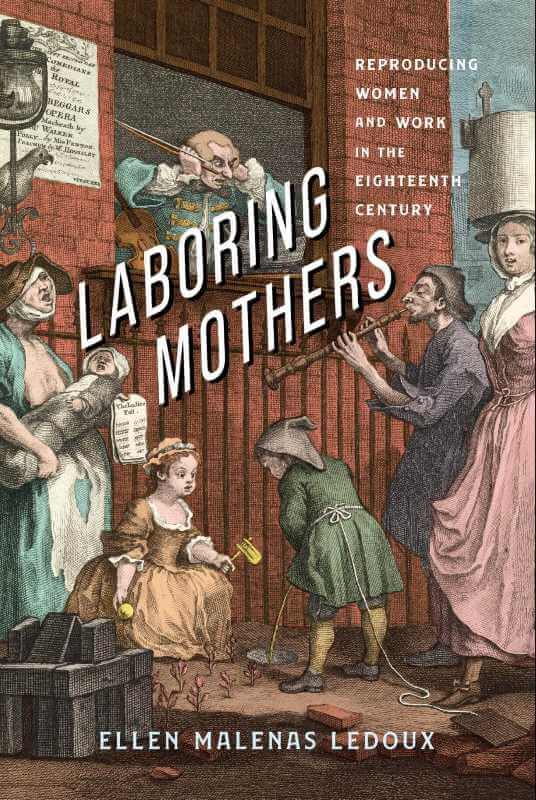

I am a scholar of the eighteenth century, specializing in cultural representations of women and their writing. While drafting my most recent book, Laboring Women: Reproducing Women and Work in the Eighteenth Century (University of Virginia Press, 2023), I was consistently struck by the parallels that exist between eighteenth-century mothers and the mother-workers of today, especially as they relate to so-called “work-life balance” and the intersecting axes of privilege and oppression that either create or foreclose this balance. Although a comprehensive reading of the last three hundred years of working motherhood is outside of this post’s scope, my book’s afterword discusses provocative examples of how twenty-first-century working mothers respond to the pressures of an idealized form of motherhood in ways that closely resemble the efforts of their eighteenth-century sisters. It also explores how society punishes a subset of these women (mainly the poor, uneducated, marginalized, or sexually stigmatized) who fail to live up to the unattainable ideal of the “supermom.”

While there is no neat one-to-one correspondence between eighteenth- and twenty-first-century women’s professional experience, there still exist striking similarities between celebrity mothers, midwives, soldiers, and women working in the sex trade. In describing their experiences, the afterword draws a through line between the Enlightenment overvaluation of the cult of motherhood[1] and today’s pressure for women to do and to have it all, encouraging readers to make connections that explain how our past representations of motherhood shape our current struggles in parenting.

I want to be clear about what I mean when I reference the “supermom” of today and the kind of intensive mothering she is expected to perform. She is the woman who is successful at managing both her career and her home, all while making it look easy and flawless. Part of the supermom’s credo is to engage in hypervigilance: making sure kids have healthy snacks, are wearing sunscreen, and engaging in activities outside of screen-time, and beyond. The perceived need for this type of intensive mothering tends to occur at the same time in the life cycle when women are also ramping up their careers, creating a veritable pressure cooker for women. In the discussion that follows, I want to offer some tantalizingly brief examples of how twenty-first-century women are coping with what I call “the cult of motherhood 2.0,” that is, an old set of unattainable maternal expectations that have their roots in Enlightenment constructs, simply expressed in new ways that reflect women’s expanded participation in the workforce.

“I want to offer some tantalizingly brief examples of how twenty-first-century women are coping with what I call “the cult of motherhood 2.0”

Privileged women continue to find ways to integrate their status as mothers into their professional persona in ways that bolster their career prospects. In the first chapter of my book, I trace how the most famous actress of the eighteenth century, Sarah Siddons, became adept at leveraging her children as a career asset by bringing them onstage at key life-changing moments. If we look at recent times, audiences still hunger to view celebrities performing motherhood as part of their professional life as entertainers. In 2019, then forty-nine-year-old pop icon Jennifer Lopez needed a public relations boost to launch her “It’s My Party” tour. Like Siddons, she harnessed the visual power of motherhood, including a duet with her then eleven-year-old daughter, Emme, in her new set. Audiences and critics swooned.[2] Instead of criticizing Lopez for exploiting a young child for personal gain, the media viewed the performance as endearing. As with Siddons, Lopez cannily found ways to not only integrate her motherhood into her work—thus removing the notion that work is a competing priority—but she also bolstered her professional profile by capitalizing on the public’s desire to see the celebrity as a caring mother.

This need to see female workers as caring mothers is especially acute in certain professions, most notably midwifery. As chapter 2 of my book discusses, female midwives framed their motherhood as a necessary credential for successfully treating pregnant women and newborns and to defend against the professional incursion of the so-called “man-midwife.” These arguments—that mothers make the best midwives—still influence women’s ideas about midwives’ qualifications today. In a 2015 article in The Guardian, midwife Gaynor Morrison recounts how, over a seventeen-year career, her childlessness was viewed as a negative by her clients. Studies of childless midwives support Morrison’s anecdotal reporting of feeling critiqued or judged by questions about the choice or necessity to remain childless. As Morrison points out, while patients will not think less of an oncologist who does not have cancer, pregnant women are skeptical of female midwives who do not know what childbirth feels like.[3] In this way, we see the legacy of eighteenth-century midwives’ contention that mothers make the best midwives as perhaps foreclosing professional opportunities for childless women and normalizing the enormous pressure to perform both domestic and vocational labor at a high standard in ways that are damaging to women today.

When a woman’s chosen profession is conceived of as anathema to the notion of motherhood—such as the female soldiers I describe in chapter 3—having children engenders vulnerability and derails professional advancement. Given this reality, it is not surprising that there are few mothers of young children in the current United States military. As The New York Times reports, “moms are still a rarity in the military. . . . insufficient childcare and unfriendly parenthood and pregnancy policies have been barriers to retention for female service members.” Thus, despite the extraordinary nature of the stories of female soldiers in the eighteenth century, the basic ways in which these women were asked to choose their military careers over their maternal obligations still remain in force today.

“Despite studies that demonstrate that with a minimum of support, prostituted women can thrive and separate their work from their valued parenting responsibilities, the notion that sex work precludes women from being competent mothers is yet another old idea that persists into our present moment.”

The mothers for whom the least has changed are those working in the sex trade. As it did in the eighteenth century, an uncomfortable silence surrounds the subject of prostituted mothers today. In my book’s final chapter, I outline the ways in which sexually stigmatized women were denied the cultural capital associated with the “cult of motherhood” by either having their status as mothers elided or being forced to relinquish their children to be deemed worthy of receiving charity. These Enlightenment constructs of maternity continue to be influential in today’s society, in which the idea of a prostitute being a “good” mother remains elusive. In our current moment, very few depictions of prostitutes as mothers exist, despite demographic data that suggests a large number of women work in the sex trade, many of whom are mothers.[4] As with eighteenth-century representations of prostituted mothers, twenty-first-century prostitute mothers’ motivation for engaging in sex work is largely economic and often related to a desire to provide for their children; however the way in which the provision is made carries a heavy stigma. As I detail in my afterword, this stigma finds expression in everything from societal disapproval to governmental intervention meant to remove children from a prostituted women’s care. Despite studies that demonstrate that with a minimum of support, prostituted women can thrive and separate their work from their valued parenting responsibilities, the notion that sex work precludes women from being competent mothers is yet another old idea that persists into our present moment. In this way, we see that some forms of stigmatized work performed by marginalized women creates insurmountable barriers to being perceived as the caring mothers that these women have the capacity to be.

“I hope to leave my reader with a sense of the great economic and cultural contributions women from all walks of life have made by documenting how women have always contributed meaningfully to industries, all while raising the next generation of people.”

While women’s lives have changed dramatically since the eighteenth century—women can vote, own property while married, and pursue advanced degrees—the ways in which prevailing ideologies about working motherhood continue to thrive on the promulgation of unattainable ideals remains largely the same. As my afterword details, these fantasies are not only marketed to women, they are also espoused by them. One professional woman, quoted in The New York Times, quips: “I shouldn’t be entertaining my baby when I’m working. . . . But I’m able to do it because I’m a mother—I’m superhuman.” This equating of maternity with superhumanity is meant as an empowering boast. Yet, as Laboring Mothers renders clear, the degree to which women can manage the so-called work-life balance largely depends on privilege based on class, race, sexual orientation, and gender identity, among other factors. At the same time, I hope to leave my reader with a sense of the great economic and cultural contributions women from all walks of life have made by documenting how women have always contributed meaningfully to industries, all while raising the next generation of people.

[1] Coined by scholar Felicity Nussbaum, “the cult of motherhood” refers to how middle-class English women were encouraged to limit themselves to a type of maternal domesticity seen as essential to nation and empire building. See Felicity Nussbaum, “ʻSavage’ Mothers: Narratives of Maternity in the Mid-Eighteenth Century,” Cultural Critique 20 (1991): 123-51.

[2] For a detailed account of the media and other celebrities’ reactions, see Ellen Malenas Ledoux, Laboring Mothers: Reproducing Women and Work in the Eighteenth Century (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2023), 223. For a more recent description of the destigmatization of pregnancy and motherhood in hip-hop, see Hillary Crosley Coker, “Female Rappers in the Spotlight Make Room for Motherhood,” New York Times, January 24, 2024.

[3] See Ledoux, Laboring Mothers, 224.

[4] For statistics on prostituted women as mothers, see Ledoux, Laboring Mothers, 226.

Author

-

Ellen Malenas Ledoux is an Associate Professor in the English and Communication Department at Rutgers University-Camden. Her research focuses on transatlantic literature of the eighteenth century. She is the author of two books: Laboring Mothers: Reproducing Women and Work in the Eighteenth Century (University of Virginia Press, 2023) and Social Reform in Gothic Writing: Fantastic Forms of Change, 1764-1834 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). She has published widely on women’s cultural history and Gothic writing in journals such as Studies in Romanticism, The Eighteenth Century: Theory and Interpretation, Women’s Writing, and Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture.