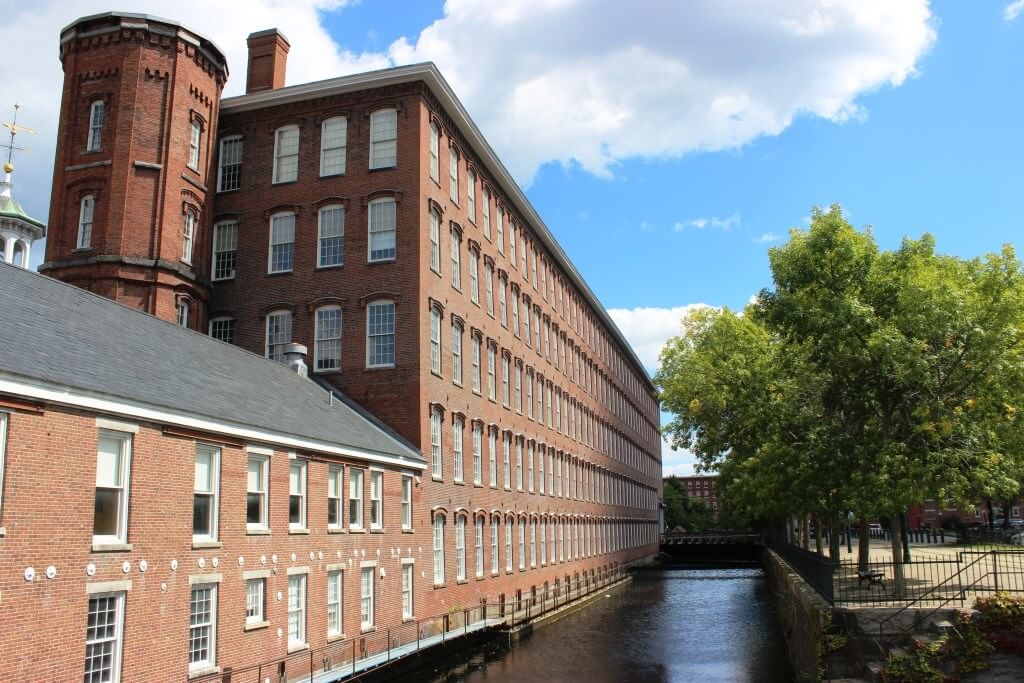

Lowell National Historical Park (LOWE) was founded in 1978 by the National Park Service. A sprawling site that includes the historic downtown of commercial Lowell, the canal systems, and the old mill buildings and boarding houses, the park allows visitors to trackthe evolution of industrial America in the 1800s. LOWE holds a unique place in the network of national parks as it encompasses not just one or two buildings but an entire neighborhood that is still a thriving business district as well as an eco-system of canals that weave throughout the downtown. The park plays a critical role in telling the history of early US industrialization through a variety of historical lenses such as the creation of mill towns, the changing demographics of the industrial workforce, environmental history including the transition from agricultural landscape to industrial landscape, the racist reality of United States capitalism through the interconnectedness of the early nation’s economic success and dependence on enslaved labor and low-wage work, and the changing cultural, social, and political fabric of a community as centuries of immigration shape the urban landscape. In short, a visit to LOWE has the potential to tell a very thorough history of the United States.

In an effort to ensure that their exhibits reflect an accurate historical narrative, the NPS partners with the Organization of American Historians (OAH) to hire scholars to research and write historical resource studies. Back in 2019, LOWE contracted with OAH to solicit a Historic Resource Study (HRS) in an effort to update their exhibit spaces at the Boott Cotton Mill and Boarding House. After submitting a grant proposal to the OAH, my colleague at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Stephanie Fortado and I were selected to conduct the resource study. Our task with LOWE was to write a new HRS that would consider the historical work conducted since the early 1980s when the first HRS was written for the Lowell complex.. This is no small task as we proposed to engage with many historical research streams beyond the most familiar labor history of LOWE. Typically a multi-year project, our HRS has taken even more time as we began the project just as the pandemic hit the US. We completed our first week long archive trip to the Center for Lowell History in late February 2020 with several more trips planned to Cornell University to see the recently relocated American Textile History Museum papers and to the Special Collections at Harvard University’s Baker Library. Naturally, the trips to Cornell and Harvard were put on pause as archives around the world closed their doors. We spent the pandemic reading historical scholarship on the environment, capitalism, business, labor, gender, sexuality, immigration, colonial America, Atlantic slave trade, indigenous studies, and more.

In our proposal we highlighted two priorities. First, the new HRS would be driven by primary documents rather than a 200-page historiographic essay dependent on secondary sources like the previous study. And, second, we wanted to engage the primary sources digitally. When visitors arrive at LOWE their first stop is often the Visitor’s Center where they meet park rangers, view a small exhibit space, watch a documentary about the history of Lowell, and, naturally, shop for cutetrinkets and souveneirs. Upon leaving the center, visitors then walk several blocks to access the Boott Mill and Boardinghouse exhibits, head to the canal to take boat tour, and/or take a trolley tour. It struck us during our initial visit that there are many lost opportunities as visitors walked through historic Lowell and a digital app would be an excellent way to narrate the history of the space in an interactive way that would allow the sharing of not only stories but also primary documents. For example, when a visitor stops to read the Lowell Institution for Savings Bank historical marker at the corner of Shattuck and Middle Streets, they only see the marker where the building once stood. With the StoryMaps app, they will be able to not only read the marker but also click on the spot through their app to view images of the building, read primary documents, and listen to a narration of a Lowell mill worker telling their story of saving their wages. They might even encountera historian offering more historical context about what it meant for young women to earn money for the first time or the shift from an informal economy driven by agriculture to an economy driven by wages and consumption. The StoryMap allows multiple senses to be engaged – viewing photographs, hearing a story, and engaging with primary documents all on a street corner – and thus moves visitors beyond the experience of simply reading markers.

Figure 4 – Lowell Institution for Savings, 1829-1992, Center for Lowell History

Stephanie and I quickly realized that creating a digital app was not in our wheelhouse so we brought on another partner, Heidi Dodson, a historian who is skilled in digital humanities and has been working closely with the NPS to gain approval for the LOWE StoryMap project. From the beginning, Heidi created a database template for us as we conducted archival research in which both Stephanie and I tracked all of the documents and images that we found in the archives with keywords, dates, sources, and notes on usability for the StoryMap. We maintain the database in a Google drive making it easily shareable among the three of us. As we build the StoryMap, we use this database to help construct the map. Our StoryMap is still in the draft stages, but the NPS has created a variety of StoryMaps to date that can be viewed here to give you a taste of the possible formats and approaches.

With a final launch date set for Summer 2023, this next phase allows us to think creatively about how our digital application will broaden out the narratives that the museum exhibits as well as the physical spaces throughout the national park.

We would love to hear from other public historians engaged in digital humanities in the comments below…

What are some best practices?

- What are pitfalls we can avoid?

- Have you used narration to bring primary documents to life?

- Is it possible to engage kids, young adults, and adults in the same StoryMap application?

- Other thoughts?

Cover Photo credit: Andrew Donovan, National Park Service, Lowell National Historic Park