Chad Pearson’s review follows a series of recent posts from Labor Online that reflect on and feature the work of contributors to Contingent Faculty and the Remaking of Higher Education: A Labor History (2024) edited by Eric Fure-Slocum and Claire Goldstene.

This book is eye-opening. I found myself increasingly angry as I read these accounts of contingent laborers in today’s highly exploitative colleges and universities. It triggered me!!!!

The collection has many virtues. First, several contributors provide deep historical insights about the institutional and economic roles of colleges and universities. We learn about the university’s relationship with slavery, the long-standing ties between businesses and the academy, exclusionary admissions policies, and the overall elitism of many centers of higher education. Challenges to academic freedom, at least one contributor reminds us, are hardly new problems. And faculty organizing is not new. We must note the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) efforts since at least 1915 as well as its 1940 statement on academic freedom.

Yet, we must not fall into the trap of celebrating the idea that there was once a golden age, which some identify as the immediate post-World War II years. While we may see these years as more secure than today, the expansions of universities were tied to Cold War militarism that was provided federal funding; universities were critical players in the military-industrial complex. The social movements of the 1960s and 1970s produced necessary challenges to this mostly male and pale preserve, and today higher education is diverse in many areas.

Most, though not all, contributors believe that major economic and labor-related shifts in higher education occurred in the final decades of the twentieth century. Editor and contributor, Eric Fure-Slocum, starts the collection with an excellent historical overview of contingent faculty, noting the role that the “economic turmoil of the 1970s” played in producing a decades-long crises—that crisis continues to plague the academy today (3).

Most, though not all, contributors believe that major economic and labor-related shifts in higher education occurred in the final decades of the twentieth century. Editor and contributor, Eric Fure-Slocum, starts the collection with an excellent historical overview of contingent faculty, noting the role that the “economic turmoil of the 1970s” played in producing a decades-long crises—that crisis continues to plague the academy today (3). Others agree, including Joe Berry and Helena Worthen: “The higher education industry that contingent faculty work in today reflects the widespread application of neoliberal polices to education finance, governance, and workforce management” (58). Others remind us of the shrinkage of tenure and tenure track jobs and the expansion of contingent faculty and administrators. The average annual salary of contingent educators, $20,000, Fure-Slocum points out, falls “below the federal poverty guidelines for a three-person household” (4). These alarming trends are clear both in the US and, as Steven Parfitt explains in his essay, the UK. Though not noted in these pages, examples of academic inequality are present throughout Latin America and the European mainland as well.

Importantly, the growth of contingency and precarity was not inevitable. The explanation for the rise of a fundamentally unfair academy, expressed in the overwhelming number of talented contingent scholars with publications and excellent teaching evaluations, is, as Claire Goldstene explains, “as much political as it is economic” (268). Recent years illustrate increases in highly compensated administrators, which has coincided with the decline of tenured and tenured track faculty. And of course, the massive growth of educational workers without tenure, or the possibility of achieving it, does not mean that these people are any less committed to their profession. Despite confronting enormous financial and emotional challenges, many educators publish and demonstrate impressive teaching skills. Several contributors point out that the academy isn’t a meritocracy.

Some essays offer us personal glimpses into contingent educators’ many challenges: financial insecurity, reluctance to raise issues in the classroom that confront powerful people and institutions, and general feelings of what Goldstene calls “intellectual isolation” (270). I was especially taken aback by Diane Claire Raymond and Diane Angell’s chapters. Raymond served as a lecturer at the University of Virginia for thirteen years, and she never received a raise during this time. Furthermore, no one with the power to hire gave her the opportunity to move into a more comfortable tenure or tenure-track position, even though she is the author or editor of eighteen books! This seems like an extreme case, but I think many of us can point to examples of published authors laboring without the opportunity to achieve tenure. And Angell, a biologist, reports that she has routinely felt a sense of shame, even though her colleagues from various positions are generally polite. Yet, she notes, they “seldom serve as true allies” (125). These people have failed to, as Gwendolyn Alker puts it in her chapter, practice their “Marxist theory and advocate for those faculty who make” the jobs of researchers possible (80). And Angell raises an interesting and disturbing question about retirement after serving for many years as a non-tenured professor. She asks: “What does retirement look like when you will never be tenured”? (134). What legacy do non-tenured professors leave at these institutions?

According to Trevor Griffey: “The only time that non-senate faculty have made significant gains at the bargaining table with the University of California is when they have gone on strike or threatened to do so” (226). Others reinforce that central point.

Thankfully, the collection contains a good number of stories about resistance. I felt better reading the chapters in section three, “Challenging Precarity and Contingency in Higher Education.” Here we learn about effective graduate student and non-tenure track organizing. Anne Mcleer, an adjunct organizer in Washington, DC, explained this well: “By coming together collectively to unionize we had accessed the only means to successfully push back against institutional power” (205). And indeed, administrators have traditionally only budged when they felt that they had guns to their heads (not literally, of course). According to Trevor Griffey: “The only time that non-senate faculty have made significant gains at the bargaining table with the University of California is when they have gone on strike or threatened to do so” (226). Others reinforce that central point. Anne Wiegard tells us about her involvement in helping to form the New Faculty Majority while teaching at SUNY, Cortland. McLeer mentions the important financial benefits of union contracts and the necessity of building citywide solidarity in and around DC. The takeaway is clear: precarious educators in other communities should form their own central organizing committees designed to pressure college administrators to improve conditions.

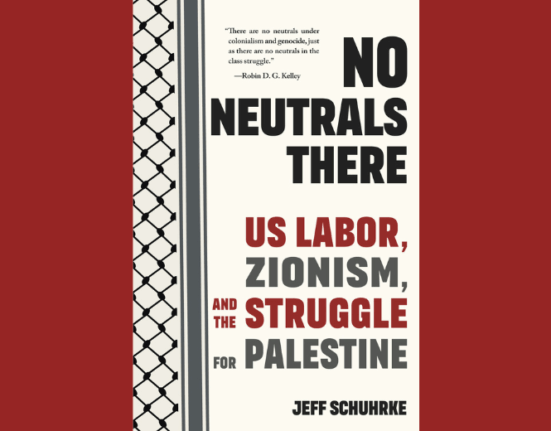

We can point to important organizing successes despite obstacles like the Supreme Court’s Janus V. AFSCME, which has created “right to work” policies for public sector employees. Griffey explains that the 2018 decision “seems to have helped more than hurt public sector labor unions, at least for higher education labor unions in California.” The decision has, as he puts it, forced union leaders to place a greater commitment to “internal organizing” and to “pay greater attention to the concerns of their members” (228). Naomi R. Williams and Jiyoon Park note that the decision has provoked a growing interest in promoting what they call “social justice unionism” (262). California is not the only place where member-driven organizing has led to strong unions and victories at the bargaining table. Jeff Schuhrke’s excellent chapter details the challenges and victories of graduate student employees. His experience in the 2019 University of Illinois, Chicago graduate student worker strike tells us about the hard work behind pulling it off. It was successful because rank-and-file graduate workers established solidarity with others, including professors, undergraduates, and community members outside of campus. Members of the union, the Graduate Employees Organization, he points out, “came away from the 2019 strike feeling empowered, learning that when graduate workers fight collectively for the respect and dignity they deserve, they can win” (201).

The power that graduate workers, adjuncts, and full-time non-tenure track employees show in the context of collective struggles has, of course, provoked cases of political pushback and administrator stubbornness. Their understanding of the power of collective action, McLeer points out, “explains why institutions spend so much money fighting unionization” (204-205). But many administrators, in consultation with union-busting attorneys, have been guilty of disseminating strategically unimaginative and highly predictable anti-union messages. It appears that the anti-union lawyers have become intellectually lazy, using the identical language that they have used in previous years. The recycled messages are often about how unions are inappropriate in academic settings and that they constitute an intrusive third party. Some suggest that administrators should have a chance to improve conditions without outside interference. McLeer reminds us that the targets of these statements are obviously critical thinkers. She notes, “that faculty contextualize and deconstruct texts for a living,” yet department chairs across one university used the “same language in their email” to all recipients (212).

Anti-union law firms are part of a larger consortium of right-wing organizations, thinktanks, policymakers, and politicians partially responsible for maintaining the problems of precarity and contingency. William A. Herbert and Joseph Van Der Naald insist that “Today, higher education is under fierce partisan, ideological, and anti-intellectual attack, fueled by the growth of a domestic fascist movement” (185). And as Goldstene puts it, “Those on the political right have long recognized the importance of the educational arena in their efforts to roll back the social and economic changes that resulted from the activism of the 1960s” (275). Goldstene spotlights the nefarious work of Lewis Powell, the future Supreme Court Justice who, working on behalf of the US Chamber of Commerce in 1971, expressed alarm at what he called the “Attack on the American Free Enterprise System” (274). Berry and Worthen highlight the ominous influence of the Trilateral Commission, a ruling class group that complained about student activism in the 1960s, which it labeled an “excess of democracy” (58). No doubt: forces on the right are responsible for the most high-profile attacks on higher education.

Yet right-wing individuals and institutions are not the only sources of our problems. At the more local level, plenty of provosts, deans, and department chairs, most of whom hardly view themselves as conservative, have stood in the way during graduate student and adjunct organizing.

Yet right-wing individuals and institutions are not the only sources of our problems. At the more local level, plenty of provosts, deans, and department chairs, most of whom hardly view themselves as conservative, have stood in the way during graduate student and adjunct organizing. Their anti-unionism probably has nothing to do with the influence of, say, right-wing organizations like the American Legislative Exchange Council. Instead, we must focus on their career ambitions, professional identities, and class interests. Indeed, these tenured professors and the administrators are more likely to see themselves as center-left figures—and many harbor some social justice consciousness. This is something identified by Raymond and Aimee Loiselle. Some were active in the Civil Rights movement in the late 1960s and Central American solidarity movements and the anti-apartheid struggles in the 1970s and 1980s. A few may have even been involved in TA/GA organizing when they were graduate students. Some have produced groundbreaking books about social justice issues and the evils of right-wing forces.

Consider cases from two rounds of organizing at Columbia University. Here graduate and teaching assistants faced-off against academic administrators who few would consider right-wing: Alan Brinkley in 2004 and Ira Katznelson in 2021. In a 2004 interview during the UAW organizing drive at Columbia, Brinkley, who claimed to be “a great supporter of unionization,” explained:

“All I can do is tell you the official University position, which is that the relationship between [professors] and teaching assistants is a complex, intellectual, educational, collegial, and also work-based relationship. And the position of the University, from the beginning of this issue three years ago, has been that the presence of a union mediating this relationship–the union in this case the UAW which has no previous experience, until NYU, within the academic world other than representing clerical workers–would somehow corrupt this relationship.”

Here Brinkley sounds like your typical annoying company man or Human Resource officer.

But the same offices where HR representatives seek to promote greater racial and gender equality are also the central planning spaces for union-avoidance activities.

In fact, we must explore the role of human resource offices in higher education and beyond. Human Resource employees can be both friends and foes. I think we can appreciate their involvement in promoting workplace diversity, and they have played useful roles in addressing cases of sexual harassment and bullying. But the same offices where HR representatives seek to promote greater racial and gender equality are also the central planning spaces for union-avoidance activities. These folks are involved in all stages of union-busting actions, and they almost always serve management’s interests. Thumbs up for their work in the areas of gender and race; thumbs down when it comes to labor relations! Bottom line: we must not focus exclusively on conservatives.

We must think hard about the question of adjuncts. Most fair-minded people across academic levels are uncomfortable about their low wages and precarious situation—if they are not uncomfortable, they should be! The way forward, contributors to this book have shown, is through organizing, including in states that are hostile to unions, including Florida and Texas. Having a genuine voice and contractual rights is critical. But let me be a bit provocative. I can classify at least two types of adjuncts:

1) Those who aspire to achieve more stable, generously compensated, and institutionally respected work.

2) Others, including retirees and, say, those who work full-time outside of the academy with no interest in full-time work in the academy.

Those interested in teaching a course or two are not the same as the highly ambitious scholars interested in full-time employment in colleges and universities. Consider, say, the labor lawyer who teaches a few classes in labor studies or law. This person might not be interested in leaving their law practice, but they probably do enjoy spending part-time teaching students about ways of collectively challenging the ruling class. How should we approach this group of people?

Of course, the interests of this set of academic workers are not the concern of the editors and contributors in this collection. But I think we can agree that a better system would provide pathways for talented and motivated adjuncts to move to more secure tenure track positions without penalizing those who have no interest in moving in that direction.

I want to conclude by thanking the editors and contributors for producing this excellent collection. I hope that it will inspire further discussions and, more importantly, needed improvements.

Author

-

Chad Pearson is professor at University of North Texas. His work includes Capital's Terrorists: Klansmen, Lawmen, and Employers in the Long Nineteenth Century (University of North Carolina Press, 2022) and Reform or Repression: Organizing America's Anti-Union Movement (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).