I first met Jane LaTour over forty years ago on a picket line in the northern New Jersey town of Hillside.

Jane was working as an organizer for District 65, and I was coordinating the J. P. Stevens boycott in New Jersey for the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union. Walking the picket line on that cold, rainy morning created an immediate bond, leading to a warm friendship rooted in a set of shared beliefs, values, and sensibilities.

Although our geographic trajectories diverged, with Jane becoming ensconced in New York City and me traversing the northeast before settling in the Pacific Northwest, we remained in frequent contact over the years. Reviewing the “archival record” of our correspondence provides ample evidence of the qualities that made Jane such an influential figure and a valued and loyal friend.

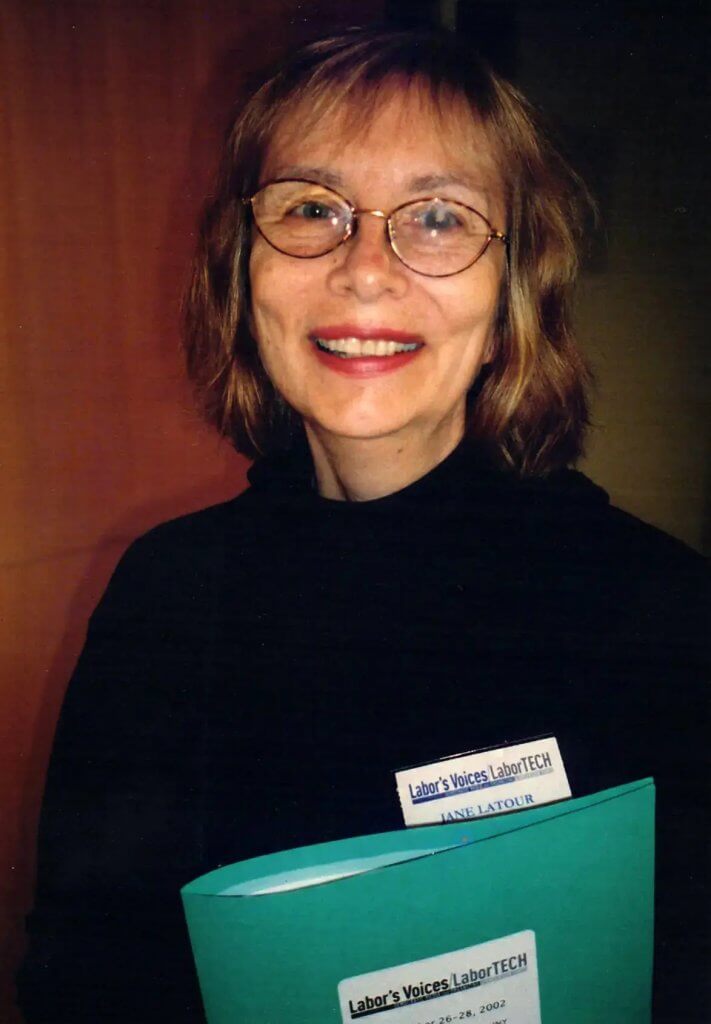

Jane’s profound commitments to the working class and the union movement were reflected in her multiple professional identities: journalist; historian; archivist; educator; organizer. She chose important institutional settings–the Association for Union Democracy, the Wagner Archives at New York University, AFSCME District Council 37’s newspaper, the New York Labor History Association–as venues where she could pursue her passions and practice her principles. Immersing herself in New York’s rich history and culture, Jane sought to honor the city’s diverse working class by making sense of its experience and becoming a vital resource for others who shared a similar mission.

Oral history became the perfect vehicle for some of Jane’s best work. An astute and empathetic interviewer, she helped workers tell their stories, recount their struggles and successes, and gain recognition for their achievements. Her indispensable collection of oral histories, Sisters in the Brotherhoods, told the stories of women entering traditionally male occupations and “making a way out of no way” as they “organized for equality in New York City.” Sisters ranks among our finest labor oral history publications, one that will set the standard for generations to come.

Jane’s deep affection for the union movement led her to speak truth to power throughout her career, repeatedly calling attention to instances where labor fell short of fulfilling its ideals. For Jane, the barometer of the union movement’s legitimacy rested in its willingness to welcome all workers, to amplify their voices, and to create opportunities for democratic engagement. Her final book, which will regrettably appear posthumously, uses oral history to report on the struggle for democracy within New York City’s unions. In an email she sent me several months ago, Jane wryly described the book as her “Pandemic Polemic” and eloquently explained her purpose: “I anticipate lots of blowback for this book, but my feeling is that we need to examine the topic in order to get the labor movement we need and not the one we have… the long history of sweeping it all under the rug is not the answer. So, onward.” Vintage Jane: candid; direct; visionary; and hopeful.

Jane’s unflinching honesty and integrity coexisted with a gentle wit, a generous spirit, and a deep sense of humility. She was one of the most gracious people I have ever known, expressing encouragement, appreciation, and solidarity as we shared stories about our personal and public lives. In every email she sent and in each of our personal encounters over the past few decades, Jane displayed these qualities, reminding me, as she put it in inscribing my copy of Sisters in the Brotherhoods, why our four-decades long friendship remained “one that endures.”

While perusing a shelf in my university’s library a few years ago, I made an unexpected discovery; Sisters in the Brotherhoods was standing directly next to my book, Fighting for Total Person Unionism. I am so pleased that my friend Jane and I will always be “next-door neighbors,” a fate that seems less like coincidence and more like destiny.