Editor’s Note: We select a featured essay from each issue of Labor: Studies in Working Class History. We’ve never featured a film review, and so it’s great to make available Richard Wells’ essay, Class Politics and the Filmmakers’s Craft in Mike Leigh’s Peterloo from issue 19:3 on the film Peterloo, released in 2018. It’s free until January 7, 2023. And below, Wells added to the essay with suggestions on how it might be used in educational settings.

When historians encounter films that cover times, places, and themes that are in their wheelhouse of expertise, the temptation is to rate the film based on what it did or didn’t get right. But films, and especially narrative films about well-researched historical events, just can’t cover all the ground that good works of history cover. As I noted in “Class Politics and the Filmmaker’s Craft in Mike Leigh’s Peterloo,” even non-mainstream filmmakers like Leigh can’t afford to get lost in the empirical richness of the historical record. They must draw from it, surely, but they must also make choices to create a story that, in some way, sparks the interest of the viewer. It means crafting a narrative that respects the work that historians have done, but also speaks to contemporary political, economic, and/or cultural themes. Peterloo (2018) does it well.

With this in mind, how might Peterloo work in a labor history class or labor education setting? Surely there are many angles to pursue. Here are just a few suggestions.

Building off the analysis of “Class Politics and the Filmmaker’s Craft in Mike Leigh’s Peterloo,” one could use the film as a point of departure for analysis of the complexities and challenges involved in a long-haul struggle for a more Democratic political economy. There are several thematic currents that run through film, for example, that are relevant to such a struggle in other times and places, and certainly in the present day.

For example, the film pays close attention to the role of the state in monitoring, discouraging, and violently suppressing the popular mobilization for parliamentary reform in the years before the 1819 massacre. Then there is the wonderfully satirical portrayals of how elites, from the Prince Regent and the Home Secretary in London to the Magistrates of Manchester, labeled an increasingly organized and articulate movement for radical reform as nothing but a rabble, intent on wholesale and bloody destruction. This points to the critical importance of the representation, the meaning, of such movements in the wider political imagination, and how this, too, is the site of class struggle.

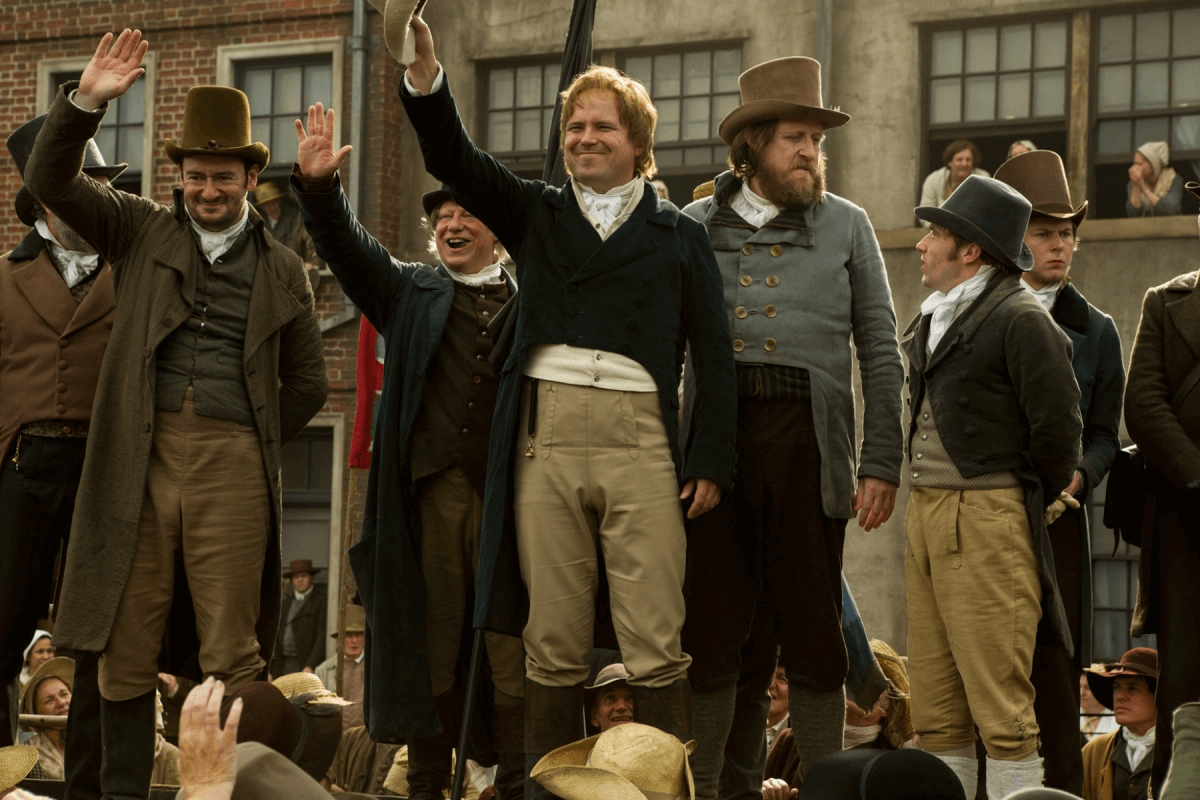

The film also raises important questions about how regional differentiation and class differences within can complicate both the organization and the leadership of working class social and political movements. A striking example of this in the film comes toward its climax, as gentleman farmer Henry “the orator” Hunt dismisses the Middleton based reform leader and silk weaver Samuel Bamford from the hustings. As Bamford leaves in a huff, a viewer might think that he was just fed up with Hunt’s arrogance, which may well have been true. But of equal importance here was that earlier in the film, Hunt refused to listen to Bamford when the latter warned of the violent tendencies of the local authorities. Things were different in Manchester, Bamford had advised. But Hunt was too enamored of his own rhetorical powers. In his hands, all would be well. They weren’t.

As pointed out by the New York Times film critic, A.O. Scott, the play of language in the movement of history is demonstrated, often extravagantly, in Leigh’s film. More specifically, the film explores the important role that mass demonstrations and oratory play in carrying forward a working-class movement. Just as importantly, the film sheds light on the limits of such tactics. Leigh and his actors capture how working-class audiences were drawn to the public language of reform, but also were uncertain about it–a skepticism born out of their own experience. Nellie, the matriarch of the working class family at the moral center of the film, perhaps captures this best. She, too, tried to warn of the violent proclivities of Manchester’s ruling class. And it was her son that soon lay dead on St. Peter’s Field. A still bigger question, then: was it worth it? And what does it take, in the end, to accomplish meaningful political-economic change in the face of all this?

Some critics were frustrated by the film’s inattention to the fact that early 19th century Lancashire was at the center of globalized system of violent expropriation and exploitation. Such may true, but Peterloo is none the worse for it. Still, a showing of the film could be quite useful in the context of courses or workshops that explore the history of capitalism. Peter Linebaugh noted that cotton makes a few cameos in the film, in shots of alleyways outside of the mills. Workers are also seen operating machines, pouring out of mills, struggling for existence, attending reform meetings. With the help of a reading and/or a careful synopsis of Sven Beckert’s Empire of Cotton, the emerging industrial capitalism of Lancashire can be connected to the “War Capitalism” that, in pursuit of a ready supply of raw of cotton, de-industrialized India and transformed its countryside, accelerated the growth of chattel slavery the Americas, and brought revolution to Saint-Domingue. Good discussion of how these global processes, and the more localized political and social movements that emerge in relation to them, might easily follow on.

Here are links to a few of the reviews cited in the published essay on Peterloo:

Scott, A.O. “’Peterloo’ Review: Political Violence of the Past Mirrors the Present,” New York Times, April 4, 2019.

Hornaday, Anne. “Mike Leigh’s Powers of Observation and Storytelling Fail Him in ‘Peterloo.’ The Washington Post, April 10, 2019.

Jones, Eileen, “Peterloo” is a Hard Movie to Like,” Jacobin, April 22, 2109.

Linebaugh, Peter. “Peterloo,” Counterpunch, May 8, 2019.