This essay by Justine Modica is available free until September 30, thanks to Duke University Press. Credit to Labor Online editorial member John Enyeart for facilitating this wrap around essay which previews the story in the essay. -editor

My “Worthy Wages” article, published in the May issue of Labor, grew out of the book that I’m writing on the history of child care as a labor issue in the United States. In the book, I explore the ways that various groups of Americans defined and contested the work of caring for children as it expanded in the late twentieth century as wage labor. The child care workforce, as I define it, includes workers who provide group-based care (workers in daycare centers and home-based family child care providers) as well as workers who provide private care for individual families (nannies, au pairs, and domestic workers).

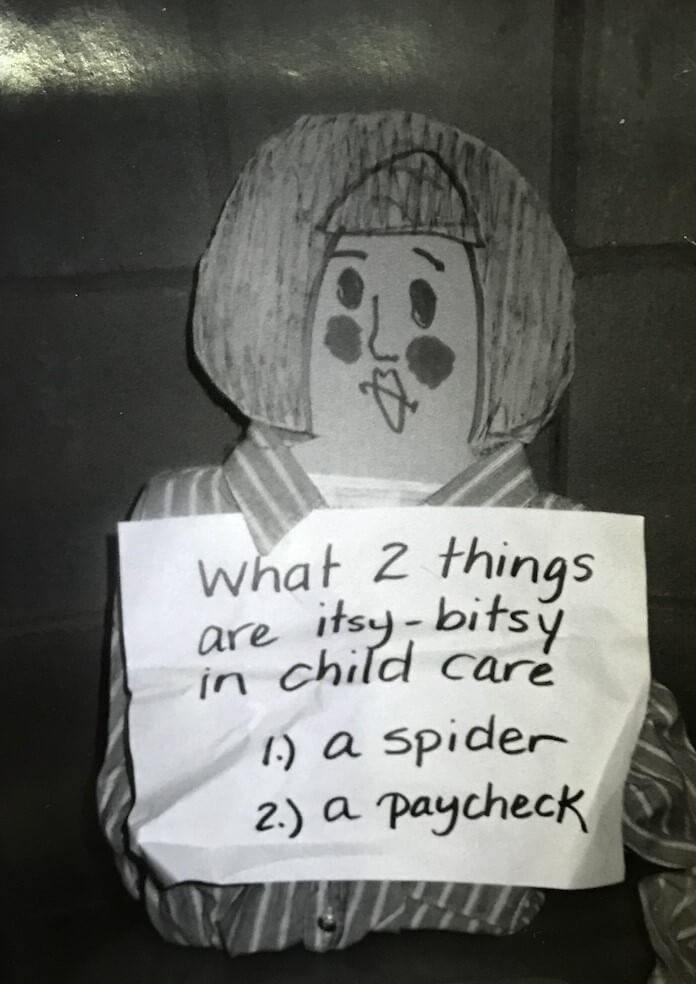

These workers are rarely considered as part of an aggregate labor force, yet their labor collectively underwrote the massive expansion of women’s workforce participation in the second half of the twentieth century. Few workers in the United States are paid as poorly as child care workers (who earn in the bottom two percent of all occupations nationwide), yet their labor makes all other work possible. My book examines the multiple factors that have historically suppressed the compensation of child care providers, despite their essential economic function and the high social value ostensibly placed on the work of caring for children.

In addition to looking at the downward pressures on the wages of child care workers, I also examine how child care workers resisted the social and economic undervaluation of their labor. Since the 1960s, child care workers and their allies have formed grassroots labor coalitions, unions, and advocacy groups to stress the importance of child care and to demand fair pay.

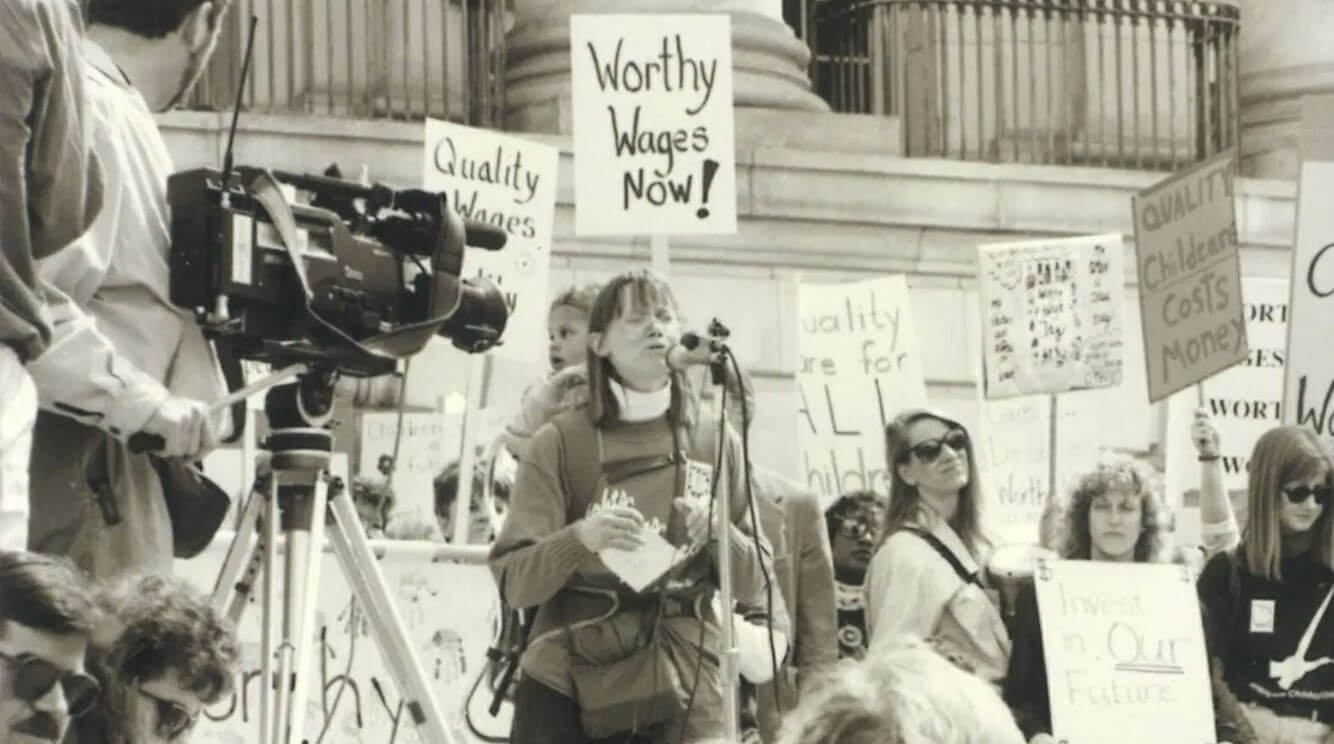

“Worthy Wages in the Emerald City” explores the national Worthy Wages movement in the context of Seattle. While Seattle launched the Worthy Wages movement, Worthy Wage chapters emerged in over thirty states. No city in the United States has ever succeeded in coordinating a citywide daycare strike, but Seattle’s activists were able to highlight the child care “subsidy” contained in their low wages by shutting down 75 centers for all or part of a day. Their aim was to briefly shift their burden onto families so that families might be inspired to lobby legislators for child care funding expansion.

To write this article, I interviewed twenty-two people who participated in child care activism in Seattle in the 1990s in some capacity, either as members of the Worthy Wage Task Force, as organizers with the Service Employees International Union, with whom the Worthy Wage Task Force affiliated, or as worker activists for culturally-relevant child care to meet the needs Black, Latinx, and Asian and Pacific Islander children. The conversations with a broad range of actors helped me to explore the landscape of child care activism in Seattle and how different groups of workers understood the most pressing issues in the field.

The Worthy Wage movement had limited success improving the material conditions of Seattle’s daycare workers. A daycare unionization campaign in partnership with SEIU collapsed when workers found limited room in unionized centers’ budget to improve wages without increasing parent fees. When SEIU turned its attention to family child care providers — home-based workers who cared for more children with state subsidies — they experienced more success. The large presence of state-subsidized children in family child care allowed the union to build an “employer of record” relationship with the state of Washington. This in turn allowed workers to bargain for better compensation without unduly burdening families, many of which could ill afford additional costs. In short, SEIU learned what Worthy Wage activists understood from the beginning: that any effective campaign to improve the wages of child care workers would need to shift the responsibility for child care costs off of private families and onto public coffers.