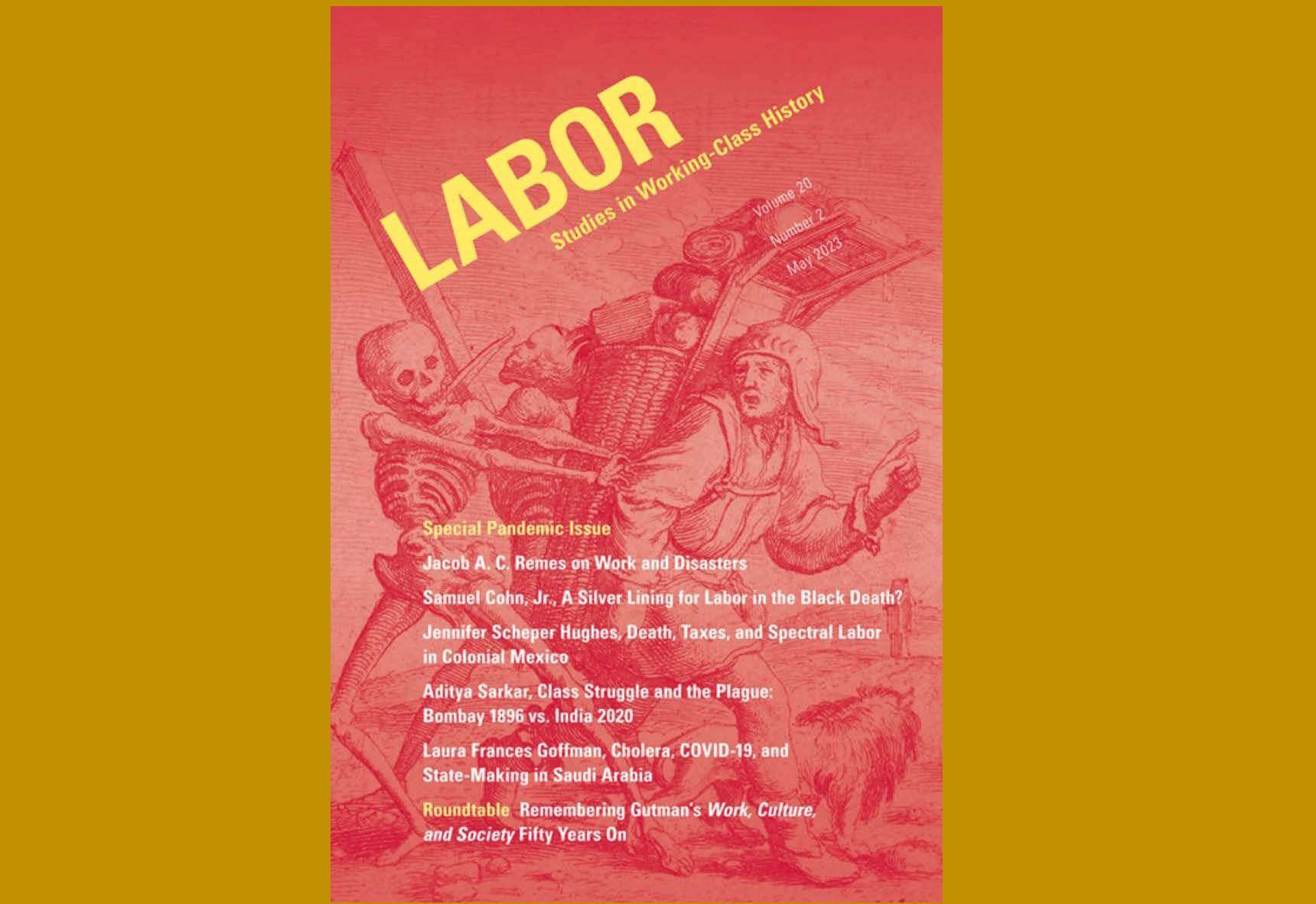

This is part of a series featuring authors of essays in the journal Labor: Studies in Working Class History. Jacob Remes frames the Covid pandemic to disaster studies, lending his perspective. The full essay appeared in the 20:2 (May 2023) issue of the journal. Subscriptions are part of LAWCHA membership.

Think back, if you will, to the early days of the Covid pandemic in March or April or May of 2020. It was in that period that LAWCHA members met by zoom and heard from Richard Trumka, then president of the AFL-CIO, a meeting that starts my brief historiographical essay in Volume 20, number 2 of Labor. You may have been afraid of disease and economic disruption. Many LAWCHA members were desperately trying to figure out how to teach in a new modality to traumatized and freshly evicted students – all while working on their living room couches after our bosses requisitioned our homes. Other workers, of course, were deemed “essential” and had to venture out into the world, putting themselves and their loved ones at increased risk of infection, disease, and death.

But you may also remember other things: an optimism that came from new political possibilities. To quote disaster sociologist Steve Matthewman: “National lockdowns showed that a supposedly unstoppable global economic system that should be privileged above all else – There is No Alternative – can be forced to a halt. Other ‘impossibilities’ were soon realised: homelessness was ended in Aotearoa New Zealand (albeit for a limited time during their first lockdown), free childcare was provided in Australia, hospitals were nationalised in Spain, basic income was granted in Canada, migrants and asylum seekers were given full citizenship in Portugal, and a number of countries trialled four-day working weeks.” In the United States, even in the midst of a grotesque politicization of public health, eviction and rent-increase moratoria, releases of some prisoners, a per-child payment to families, free health care (albeit only for a certain disease), and a student loan payment freeze – all things that seemed utopian a month earlier – were suddenly implemented, even if only in limited ways. Even defunding the police became a briefly mainstream proposition.

Of course from the perspective of July 2023, any optimism that we may have felt in spring or early summer of 2020 now seems misplaced. In mid-April 2020, a YouGov poll of British people found that large numbers saw improvements in their lives – a stronger sense of community, more social connections, better air quality, more wildlife – and that only 9% wanted to go back to the way things were before the pandemic. Over half hoped the their own lives and the country would learn from the pandemic and get better. Fast forward to today, and 63% of Britons say their country is heading in the wrong direction.

What happened? Why did the political possibilities that seem to blossom in the second quarter of 2020 fall off their stems and rot? Disaster scholars have long recognized “the increased intimacy and solidarity which characterizes populations in the post-disaster period,” as Kai Erikson described it in his classic Everything in its Path. Solidarity, with all the intentional political valence of that term, is a growing theme in disaster scholarship. But those of us who have written about it from a political perspective have too often waived away how short lived it can be. What disaster studies needs urgently now is to think about why the radical possibilities that were made visibly possible in the early pandemic did not last.

It is here, I propose, that labor and working-class historians can be especially useful. That’s not just because, as I write in my Labor essay, “almost every disaster is a workplace disaster,” or because disasters open up new terrains of struggle over political, employment, and family relations – although, as I write, those are two ways in which labor and working-class history intersects with disaster studies. In addition to these overlaps, labor historians are also especially well attuned to understanding failure and lost hope, how people have reconciled themselves to conditions getting worse, and to understanding why solidarity sometimes does not last or pay off. We study not only the cinematic successes of the labor movement, but also the suppression of it by forces of employers and reaction. Labor historians often have to wrestle with the question of why movements crumble, why it seems unions so often snatch defeat from the jaws of victory – and how seeming defeats can sometimes set the stage for future victories.

In my Labor essay, I presented ways in which labor historians have written about disaster, and how we can learn from disaster studies. But if disaster scholars are to learn from the dashed hopes of the early pandemic, we will need to gain insights from labor historians who do not explicitly write about disaster.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.