By William A. Herbert, Jacob Apkarian and Joseph van der Naald*

As this report documents, the recent uptick in union organizing has not been large enough to reverse the long-term decline in union density, yet the labor movement revitalization of the post-pandemic period is nevertheless an important development. Media attention has focused especially on the organizing drives at Amazon, Starbucks, Apple and other iconic brands. Yet while workers have voted to unionize in those companies, management intransigence has thus far meant that no collective bargaining agreements have been reached at any of them. By contrast, in other sectors of the economy, such as higher education and among medical interns and residents, the recent spate of organizing has led to significant gains.

Higher education is the industry in which such gains have occurred on the largest scale to date. Organizing among college and university faculty, graduate assistants and other student workers is not new, but it has accelerated in recent years, especially since the Great Recession. Equally significant, in 2022-2023, strikes have increased in higher education – in some cases among long-unionized workers and in others for union recognition. This special feature analyzes these developments in historical context.

U.S. labor unions have represented academic employees for more than half a century, primarily at public four-year higher education institutions and community colleges. (1) Over the past decade, however, successful unionization in higher education has accelerated sharply, especially among contingent faculty and graduate student-workers at private colleges and universities. Since January 2022, an even more dramatic upsurge took shape, primarily among student workers (both graduate assistants and undergraduates). This recent growth in student unionization has far exceeded that among faculty–whether contingent or tenure-track.

In the same period (January 2022 through mid-2023), faculty and student workers alike (as well as postdoctoral scholars and other academic researchers), have engaged in an unprecedented level of strike activity across the country, alongside the national strike wave taking place in other sectors. Although the largest stoppages in this period were at the University of California, notable strikes also took place in the New York area, at Rutgers University, the New School, and Fordham University.

Higher Education Union Growth, 2022-2023

The labor organizing upsurge among student workers has included teaching and research assistants in both the humanities and the previously quiescent STEM fields, as well as undergraduate resident advisors, student dining hall workers, and library staff. This new wave of campus labor activism, although larger in scale than before, builds on more than five decades of growth in higher education unionism.(2)

While graduate and undergraduate student unions are of long standing,(3) the increased scope and success of recent campaigns reflect several new elements. Those include: the recent rise in public support for organized labor with 77 percent of young adults approving of unions;(4) the increased centrality of social justice issues in student-worker organizing; the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on campus working conditions and its broader effect on public awareness of labor issues;(5) growing support for workers in higher education from industrial unions like the United Automobile Workers (UAW), the United Electrical Workers (UE), and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU); and the resourcefulness of undergraduate student-workers at Columbia University, Grinnell College, and Bennington College, all of whom successfully organized independent unions.

Alongside recent organizing at Starbucks, REI, Apple, and Trader Joe’s, the upsurge in student worker unionization reflects a wider labor awakening among younger workers. Union organizing has been trending upward among college-educated young workers, and especially those who are difficult to replace, like academic workers. For them, voting to unionize is far more likely to lead to recognition and a contract than among high-turnover and low-wage workers at companies like Starbucks, which has not yet signed a single contract despite hundreds of elections in which workers voted to unionize and repeated rulings by the National Labor Relations Board against the company’s anti-union conduct. The growing presence of higher education workers in established unions is far from trivial: indeed, academic workers now make up approximately one-quarter of the UAW’s membership.(6)

Figure B1 shows the rapid growth in unionization among graduate and undergraduate student workers for the period from January 1, 2013 to June 30, 2023. The line graph in this Figure shows the cumulative number of bargaining units, while the bar graph shows the number of new bargaining units added in each year — displaying the dramatic uptick that began in 2022. Indeed, during 2022 and 2023 alone unions won 30 new student-worker collective bargaining units, representing a total of 35,655 workers. Most of these involved graduate student workers, who comprise 62percent (19) of the new units – including two that also include undergraduate workers. Graduate students make up 93percent (33,314) of the total number of student-workers newly organized in this period.

The election margins in favor of unionization among student workers in 2022-2023 reflect broad support for labor. On average, 91percent of eligible student-workers voted in favor of unionization in representation elections in 2022-2023 (four additional units were recognized following card checks). These voting margins considerably surpass the 75 percent average of pro-union votes by graduate assistants in elections during the 2013-2019 period. (7) The 2022-2023 successes include union drives at Yale University, the University of Chicago, the University of Minnesota, and Johns Hopkins University, all of which had attempted but failed at organizing in the past.

Support from established unions for student-worker organizing has been instrumental in most of these victories, as Figure B2 shows. Since January 2022, the UE supported 37percent (7) of the new graduate assistant units, representing around 19,000 workers, whereas before 2022 the UE had represented only two graduate assistant units (at the University of Iowa and the University of New Mexico). The UAW, which has been a dominant player in student-worker organizing for decades, was certified to represent 21percent (4) of the new graduate student bargaining units in 2022-2023—involving over 5,600 workers. These two unions were followed by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), the Communications Workers of America (CWA) representing two new graduate student units, and the Office and Professional Employees International Union (OPEIU), the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), the Teamsters’ union, and UNITE HERE each representing one unit.

The growth in the number of undergraduate bargaining units is a notable new development. Prior to 2022, there was one long-existing unit of resident advisors and tutors at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, along with an undergraduate dining staff unit at Grinnell College. But in 2022-2023, new undergraduate student-worker unions were established at Columbia University, Barnard College, and Wesleyan University, among other campuses. Although these undergraduate units are noticeably smaller than their graduate assistant counterparts, this could change if the current SEIU campaign to organize 10,000 undergraduates at California State University is successful. (8)(8) These campaigns also involve different unions than those leading graduate student organizing. The OPEIU won recognition in 36percent (4) of the 11 new undergraduate units, alongside an equal number of recognized independent student-worker unions, as Figure B2 shows.

A comparison of 2022-2023 with the nine-year period prior to 2022 reveals the extraordinary and historic character of the recent phase of student labor organizing. The 30 new student bargaining units established since January 2022 represent a nearly 50percent increase over the total number of graduate and undergraduate student-worker units (21) organized over the entire 2013-2021 period.(9) Only three units were recognized during the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021.

In another departure from longer-term trends, nearly three-quarters of the new graduate assistant units and all the undergraduate bargaining units organized during 2022-2023 were at private colleges and universities. By contrast, prior to 2016, nearly all units were composed of graduate student employees at public institutions. Geographically, 70percent (21) of the new graduate and undergraduate student-worker bargaining units established since January 2022 were located in the Northeast, including 27percent (8) in Massachusetts and 23percent (7) in New York.

The sharp 2022-2023 uptick in student-worker union organizing overshadows activity among faculty, for whom unionization growth was slower than in the pre-pandemic period, as Figure B3 shows. (Like Figure B1, Figure B3 shows cumulative growth of bargaining units in its line graph, and units added each year in its bar graph.) Between 2013 and 2021, 126 faculty collective bargaining units won recognition, involving a total of 42,466 faculty. SEIU organized the largest share of faculty units over the period, 59percent (74), with a total of 25,963 (predominately non-tenure-track) faculty. In the 2013-2021 period, most of the new faculty bargaining units were at private (including both for- and non-profit) institutions, which accounted for 55percent (70) of the total. The bulk of newly organized faculty bargaining units in the 2013-2021 period were at institutions in Florida (16), New York (17) and California (18).

By contrast, only 11 new faculty units have been recognized since January 2022, involving less than 4,000 faculty members. Although growth was slower, it is notable that 10 of these new units (91percent) included non-tenure-track faculty. SEIU was the bargaining agent for 45percent (5) of these new units, which is consistent with its leading role in organizing non-tenure-track faculty over the past decade.(10) Although most new faculty units were at private colleges and universities, the two largest ones organized in 2022-2023 were at public institutions: Harrisburg Area Community College and Miami University, represented by the National Education Association (NEA) and the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) respectively. Six new faculty bargaining unions have won recognition in New York and California since 2022, two of them based at Skidmore College in upstate New York.

Whether the slower faculty unionization growth since January 2022 is a post-pandemic anomaly or symptomatic of a longer-term trend is unclear. Several new faculty organizing campaigns are currently underway, and they may well result in future growth, particularly among contingent faculty at private institutions. In addition, future growth at public institutions may occur as new legislation expands public-sector collective bargaining rights. The most recent example of this involves Maryland, where community college faculty were granted the right to unionize starting in September 2022.

Bargaining unit growth among post-doctoral scholars and academic researchers has been modest over the past the past year and a half. Prior to 2022, there were six post-doctoral bargaining units nationwide, and one unit of academic researchers, representing over 14,000 members in total.(11) Since January 2022, two new post-doctoral units and one academic researcher unit have won recognition, representing a total of over 2,000 employees.

Higher Education Strike Activity, 2022-2023

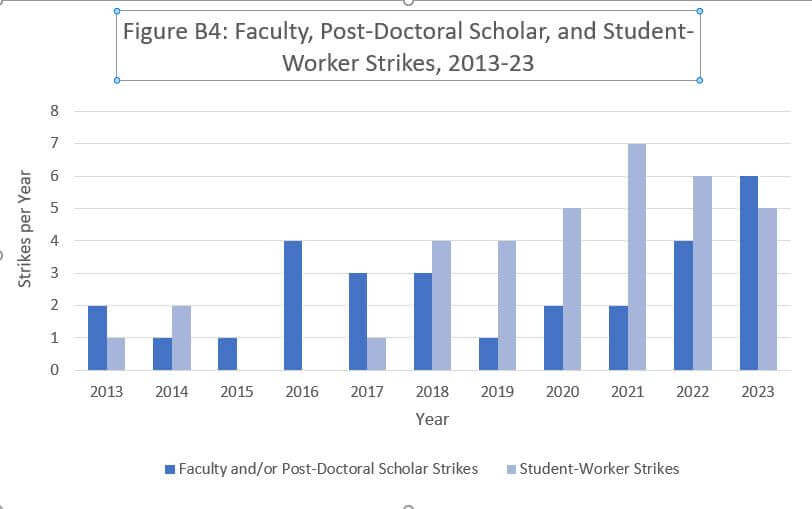

In addition to new organizing, in the period since January 2022 there were 20 strikes by workers in higher education, as Figure B4 shows. These strikes involved a mix of student workers, faculty, and post-doctoral workers. Almost a third (32percent) of all the strikes that occurred since 2013 took place in 2022 and the first half of 2023. Moreover, the frequency of strikes accelerated rapidly during that period, with fully half of the 2022-2023 stoppages taking place in the first six months of 2023. Six of the 10 strikes in 2023 involved faculty and post-doctoral units, and five involved student workers. (The strike at Rutgers University involved faculty, post-doctoral scholars, and graduate assistants and therefore appears twice in Figure B4, as does the strike at the University of California, which involved different bargaining units and ended on different dates.) Eight of the 22 strikes in 2022-2023 involved already-unionized graduate student workers, while three were undergraduate strikes seeking union recognition.

This explosive growth in strike activity in higher education is unprecedented within recent memory. In 2013-2017, there were only four student-worker strikes. The number began to rise in 2018, and growth continued thereafter, with at least five strikes in each year starting in 2019. While among graduate student-workers and faculty, national unions were the dominant force in these strikes, the pattern was different for strikes conducted solely by undergraduate student-workers, with seven of their 10 strikes since 2013 led by an independent union or conducted without a union.

College and university faculty strikes are not new. For example, there were 14 faculty strikes in 1977.(12) But such activity (and indeed, strikes in other sectors as well) had largely dissipated by the mid-1980s.(13) Faculty strikes increased slightly in 2016, with four strikes, followed by a slight decline until after the pandemic. There were four strikes by faculty and postdoctoral scholars in 2022 and another six in the first half of 2023, a substantial increase over previous years, as Figure B4 shows. Of the eight faculty strikes in 2022-2023, five involved combined units of tenured, tenure-track, and contingent faculty; two were limited to contingent faculty; and one involved only tenured and tenure-track faculty.

The strikes at the University of California in 2022 and at Rutgers University in 2023 exemplify a deliberate strategy of organizing simultaneous and coordinated work stoppages across separate bargaining units. The University of California strikes were the largest in the history of U.S. higher education, involving multiple bargaining units representing a total of over 45,000 graduate assistants, researchers, and post-doctoral scholars. The strike at Rutgers University was a wall-to-wall strike that involved over 9,000 tenured and tenure-track faculty, contingent faculty, post-doctoral scholars, and graduate assistants. The successful outcomes of those strikes may lay the groundwork for more multi-unit strikes in higher education in the years to come.

This special feature is guest-authored by CUNY’s National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions at Hunter College, which has collected data and analyzed trends in higher education union organizing, collective bargaining, and strikes since 1972. See William A. Herbert, “In the Beginning, Long Time Ago: A Brief History of the National Center’s Origin and Evolution,” Journal of Collective Bargaining in the Academy, Vol. 14 (2023) https://thekeep.eiu.edu/jcba/vol14/iss1/3/. The analysis is based on the Center’s collection of primary data, including certifications and decisions by the NLRB and public sector agencies, information posted on federal and state agency websites, responses from government agencies to freedom of information requests, news reports and decisions found on LexisNexis and Westlaw. The Center also thanks Bloomberg Law and the ILR Labor Action Tracker for enabling us to compare our strike data with their own as a means of verification.

1. William A. Herbert and Jacob Apkarian, “Everything Passes, Everything Changes: Unionization and Collective Bargaining in Higher Education,” Perspectives on Work, 21 (2017): 30-35. /wp-content/uploads/HerbertApkarian_POW_HigherEd_2017.pdf

2. William A. Herbert, Jacob Apkarian, and Joseph van der Naald, “Supplementary Directory of New Bargaining Agents and Contracts in Institutions of Higher Education, 2013-2019” (New York, NY: Hunter College, 2020). https://www.hunter.cuny.edu/ncscbhep/assets/files/SupplementalDirectory-2020-FINAL.pdf.

3. William A. Herbert and Joseph van der Naald. “Graduate Student Employee Unionization in the Second Gilded Age.” in Revaluing Work(ers): Toward a Democratic and Sustainable Future, ed. T. Schulze-Cleven and T. Vachon (Champaign, IL: Labor and Employment Relations Association, 2021), 221-46. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1739&context=hc_pubs

4. Meg Brenan, “Approval of Labor Unions at Highest Point Since 1965,” Gallup, September 2, 2021. https://news.gallup.com/poll/354455/approval-labor-unions-highest-point-1965.aspx

5. Rachel Berkowitz, “Physics graduate students join their peers in unionization efforts,” Physics Today, May 16, 2023. https://pubs.aip.org/physicstoday/online/42358/Physics-graduate-students-join-their-peers-in

6. Breana Noble and Jordyn Grzelewsk, “What the growing influence of higher education workers means for the UAW’s future,” Detroit News, April 23, 2023. http://rssfeeds.detroitnews.com/~/736972577/0/detroit/home~What-the-growing-influence-of-higher-education-workers-means-for-the-UAWs-future

7. Herbert and van der Naald, “Graduate Student Employee Unionization.”

8. Rocky Walker, “Cal State undergraduate workers seek union representation,” CalMatters, April 18, 2023. https://calmatters.org/education/higher-education/2023/04/cal-state-undergrad-unions/

9. Herbert and van der Naald, “Graduate Student Employee Unionization.”

10. Herbert, Apkarian, and van der Naald, “Supplementary Directory.”

11. Herbert, Apkarian, and van der Naald, “Supplementary Directory,” p. 20.

12. William A. Herbert and Jacob Apkarian. “You’ve Been with the Professors: An Examination of Higher Education Work Stoppage Data, Past and Present,” Employee Rights and Employment Policy Journal, 23 (2019): 249-77. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345387079_Youpercent27ve_Been_with_the_Professors_An_Examination_of_Higher_Education_Work_Stoppage_Data_Past_and_Present

13. Herbert and Apkarian. “You’ve Been with the Professors.”