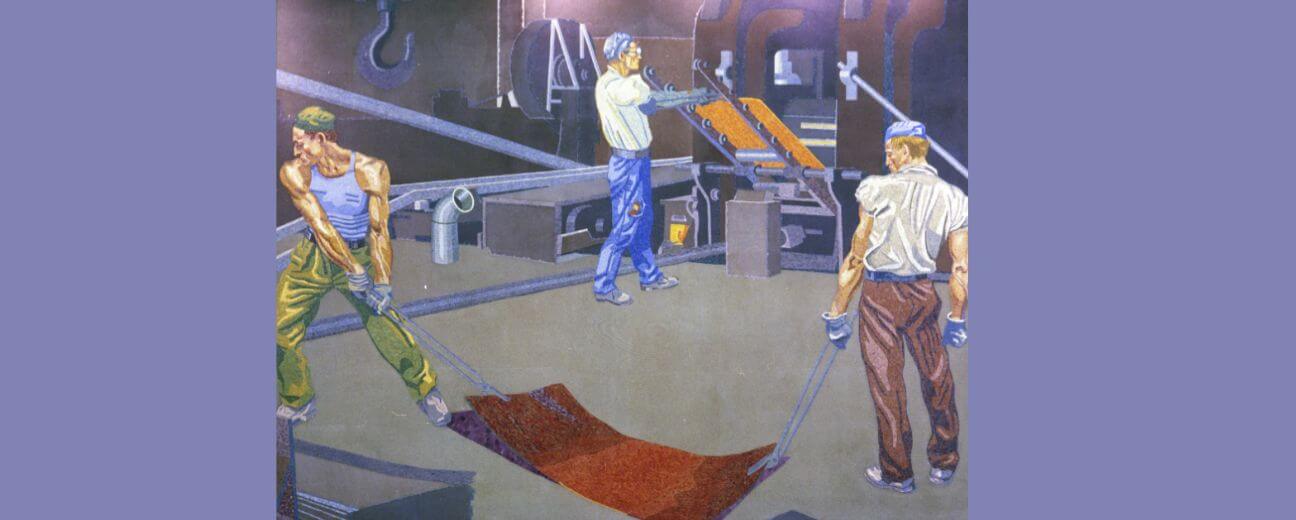

There are no explicit references to worker organizing among the mosaics, but one image of workers struggling with steel sheets which would become corrugated siding, is set at a steel mill in Newport, Kentucky (just across the Ohio River from Cincinnati) where 2500 workers seeking representation with the Amalgamated Association struck in 1921. This strike had major community support, so strong that neighborhood women near the plant would only allow bread deliveries if the driver could show a Teamsters card. Sadly, the strike was lost after several months, despite efforts by Kentucky’s Governor to persuade the owners to negotiate with the workers.

Public domain.

As of early 2025, only five of Reiss’s mosaic-murals are on display. They can be found in the public areas of the Cincinnati airport, across the river in northern Kentucky. The remaining murals depicting the bygone world of working-class Cincinnati are expected to be installed in the downtown Duke Convention Center when the building’s reconstruction is completed in 2026.