Jesse Chanin’s book Building Power, Breaking Power: The United Teachers of New Orleans, 1965-2008, published earlier this year, tells the remarkable story of the United Teachers of New Orleans (UTNO), a teachers union that defied expectations, labor factionalism, and racial divides to become a powerhouse in Southern organized labor and New Orleans politics. The book traces the union’s victories and potential in the second half of the twentieth century. It concludes with the union’s decimation in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, a devastating example of disaster capitalism at work. I interviewed Chanin about this revealing book.

What led you to researching the United Teachers of New Orleans (UTNO), and what was your motivation behind Building Power, Breaking Power?

I taught in public schools for five years in New York City and then I moved to New Orleans in 2012 and worked in and around schools in various capacities. I was a little shocked by what I saw in some of the charter schools, specifically in terms of how students and teachers were treated. I should mention that all the schools I worked in have since changed management organizations or shut down. So when I went to graduate school in 2015, I thought I wanted to do some sort of study about the charter schools, maybe focusing on exclusionary discipline or the treatment of students with exceptionalities. However, I felt very negative about what I had experienced, and I didn’t want to spend five or six years just criticizing what was happening.

When I thought more about my experience in NYC, I realized that I’d had so many more rights and freedoms as a teacher there than the educators I saw here in New Orleans. I had taken the union for granted when I was a teacher in New York—I was right out of college and wasn’t really thinking about a pension or benefits. But the little things that make all the difference in a teacher’s quality of life—duty free lunch, being paid for after school meetings, planning time during the day—seemed sorely missing in the schools I visited in New Orleans. I think the overworking and mistreatment of teachers in New Orleans played a significant role in the negative ways they were sometimes interacting with students.

Activists and veteran teachers told me that New Orleans had had a strong teachers union before the storm, so I began to investigate UTNO and its history. As I learned more, I was shocked that more people working in the schools didn’t know about UTNO, or even had accepted narratives claiming that the union (or its alleged corruption) had been a big part of the reason the New Orleans schools were “failing” before Hurricane Katrina or “had to be taken over.” I was excited to research UTNO for my dissertation both to give more nuance to the community’s ideas about the union (and the pre-Katrina schools), but also because it’s primarily a story of victory and strength. Even though UTNO was eviscerated after the storm, I think UTNO’s story shows what’s possible, and the ways in which struggles for economic and racial justice can be successfully combined to create meaningful change that, at times, even transcends the education sector.

That dissertation, of course, became Building Power, Breaking Power. I tried to write in an accessible way, and let the educators tell the story in their own voices as much as possible, so that teachers today could read the history and perhaps see themselves in its pages, or in pages yet to be written.

The UTNO clearly provided a powerful foundation for labor to build its strength and advance a political vision in New Orleans and Louisiana more broadly. Though the union eventually collapsed, it remained durable through the second half of the twentieth century. Does the history of the UTNO complicate our understanding of Southern labor history, and the possibilities or limitations to organizing Southern workers?

UTNO is an exceptional union, and I think we often have the temptation to frame New Orleans history as exceptional, which is true in many senses, but can also obscure the ways in which similar dynamics are often at play across other southern cities. Certainly, there is a long history of organized labor in New Orleans. I’m thinking of Arnesen’s book on the dockworkers (Waterfront Workers of New Orleans), the 1892 General Strike, or a recent exhibit here, by the New Orleans Workers’ Center for Racial Justice, that highlighted worker struggles across sectors, from musicians to domestic workers to hospitality.

Louisiana had a powerful statewide labor organization before UTNO, but it was largely dominated by white men and had a pugilistic reputation. For example, one teacher told me that when she went to the Louisiana AFL-CIO conference as an UTNO member, her father said, “Oh my goodness, my daughter is going to be with the mafia!” But the AFL-CIO (and its longtime president, Victor Bussie) was effective. For example, from 1955-1976, Louisiana was the only southern state without right-to-work legislation on the books. UTNO won collective bargaining in 1974. So the teachers really entered the scene as private sector unionism in Louisiana began its decline and they did so representing a totally different constituency: Black women.

In the 1970s, there was a wave of teacher organizing across the country. I recommend Jon Shelton’s book on this topic, Teacher Strike! According to Shelton, in the 1975-76 school year alone, there were over 200 teacher strikes in the United States, many of them lasting months. UTNO was part of this wave, and at the time it seemed like perhaps teachers across the South would join their peers across the nation in winning collective bargaining. By and large, that did not happen. There were certainly moments of struggle, and I mention some of those in the book: the Memphis “Black Monday” protests in 1969, the Mississippi wildcat teachers strike of 1985, the Alabama Education Association’s protests to save school funding in 1971. But aside from Florida, where public sector workers earned the right to collective bargaining statewide, there are very few examples of powerful teachers unions across the South besides UTNO.

Lane Windam’s book, Knocking on Labor’s Door, demonstrates how, in the private sector, the lack of collective bargaining agreements across the 1970s doesn’t reflect that workers weren’t trying to organize. But they were being met with incredible counteroffensives, hostile laws, and repression. I imagine that’s true of teachers across the South as well.

But UTNO was successful—they were the largest local in the state by the 1990s. Partially that’s because of luck, good timing, and the support of the Black political machine in New Orleans. But it also shows how education can be a bipartisan issue. For example, UTNO’s organizing galvanized the sector and led to collective bargaining agreements in much more conservative neighboring parishes, some of which are still in place today. And the dismantling of UTNO, the firing of the educators post-Katrina—though supported by conservatives, was actually led primarily by business-friendly democrats who wanted to demonstrate the power and efficiency of an all-charter district. In fact, the architect of the New Orleans charter makeover, Leslie Jacobs, was endorsed by UTNO when she ran for Orleans Parish School Board in 1992.

All of that is to say—I do think UTNO shows that there is great potential for organizing educators in the South. And I think that we need to think of collective bargaining agreements as a very powerful tool, but only one of many possible positive outcomes of teacher organizing.

Does the history of the UTNO help us understand the relationship between the civil rights movement and organized labor?

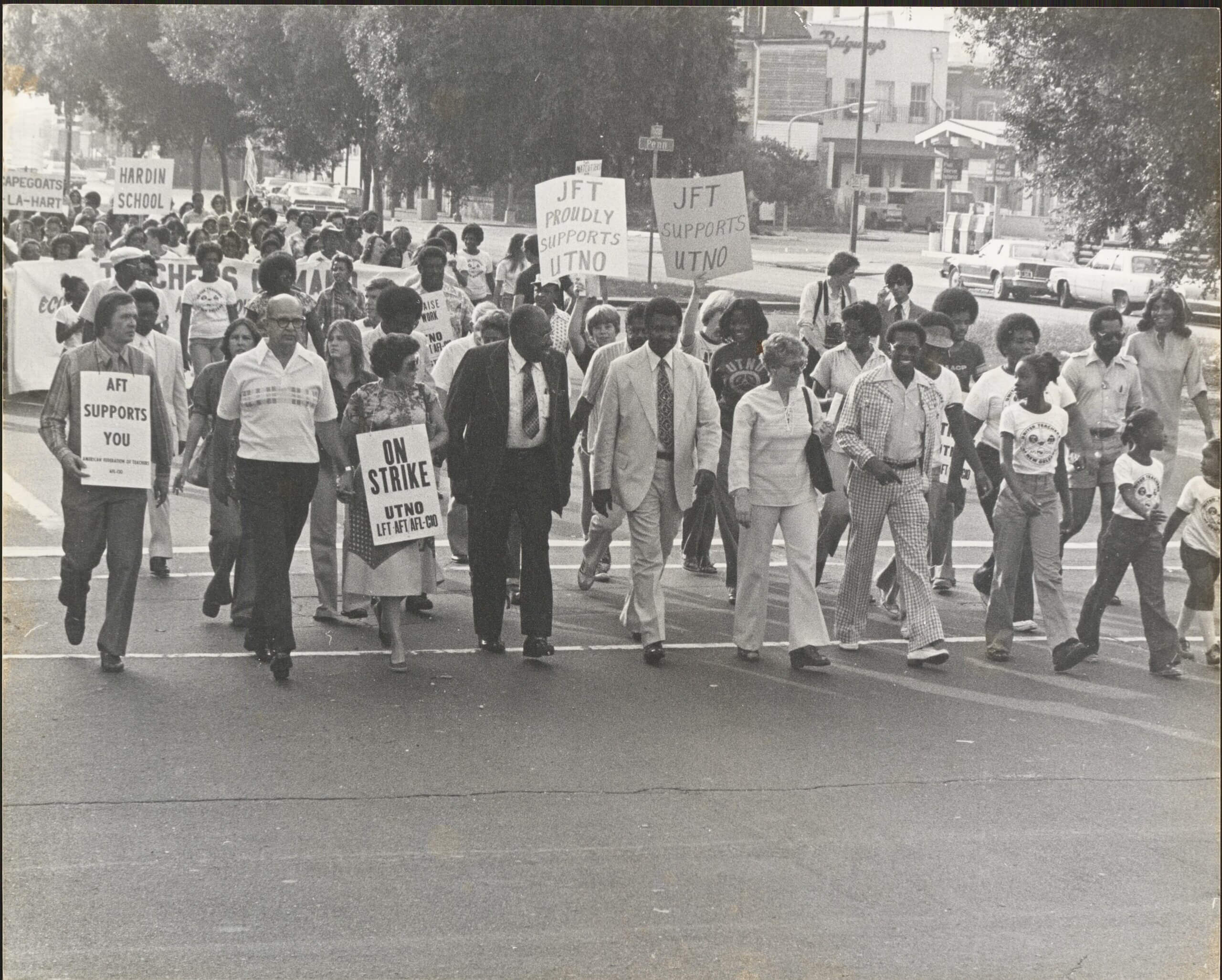

Organized labor was integral to the civil rights movement (look at the Memphis sanitation workers strike, for example; or William Jones’ excellent book, The March on Washington) and workers’ rights remain at the forefront of struggles for dignity and equity for people of color across the country. In New Orleans, the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) Local 1419 had long supported civil rights goals, allowing groups such as the Congress of Racial Equality and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to use their meeting hall, and speaking out against segregation. The ILA also allowed Local 527 (before they became UTNO in 1972) to use their meeting hall and ILA leadership came out to support UTNO’s strikes and job actions. Civil rights and labor rights went hand in hand for the Black community in New Orleans.

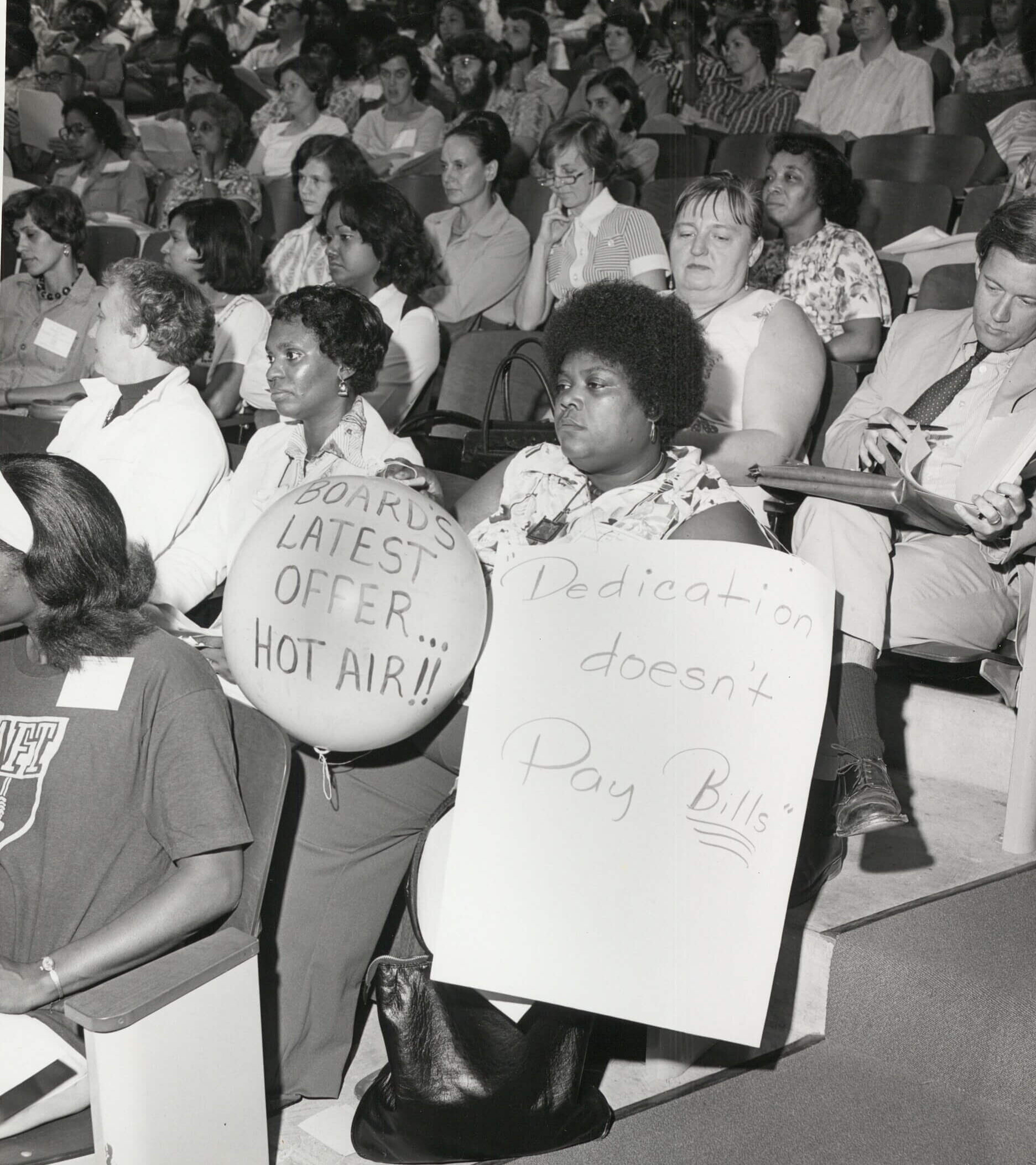

Local 527’s early protests were advocating for labor rights and civil rights in tandem. For example, when they went on strike in 1966—the first teachers’ strike in the South—they demanded collective bargaining for teachers as well as the hiring of Black supervisory, clerical, and maintenance staff, and more Black bus drivers. They also advocated on behalf of Black parents and students who were mistreated during the integration of the New Orleans schools. The leadership of Local 527 obviously saw their fate as deeply connected to the fate of the larger Black community.

Several UTNO members were civil rights movement veterans, and the union took strategies and tactics from the civil rights movement into their labor organizing. For example, they prioritized strikes and protest, and uplifted democratic decision making. While white UTNO members told me that participating in strikes was “Just so scary,” a Black UTNO member recalled, “Crazy as it may seem, we had a lot of fun and some of us were really just sad that the strike had ended.” Black educators were used to strikes and protest, used to risk, from their time watching, or participating in, civil rights actions. UTNO’s militancy was possible because of its connections to the civil rights movement.

Finally, UTNO’s successes, particularly in the 1960s and early 1970s, were seen by the Black community as civil rights successes. For example, the Louisiana Weekly, a Black-run newspaper, wrote an editorial strongly supporting UTNO’s collective bargaining campaign. Activist Black pastors joined the union on the picket lines. Public school parents joined educators in singing “We Shall Overcome” and other civil rights standards at a school board meeting. Later on, UTNO was the hub for the New Orleans branch of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, which did voter registration and outreach in Black communities.

As Jacquelyn Dowd Hall points out, if we think of the civil rights movement as existing only in the 1950s and 1960s, we miss both the Black labor rights organizing that took place in the 1940s and the rise of Black-led public sector organizing in the 1970s.

New Orleans teachers connected their organizing to a broader strategy for community empowerment and support. What are the implications for the history of teachers’ unions? Does your history contextualize the history of bargaining for the common good, typically attributed to the Chicago Teacher Union’s 2012 strike?

In 1968, there was a high-profile strike by the United Federation of Teachers in New York City that was widely perceived to be white teachers prioritizing their own self-interest over the needs of mostly Black and Latino schoolchildren (see The Strike That Changed New York by Jerald Podair). The strike shut down the school district for several weeks and destroyed the Black-run experiment in community-controlled schools in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, Brooklyn.

The UFT is not the only union that was accused of prioritizing the interests of its (mostly white) members at the expense of children of color. Similar dynamics were at play in strikes in Newark, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Detroit. Though the national American Federation of Teachers (AFT) supported the civil rights movement and, for example, sent teachers to participate in Freedom Summer of 1964, white flight from urban areas (and Black migration from the South) resulted in a public school population that was often much more diverse than a city’s teaching force in urban areas across the northeast and west. And unions lagged in hiring teachers of color. Middle class teachers perhaps did see their interests as divergent from the interests of the communities they served, which became largely mired in poverty as urban divestment continued through the 1970s.

UTNO mostly avoided this problem. UTNO formed from Local 527, a segregated Black local, and prioritized Black leadership. As I described above, they emerged from the civil rights movement and saw civil rights struggles, insofar as they impacted the schools, as their purview. For example, when the district announced a plan for faculty desegregation, UTNO got involved to ensure that no Black teachers or principals would lose their jobs. They supported Black students who walked out at a local high school to demand revisions to the disciplinary code and Black history classes. They fought for more funding for public education and opposed budget cuts. They demanded democracy and transparency in the schools. These struggles were important to UTNO’s membership too.

I think the history of the UFT and other similarly situated unions makes it seem like “bargaining for the common good”—that is, understanding the interests of teachers as inherently connected to the interests of students and families—emerged in 2012. There certainly have been some innovative and progressive strategies that came out of the 2012 Chicago teachers strike or the big Los Angeles strike in 2019 or the 2018 “Red for Ed” movement. I would argue that the history of those strategies, or the precedent for them, can be found much earlier in teacher unionism. UTNO is a great example, but so is the Teachers Union in NYC, a progressive precursor to the UFT that was dismantled during the Red Scare. I think that organizers today could learn a lot from looking at the past, especially from Black-led unions that were operating in largely hostile territory, like UTNO.

Your book ends with crisis: the devastation of Hurricane Katrina provided the perfect disruption for neoliberal policymakers to finish off New Orleans’ public school system and its union by switching to charter schools. How did the city arrive at such a dire moment?

By the 2000s, UTNO was definitely a target. As I mentioned, it was the largest local in the state, and it was pretty effective at representing a constituency that was largely Black women. Though there were other powerful groups in the city, UTNO was a core part of the Black political machine in New Orleans. Conservative state lawmakers wanted to take over the district (I recommend Domingo Morel’s book Takeover on this topic). Business interests wanted to introduce charter schools more widely. The Catholic Archdiocese had been trying for decades to get a private school voucher program passed. And the schools had been divested from for years. They were generally performing poorly on tests, they couldn’t keep a superintendent, and the district was in financial trouble.

UTNO wasn’t letting any of those groups actualize their visions. They repeatedly blocked voucher bills by adding an amendment that said schools that accepted the vouchers would have to give their students the state tests, which the archdiocese refused to do. They stymied the spread of charters by requiring that a school could only be converted into a charter if 75% of the school’s teachers and parents agreed. And they fought against the privatization of school support workers, such as maintenance workers, bus drivers, and cafeteria workers—all of whom had “me too” contracts, so they got raises whenever UTNO educators did.

Then Hurricane Katrina hit and powerbrokers and policymakers saw an opportunity. The union was scattered across the country—remember, people couldn’t return to the city for weeks or months after the storm hit—and the architects of the new charter school plan took advantage of that. The push to make New Orleans an all-charter district, to fire the displaced educators, and to remove local control over the schools occurred at the local, state, and national levels and in both the public and the private sectors. For example, the federal government offered the state $20.9 million in educational disaster aid—but only to open charter schools. The state government seized control of the schools (by lowering the grade that counted as failing such that 102 of the city’s 117 schools were deemed “failing”) from the local school board. The board, having lost most of its schools, fired all its teachers, approximately 7,500 educators. The teachers learned they were being fired on November 30, 2005, just three months after Hurricane Katrina hit the city. New Orleans still did not have a single, open public school at that time.

It’s a textbook example of Naomi Klein’s concept of disaster capitalism. In the wake of the storm, while people struggled to recover, policymakers and leaders dismantled the public school system and replaced it with a “portfolio model” of charter schools. The state slowly phased out all their direct-run schools until, in 2019, New Orleans became the nation’s first all-charter district.

The UTNO never recovered after Katrina, and New Orleans schools remain charter today. How does its story square against the broader “declension narrative” of US labor history? Is the UTNO a victim of an inevitable decline under neoliberalism, an exception, or something else?

We have one direct-run school that opened this year! So New Orleans is no longer an all-charter district.

I argue that policymakers could not have created the charter school district in New Orleans without the impact of the storm. Though UTNO may have been weaker in 2005 than it was in, say, 1978, since the labor movement nationally was weaker, and the union had become a little more bureaucratic and less militant, UTNO remained a powerful force both locally and in state politics. So I don’t think its decline was inevitable, but rather was a product of bad timing and disaster capitalism. I haven’t talked much about democracy, but UTNO was very committed to a democratic structure, and prioritizing rank and file leadership, and I think that was part of its undoing after the storm. But that was also part of its vibrancy. Unlike many other teachers unions, UTNO held a powerful (and successful) strike in 1990 and remained committed to protest as a core tactic. A narrative of slow decline does not accurately describe its trajectory.

I should also say that UTNO is still around today. Educators have organized various chapters at stand-alone charter schools throughout the city, and the union continues to advocate for progressive and just education policy. However, it has a fraction of its prior members and very limited power within the district. UTNO has also lost several high profile campaigns for collective bargaining over the last decade, which I think demonstrates, again, that a dearth of collective bargaining agreements doesn’t mean that teachers aren’t out here struggling and organizing.