Beginning with this essay, we initiate a series on essays that are appearing in the journal Labor. This one is the backstory to how Francis Ryan, an expert on public sector labor, came to write his new essay in issue 19:2: “You’ll Never Walk Alone”: School Crossing Guard Associations and Labor Feminism in the Postwar United States . A subscription to the journal where you can access this article is part of LAWCHA. membership.

Like many children who started grade school in the 1970s, I walked to school. I attended a large parish school in Philadelphia six blocks from my home, and the stroll was not a direct line: to get there, I crossed seven streets and turned corners that led me to the yard where almost 1,500 children from first to eighth grades congregated before the opening bell. These streets I walked to were busy urban intersections—including the twelve-lane Roosevelt Boulevard—the busiest and most dangerous thoroughfare in the city.

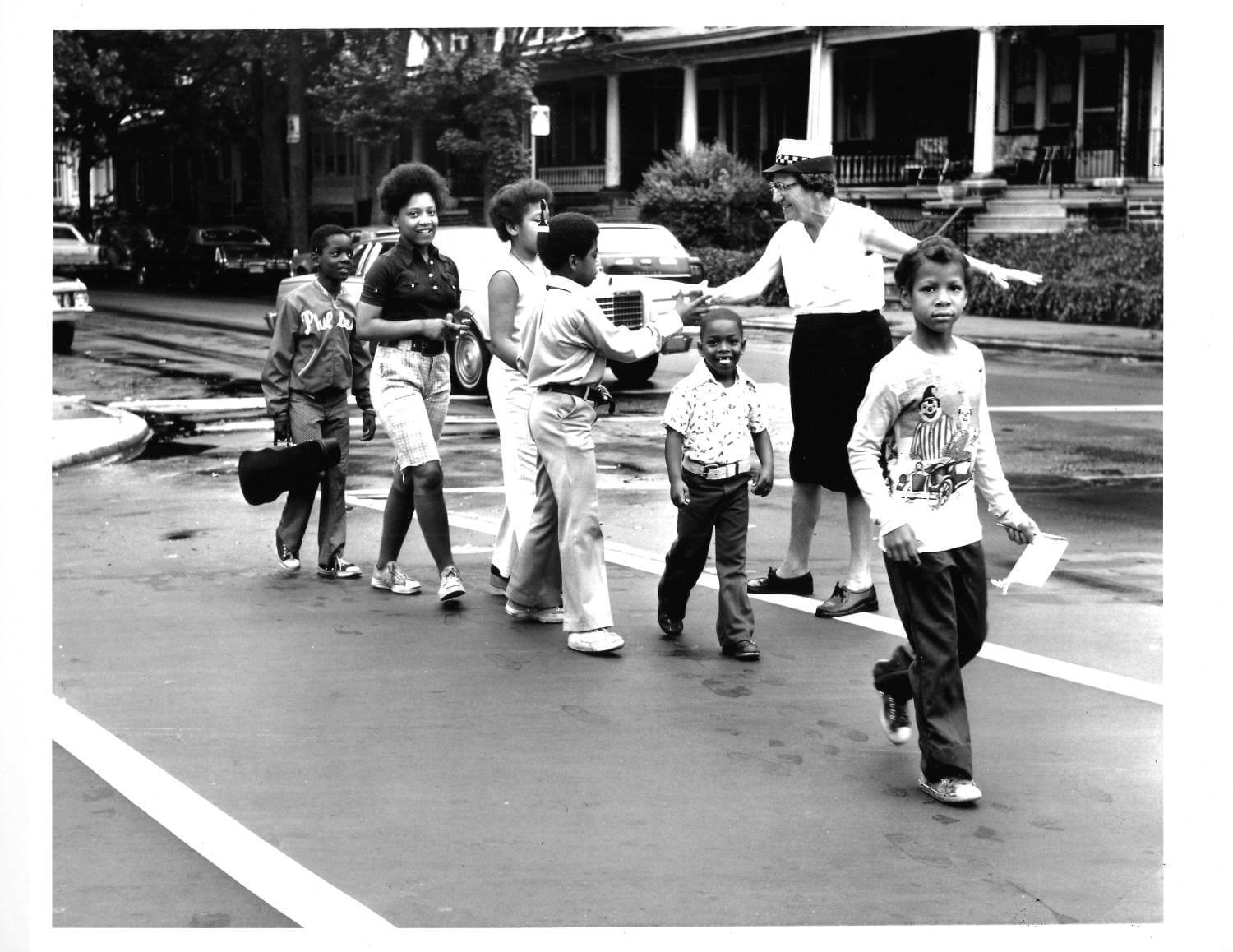

I began these daily journeys when I was only six years old. In these years many cars were as big as yachts, and I am sure that, as little as I was, it was hard to see me when I stood in directly in front of a car. Looking back, my parents were not as concerned as they might have been. I went to such a big school, and hundreds of kids were walking down these streets at the same time. With many older cousins and siblings in the mix, there was always some oversight. Even more than that, there was a sense of reassurance because at every busy intersection, there was a woman crossing guard assigned to help us pass safely. These women were a constant presence through these years. They remembered us, listened to our jokes, made sure we had our coats zippered, and more importantly, were vigilant in protecting us on these avenues. Even more than forty years later, I still remember them, even though I never knew their names. Some of them stayed on the assignment for all of the eight years I attended St. Martin of Tours elementary school.

Here’s a fact: in the eight years I attended this school, not one child suffered a serious injury while crossing the street. Not one fatality. This is an amazing figure when you consider just how many students clogged these neighborhood streets at morning rush hour, at lunch dismissal, and then again at 3 pm. I have no doubt that this is due to the work of crossing guards.

Fast forward a little more than a decade and I rediscovered the work of the school crossing guards. When I was researching the dissertation that became my first book, AFSCME’s Philadelphia Story: Municipal Workers and Urban Power in the Twentieth Century (Temple University, 2011), I began oral histories with some of the retirees of Philadelphia’s AFSCME council. I was surprised to find out that the city’s crossing guards were members of the council, as Local 1956. I had the opportunity to meet with and interview a good number of retired crossing guards. I especially remember my talks with Mrs. Catherine Nugent, one of the city’s original “patrol mothers,” whose stories of her work and her friendship with hundreds of fellow guards across the region inspired me to write a fuller account of these essential workers.

As I probed more, I moved beyond Philadelphia and noted a national story—and came to see how women crossing guards were among the most conspicuous advocates of a working class, labor feminism in the postwar era. My article in Labor: Studies in Working Class History 19:1 outlines this history across half a century–and seeks to place these women and the organizations they formed into the public eye.

So many of us have memories of crossing guards from our own school days, and I hope to hear from readers about their own stories of these public workers. I believe that this new history will help us understand how much the guards have done, and that we will appreciate their labor even more.

I thank all of those women who saw me safely across the streets many years ago, and for all who are out there now protecting our children. And I especially thank crossing guards Catherine Nugent, my old neighbor Mary Howells, and Philadelphia Crossing Guard Union leaders Bette MacDonald and Joan Gallagher for their encouragement and insights as I completed this article over the years.

Ed: Here is the precis for the essay:

In the years immediately following World War II, cities and townships across the United States implemented public safety programs to oversee road crossing for children outside schools. The crossing guards assigned to coordinate safe passage at busy intersections were primarily women and, as part‐time workers, were a distinct sector of an expanding public sector workforce. This article highlights the origins of these public safety initiatives and how crossing guards formed associations in the 1950s and 1960s to secure economic improvements. These independent organizations articulated an important variant of labor feminism in the early postwar era, and attention to the agendas put forward by these women opens new insight into this aspect of working‐class activism. Into the 1970s, many guard associations merged with AFL‐CIO unions, especially the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), becoming a catalyst for a range of programs that prioritized the needs of working women in collective bargaining agreements. The article concludes with an overview of the issues crossing guards and their organizations face in an age of increasing austerity in the new century.