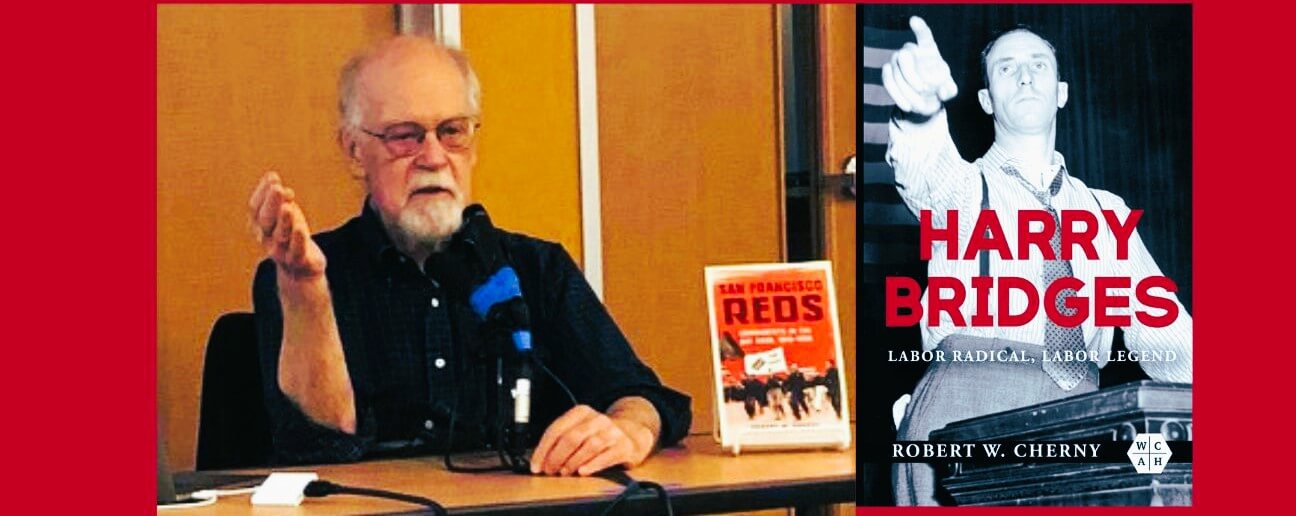

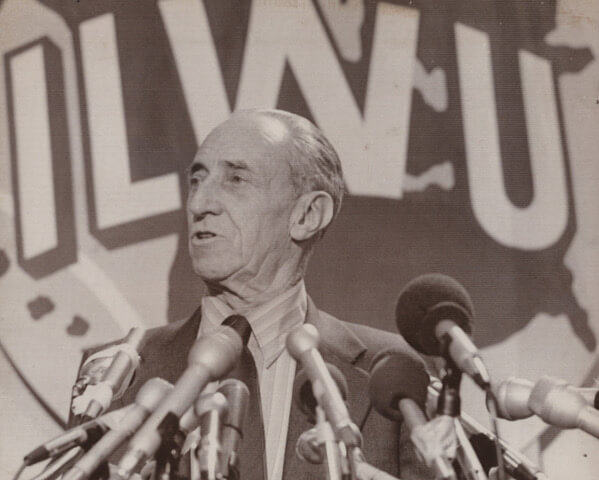

HS: It is an honor to be asked by Professor Rosemary Feurer of LaborOnline to interview Robert W. Cherny about his monumental 2023 biography of Harry Bridges. Dr. Cherny has written seven books in American history. He is emeritus professor of history at San Francisco State University. His Bridges biography has won three book prizes, including the John R. Lyman Book Award for Maritime Biography from the North American Society for Oceanic History; a Silver Medal in West Pacific Non-Fiction from Independent Publisher Book Awards; and an Honorable Mention for Book of the Year from the International Labor History Association.

Professor Cherny, your early books focused on mainstream Midwestern political history. How did you come to write a book about Harry Bridges, a West Coast labor leader often viewed as a radical?

RC: It started in 1985 with a telephone call from Nikki Bridges, Harry’s wife. Harry had retired in 1977. He had been charged by his union, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), to do his memoirs. Harry and Nikki worked on the project and then decided someone else should do the writing. I said to Nikki, “Sure, let’s talk about it.” My previous published work concentrated on the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, and especially on Middle Western politics and populism. But by 1985, I’d gotten involved with the Labor Studies Program at San Francisco State. I was on the faculty committee that developed the program. I’d already taught a labor history course. So Bridges wasn’t totally out of my previous range of interest.

I gave Nikki and Harry a copy of my biography of William Jennings Bryan. They looked through it, called me, and said, “Okay.” What they previously thought about was a ghost-written biography. But the historian Peter Carroll convinced them to do a proper academic job.

My agreement with Harry and Nikki was that I would be in control and we would do an academic biography, “warts and all.” Harry was onboard with that. They gave me tapes that had been done by Nikki and by another person they had contracted to do the ghost-written biography. I looked at the transcriptions and had a lot of questions for Harry myself.

What Harry often said in response to questions was, “It’s all in the public record.” It was. There was an enormous public record of Harry beginning in 1934 when he first hit the newspapers as chair of the strike committee for the San Francisco longshore local during the great ’34 West Coast maritime strike. Harry and Nikki gave me phone numbers of people to interview. I started that process. I started reading what had been written about Harry. One piece was your 1980 article surveying Bridges historiography. There was a 1972 biography by Charles Larrowe. He wrote a useful book, but it has its limits. There were archival collections that weren’t open to him then and other collections he didn’t use. He also relied heavily on just a couple of interviews. Still, it’s a useful book.

I did my secondary source research and made up a list of archival sources to look into. Fortunately, all this happened at the beginning of a sabbatical leave. I spent that sabbatical doing archival research all around the country. Over the next few years, including a couple of summers, I visited the National Archives, the Library of Congress Manuscripts Division, the Harvard Law Library, Special Collections at Columbia University, every presidential library from Herbert Hoover to Richard Nixon, and several ILWU locals along the Pacific Coast. I went to Hawaii to look at the ILWU Local 142 files.

In 1992, after Harry died and I could no longer ask him questions, John Haynes published an article about his research in Moscow at what is now the Russian State Archive of Social and Political History. The archive, then newly opened for researchers, has extraordinarily rich files of the American Communist Party collected by the Comintern. John said there he found documentation that in 1936 Harry had been a member of the Party’s US Central Committee. Fortunately, I got a Fulbright appointment for Moscow State University for Spring 1996. I spent a lot of time in the archive. I didn’t find much about Harry Bridges, but many interesting things about the Party in California I could use later.

Bridges was born in Australia, so that next summer I went to the University of Melbourne as a visiting researcher. I found records at state archives. I went to Canberra to look at the federal archives. At the university in Canberra I used the records of the Seamen’s Union of Australia. I went to Sydney to view the archives there. After the summer of 1997, I felt I had finished the archival research needed. I’d already drafted four or five chapters dealing with Harry’s early life. It was time to write more.

Communists in the Bay Area, 1919-1958 by Robert Cherny

But I got involved as chair of both my campus and the statewide academic senates and as dean of undergraduate studies. This took all of my time. Five years later, I had three books at various stages of completion, all derived from my initial research on Harry Bridges. One was a biography of Victor Arnautoff, a San Francisco artist born in Russia who eventually joined the Communist Party. The third book was about the Communist Party in San Francisco.

The University of Illinois Press was interested in all three books, so at that point I really dug in. The Arnautoff book came out in 2017, the Bridges book in 2023, and the San Francisco CP book in 2024. At first the Bridges draft was 900 pages. It was way too long for the press. I cut it by a third, mostly by consolidating the first three chapters into one.

HS: In addition to your research process, can you highlight your most important new findings?

RC: One of the things I discovered when I was in Australia was that some of Harry’s stories about his early life couldn’t have happened in the way he told various reporters later. I wrote an article about that. Still, this didn’t greatly change my thinking about the entirety of his life. More important, in 1985 I ordered Harry’s FBI file. It was enormous. It came in dibs and drabs until 2000. I learned a little about Harry, but a lot about the FBI and the Department of Justice in his various court cases charging him with being a Communist. The FBI files showed that the Department of Justice coached witnesses to the point of suborning perjury. One witness recalled, “They ‘refreshed’ my memory.” Another thing that’s clear in the Bridges FBI file is that the FBI burglarized his lawyer’s office in New York. The FBI called such acts “black bag jobs.”

HS: Getting on to Bridges himself, in the early chapters of the biography you note that he was the son of a real estate man in Melbourne. How did he become a seaman, a San Francisco waterfront worker, and a labor leader?

RC: Bridges’s father owned a lot of rental properties. He had Harry out collecting rent at a young age, including from some working-class families of his schoolmates. Harry found this embarrassing and distasteful. He had an alternative role model in his uncle, Harry Renton Bridges, a seasonal sheep shearer. Harry idolized him as a bushman who was at home in the outback but was also an advocate for the Australian Labor Party and a union organizer. Instead of calling himself Alfred, his name and his father’s, he began calling himself Harry. He read all of Jack London’s sea stories and hung out at the Melbourne docks. He wanted to go to sea. His father worked out a deal with the captain of a small ketch that sailed to Tasmania. Harry would be given the worst jobs to persuade him that this was not for him. But Harry loved it, stayed on, kept sailing to Tasmania, and became an able seaman.

When he was in New Zealand, Harry got a ship to San Francisco. He looked at the areas where Jack London had written. He shipped out from San Francisco and the Port of Los Angeles. On one trip he ended up in New Orleans. This was during the great 1921 seamen’s strike. He was recruited into the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which led him to rethink that era’s “Keep Australia White” convention.

The IWW lesson that class took priority regardless of race or sex became extremely important to Harry. He continued to advocate for that throughout his long career as a union activist. After the New Orleans strike, he came back to the West Coast and got a job in San Francisco on a coastal geodetic survey ship. In Oregon he met a young woman who joined him when he was back in San Francisco. Needing a job, he went to the waterfront and got on as a longshoreman. He always saw himself as a longshoreman thereafter.

It was a tough time to be a longshoreman on the San Francisco docks in the 1920s. There was no real union. There had been one that lost a strike in 1919. It was replaced by what was called the Blue Book Union because of the color of its dues book cover, but it was a racket. Men had to pay to the Blue Book to work, but there were no negotiations. There was a sweetheart contract. The Blue Book did nothing about working conditions; it simply collected dues.

HS: What about working conditions?

BC: The work was hard and dangerous. Longshoring in the 1920s was the second-most dangerous job in the country after mining. Falling objects were the source of most injuries and deaths. Harry was injured once when his foot was crushed. So there was a lot of built-up opposition to the Blue Book and anger among the men over working conditions. It was all casual labor, too. You were hired by the day in a “shape up” at the Ferry Building. Sometimes you had to pay a bribe to get hired. If you couldn’t find a work gang in the morning, you’d walk up and down the Embarcadero to see if somebody needed a fill-in.

HS: When the “Big Strike” came in May 1934, the West Coast maritime strike, it’s clear from what you’ve said why the workers wanted control over hiring. Another demand was for a coastwide contract. Why was that so important?

RC: What the union wanted was one contract for the entire coast so locals could not be played off against each other. The demand was for the same wages, the same working conditions, the same hours. That was crucial. The other crucial thing the men wanted was hiring by rotation through a union hiring hall. There would be no more shape-up.The work would be shared evenly among the men.

Bridges emerged into leadership when the new San Francisco International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) local held its first election. Bridges and some of his closest associates got elected to the executive board. When it was clear there was going to be a strike, the San Francisco local held an election for chair of the strike committee. Bridges was the only one nominated. San Francisco was the biggest port on the coast. It was also the headquarters of many shipping companies. Being chair of the strike committee put Bridge into the spotlight. There was a leadership vacuum in the local. That made the chair of the strike committee the de facto leader of the strike in San Francisco. Given the significance of San Francisco, Bridges exercised influence in the entire strike up and down the West Coast.

HS: The strike was quite violent along the coast. In San Francisco, two workers were killed by the police on Bloody Thursday, July 5,1934. That led to a San Francisco general strike in protest. There was a call for arbitration, which Bridges initially resisted. Why did he take that position?

RC: Theoretically, because in arbitration you lose control. You turn things over to someone else. You have no leverage. Bridges was also responding to practical experience. In the 1920s, so-called impartial wage boards arbitrated wage levels in the San Francisco construction industry. This had been a disaster for the unions and the workers. When President Franklin Roosevelt appointed a longshoremen’s arbitration board in 1934, one of the members of the board had served on the 1920s San Francisco boards. That gave Bridges concern about agreeing to arbitration. But finally the companies agreed to it. Fearing they would lose public support, the maritime unionists did, too. The longshoremen came out of it with almost everything they wanted. They didn’t get complete control of a union hiring hall, but the union would get to choose the job dispatcher. This ended the shape-up.

HS: A couple of years later Bridges decided, as I understand it, that arbitration could be beneficial to the union.

RC: Arbitration became an important element for what was an ILA district in 1934 and then, in 1937, became the ILWU. After the 1934 strike, there was a series of quickie strikes. What evolved was a unique system of arbitration where there would be port arbitrators by districts—Puget Sound, Columbia River, Northern California, and Southern California. Half were chosen by the union, half by the shipping companies. They were authorized to resolve disputes on the job site. If men at a pier said, “This job is unsafe; we’re not going to work,” the arbitrator shows up, looks, and says yes or no. There’s an appeal process to a coast arbitrator. That person’s word becomes law. This system of West Coast longshore arbitration, as nearly as I could discover, was unique in the world. It is still intact today in modified form.

HS: You note in the biography that Bridges was not technically a CP member. What kind of a relationship did he have with the Party?

RC: This was the central question during the whole time I was doing all that archival research. Bridges went through four hearings or trials between 1939 and 1955 in which his relationship to the CP was the central issue. In each instance, if he had lost, he could have been deported. He always said he had never been a member. I took him at his word, but I also did research in the files of the CP in Moscow and in all those FBI files. There is no evidence that he was ever a dues-paying member or was ever under Party discipline. In their big 1940 file, the FBI said, “We can’t find documentary evidence that he was ever a member.”

HS: Why did people go after him so much then?

RC: First it came from the shipping companies. It’s clear that companies and various patriotic organizations, especially the American Legion, attempted to prove that Bridges was a Communist. Eventually a CP membership card appeared. The FBI file makes it clear that the FBI knew it was a phony. Nonetheless, that card kept turning up. The House Un-American Activities Committee would bring it up. In 1940, a bill was introduced in Congress to deport Harry Bridges by name. It was unconstitutional and died in the Senate. Twice Bridges cases reached the Supreme Court. In the last trial, in 1955, the judge ruled in Bridges’s favor, essentially saying, “Good God, enough is enough. Leave this man alone.” That finally was the end of all the trials.

HS: There’s one more big topic, the 1960 Mechanization and Modernization Agreement (M&M), where Bridges accepted cargo containerization without a fight. This is still controversial. And, of course, AI is a major concern now. Peter Cole, in his 2018 book Dockworker Power, implies that Bridges gave up too much. Why, in your Bridges biography, do you conclude that M&M was an achievement?

RC: Bridges thought that you can’t fight the machine, you have to get a piece of it. That’s the way he put it. I have to agree you can’t fight technology. It’s going to happen. And in the longshore contracts going back to the 1930s, there is a provision saying something like, “We’re not going to object to labor-saving machinery as long as the workers are properly compensated.” Bridges himself always said, “Longshore work is backbreaking. We need to do whatever we can to keep people from being broken by the work.”

So did Bridges give up too much? Should he have not given up at all? Well, the ILWU set up a big operation to analyze how much the companies might save with this new technology. They shared the data. I interviewed one of the company people. He told me they were all flying blind in guessing how much the companies would save and how much they could share with the union. At one point, there was a company figure on offer. Bridges laid a longshore caucus figure on the table. The company representative said, “Where’d you get that number?” Bridges said, “Same goddamn place you got your number!” What they finally agreed to was that the union would not resist mechanization. In return, there would be a fund created to guarantee that every union member would continue to have a job or be paid even if there was insufficient work. It turned out that there were plenty of jobs for a while because of the war in Vietnam. Eventually, as the war ended and containerization advanced, it did reduce the size of the workforce.

So did Bridges settle for too little? I can’t say that he did. Should Bridges have asked for more? It’s twenty-twenty hindsight. Who could have anticipated what was going to come and how the technology was going to develop? If I have to come down on it, my argument would be that Bridges got the best he could get.

HS: in the second M&M, in 1966, Bridges agreed to let the employers hire steady men who would work for a particular company and didn’t have to go through the traditional hiring hall. Mostly these would be container crane drivers. Some people argue that this could split the loyalty of the workforce and weaken the union. Some also feel this led to the inconclusive 1971-72 West Coast longshore strike.

RC: Container cranes are huge, highly complicated pieces of technology. You can’t go from being a hold worker on a ship to operating a crane. You need training. Do the companies get special treatment in having people they train run their cranes? That’s the argument that led to the steady man. What the union finally agreed to was the argument that these steady men were in a separate category. And, yes, this became a major issue in the 1971 strike.

HS: Does that raise any kind of issue about Bridges’s legacy?

RC: I’ll tell you what I think Bridges’s legacy is. Bridges was committed to a couple of principles that remain embedded in the ILWU. One is that the union is colorblind. There can be no discrimination based on race, religion, politics, and ultimately gender. The relevant consideration is class unity. That part of the legacy has never changed. There were locals where Bridges wasn’t always successful in this, but he was always consistent in pushing to make it happen. The other part of his legacy is his commitment to the rank and file and to union democracy, which go together. He maintained contact with the rank and file. He’d travel up and down the coast to local meetings to defend the contract. Each longshore contract negotiation was preceded by a coast caucus for which each local elected delegates. Each local could send resolutions to be thrashed out regarding what was wanted in the next contract. Bridges supported that. This is a real exercise in union democracy. It is a level of union democracy that I think is unusual.

HS: Thank you very much for the interview.

RC: Sure. Happy to do it.

Author

-

Harvey Schwartz is curator of the ILWU Oral History Collection at the union’s library in San Francisco. His most recent book is Labor Under Siege with Ronald E. Magden. Other books include The March Inland: Origins of the ILWU Warehouse Division, 1934-1938 (1978; rpt. ILWU 2000); Solidarity Stories: An Oral History of the ILWU (2009); and Building the Golden Gate Bridge: A Workers’ Oral History (2015). He holds a Ph.D. in history from The University of California, Davis.