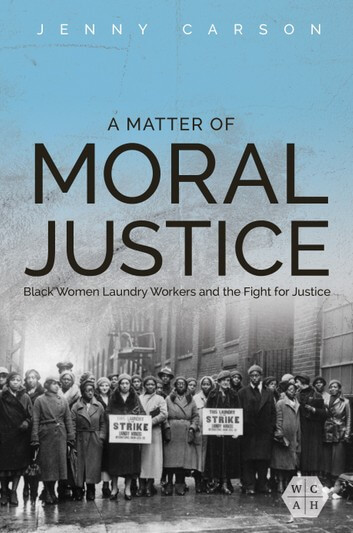

Jenny Carson profiles some of the dynamic early leaders of the New York laundry workers union uprising of the 1930s, and how their fight for a democratic union met resistance from a notable CIO union, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers. It is a window into her longer treatment in A Matter of Moral Justice, published by University of Illinois Press –editor

It was June 16, 1937, the twilight of the Great Depression, when more than one thousand laundry workers gathered in the auditorium at New York City’s Rand School of Social Science for what would later be remembered as the workers’ day of independence. Most of the participants, significant numbers of whom were Black, came from the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, where they had recently led a fourteen-week strike against substandard working conditions and sweatshop wages.

One of the leaders of that strike was Trinidadian transplant and long-time laundry activist Charlotte Adelmond. A militant Garveyite who was known for using “head butts” to slam abusive bosses to the ground, all without ever lifting a finger, Adelmond had been trying to organize her co-workers since 1933, using her own home as a campaign base. The Trinidadian organizer represented the inside workers, the mostly women and people of color who worked inside the plants washing, folding, drying and ironing clothes and linen. Adelmond was joined that summer by her good friend and fellow laundry activist Dollie Lowther Robinson. Robinson had migrated from North Carolina to Brooklyn with her mother in 1930 as a young teenager. Like so many other Black female migrants, she began her wage-earning career in a power laundry (by 1930 the power laundry employed more Black women than any other industry in the United States).

As organizers, Adelmond and Robinson worked alongside Louis Simon, Financial Secretary of Teamsters’ Local 810, the union that represented the white men who drove the city’s laundry trucks, as well as laundry worker and socialist Noah C. Walter of the Harlem-based Negro Labor Committee. Representing different constituencies and ideological commitments, the worker leaders were united by their recent activism on the picket lines and by their determination to halt the downward spiral in wages and working conditions that accompanied the Depression. Most significantly, they enjoyed the support of rank-and-file workers radicalized by fourteen hour work days, by racist and sexist treatment and by poverty wages.

Facing Down “Fear, Force and Poverty!”: The Laundry Workers Join the CIO and ACWA

The employers were not the only target of the laundry workers’ ire that summer. Adelmond, Robinson and their co-workers denounced the American Federation of Labor for its tepid trade unionism and reliance on a craft union model that divided the workers along occupational and by extension, race and gender lines. Fresh from a wave of strikes that had shut down some of the city’s largest laundries and inspired by the promises of the newly-organized Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO), the laundry workers voted unanimously to leave the AFL and join the CIO. Adelmond donated some of her own money to pay for the local industrial union charter issued by the CIO in June of 1937.

When the large employers’ associations that represented the different branches of the industry refused to negotiate with what they described as the new and “irresponsible” union, the established men’s garment union and founding member of the CIO, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA), offered to bring the laundry workers under its jurisdiction. The workers voted in favor of affiliation and in the summer of 1937 the ACWA-affiliated Laundry Workers Joint Board of Greater New York was born (LWJB). Within a year the nascent laundry union represented almost all of New York’s 30,000 laundry workers and had won contracts that included higher wages, overtime pay, paid vacations, a closed shop and the establishment of impartial arbitration machinery to resolve grievances, a victory that had eluded the workers and their allies for decades.

Black, Feminist and Radical Organizing in New York City’s Laundries

A Matter of Moral Justice: Black Women Laundry Workers and the Fight for Justice (University of Illinois Press, 2021) tells the story of how the mostly women and people of color in New York’s laundries formed their union during the Great Depression. It also chronicles the less triumphant story about what happened to that union under the CIO and ACWA in the post-war era. The book challenges the dominant narrative that attributes the union’s founding to the intervention of high-ranking CIO and ACWA national union officials, including ACWA President Sidney Hillman, and more accurately locates the union’s origins in the decades’ long struggle waged by the workers and their allies to form a union.

Since the 1910s, New York’s women laundry workers enjoyed the support of a diverse group of allies, including members of the cross-class and feminist labor organization: the New York Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). Under the leadership of socialist cap maker Rose Schneiderman, the WTUL emerged as an early and consistent supporter of New York’s women laundry workers, using race and gender-conscious organizing strategies that included collaborating with suffragists, Black churches and Black social reform organizations. WTUL leaders harnessed the prestige and resources of the League’s upper-class “allies” to shine a spotlight on the laundry’s abysmal conditions and on the specific exploitation of women workers of color. Ensconced in fur coats, in 1934, at the height of laundry worker organizing, elite League members Cornelia Bryce Pinchot, wife of Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot, and Grace Childs, wife of prominent businessman and anti-union Republican Richard S. Childs of Childs’ Restaurants joined the mostly African American women on the picket lines in Brooklyn striking for higher wages and respect on the job. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt lent her Secret Service agents to the strikers who came to the picket lines armed with sticks and rocks to defend themselves from the thugs hired by the employers. Rose Schneiderman even convinced Republican Mayor Fiorello La Guardia to turn off the water in two large Brooklyn laundries where workers were on strike.

Even earlier, in 1931, radical laundry workers and organizers from the Harlem section of the Communist Party, including Jessie Taft Smith and Beatrice Shapiro Lumpkin spearheaded the formation of the short-lived left-led Laundry Workers Industrial Union. In a prelude to the industrial and interracial unionism of the CIO, the radicals united the mostly women and people of color inside the plants with the more highly-paid white male drivers. Communist organizers and Black workers made the pursuit of racial justice central to the campaign, calling for the eradication of the discriminatory hiring practices and wage scales that saw Black women confined to the lowest-paying and most difficult jobs in the ironing department.

New York, 1936, Credit: Daily Worker.

Interracial activist solidarities were forged through militant acts of unionism that included putting stink bombs under the doors of strike breakers, piling into the police vans when one of the leaders was arrested (Dollie Robinson described those who were arrested as “aristocrats of the movement”) and, in Taft Smith’s case, chaining herself to a mezzanine pillar of the Taft Hotel (chosen for their shared name) when the owners refused to stop sending their linen to the Sutton Superior Laundry where workers were on strike.

Black socialists and trade unionists from the Negro Labor Committee, community and left-led organizations including the Women’s and Unemployed Councils, and local housewives provided food, funds and organizing and moral support for the workers whose activism drew inspiration from the broader culture of protest animating Harlem and other Black working-class communities during the Great Depression. Under the leadership of shop-floor militants like Adelmond and Smith and aided by a diverse set of allies who came together in an early demonstration of Popular Front unity (1935-1939), in the early and mid-1930s the laundry workers forged the interracial activist solidarities that culminated in the formation of the ACWA-affiliated Laundry Workers Joint Board.

The Laundry Workers Joint Board and the “Democratic Initiative”

As worker leaders with huge rank-and-file followings, Adelmond and Robinson quickly won positions in the new union. Described by the workers as “outrageous and outspoken,” the much beloved Adelmond served from 1938 to 1950 as the sole Black female business agent in the union. Legendary for wearing a man tailored suit, a fedora and cutting her hair short in an Afro before it was popular to do so, workers celebrated Adelmond for the militant tactics she used (head butts!) to organize new shops and enforce the contracts. The Garveyite was equally respected for her uncompromising commitment to racial justice, a commitment that saw her just as likely to challenge a racist union boss as an abusive employer, often at great personal cost.

Robinson worked alongside Adelmond but deployed more diplomatic tactics that included building alliances with progressive white unionists such as ACWA Vice President Bessie Hillman, mentoring workers of color and, in 1943, taking on the position of Education Director of the union. As Education Director Robinson organized social, cultural and athletic activities for the workers and their children, as well as classes in trade unionism, programming that contributed to the broader goals of racial empowerment and union democracy.

Alongside eight other female Black laundry activists, in the 1940s a group Robinson dubbed the “Democratic Initiative,” pursued a civil rights agenda, demanding that the union challenge the racist and sexist hiring practices that persisted post-unionization, as well as the longstanding employer practice of paying women less than men, even when performing the same job (much to the women’s dismay, the union allowed for the inclusion of gender-based wage differentials in the collective agreements).

During WWII, the “Democratic Initiative” linked their activism to the broader goals of the “Double V” campaign to defeat fascism abroad and racism at home. When the ACWA launched a blood drive in 1941 for the troops abroad, Adelmond led the workers in a protest against the Red Cross’s racist policy of segregating the blood of Black and white donors. The “Democratic Initiative” demanded that the federal government make the Fair Employment Practices Committee permanent (the committee created by President Roosevelt in 1941 to enforce Executive Order 8802 banning discrimination in defense industries) and that the LWJB enact the principles of fair employment by negotiating a non-discrimination clause in the laundry contracts.

During and after the war the workers led and participated in marches against segregation and police violence and many, including Robinson, joined New York State’s left-wing American Labor Party through which they organized for civil rights and economic justice. Under Adelmond’s leadership, in 1948 the workers drafted a resolution demanding that Ethiopia be compensated by her former colonial aggressors, a reflection of the Garveyite’s pan-Africanism and of the increasingly international outlook of Black Americans who, in the 1940s, linked their struggles against white supremacy at home with the independence movements being waged by people of color abroad.

The laundry workers’ organizing took inspiration from and contributed to the dynamic civil rights unionism animating the post-war urban North, activism that historian Jacquelyn Dowd Hall describes as the “first decisive phase of the modern civil rights movement.” A decade before Rosa Parks sparked an uprising that toppled Jim Crow, Adelmond, Robinson and their co-workers were organizing for economic and racial justice, part of what scholars now recognize as the “long civil rights movement.”

Racism, Sexism and Business Unionism in the CIO

White male officials in the ACWA and LWJB were threatened by this rising activism that connected labor rights with civil rights. Beginning in 1938 with the first contracts, garment officials imposed an organizational structure and vision on the union that privileged labor peace and stable contractual relations over meaningful gains at the bargaining table or racial justice for Black workers. Under the ACWA, a familiar and dismal system of routinized collective bargaining and bureaucratic, legalistic business unionism took root in the laundry union.

When the “Democratic Initiative” and their radical allies challenged this unionism, top garment officials retaliated with suspensions and expulsions. In an early Cold War move that would culminate in 1949 and 1950 with the expulsion of some of the most dedicated anti-racist organizers from the labor movement, in 1941 the ACWA expelled the communist founders of the LWJB, including Jessie Smith and Beatrice Lumpkin.

For the first but not the last time, in 1940 the ACWA leadership suspended Adelmond for insubordination. The Business Agent had publicly accused an ACWA Vice President of racism for arbitrarily removing African Americans from elected positions and replacing them with white workers. The Black publication the New York Amsterdam News, which followed the laundry union closely in the 1940s, described ACWA leaders and their handpicked white male laundry officials, including former driver Louis Simon, as behaving like “colonial agents” towards the majority Black and Puerto Rican workers.

The conflicts that ensued between Black workers demanding economic and racial justice and their white male union leaders culminated in 1950 with the ousting of Charlotte Adelmond and the reassignment of Dollie Robinson to the South. Black workers, who decried the women’s removal, told the Amsterdam News that Adelmond had been kicked out for challenging the union’s “dictatorial rule, shady practices and Negro discrimination.” Adelmond believed that she had been ousted for her militant opposition to the “second-class treatment of Black workers” and refusal to play the part of “handkerchief head Negro.”

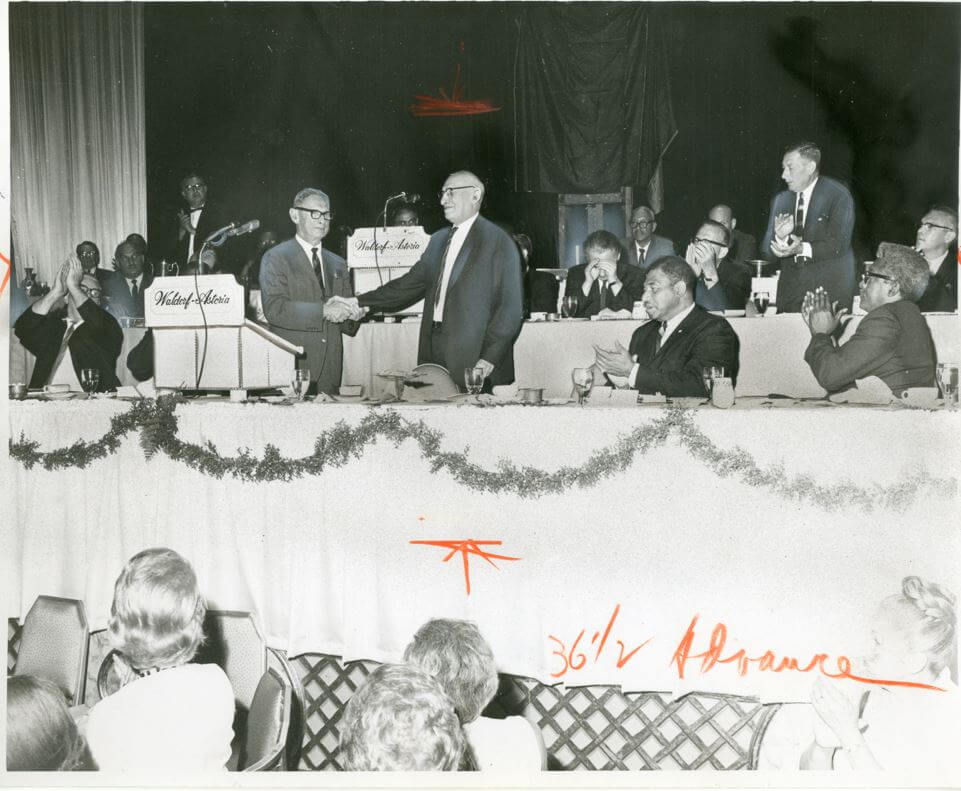

Shorn of its Black and radical founders, Louis Simon took over the position of head of the union in 1950, a position he held until 1982. Despite the rampant allegations of union corruption and racism leveled against Simon by Black workers, the erstwhile driver enjoyed an illustrious career as a civil rights hero, serving on the boards of the Urban League, the United Negro College Fund and on the National AFL- CIO Civil Rights Committee. Under his leadership the race and gender-based job assignments and wage scales remained intact and women and people of color continued to earn barely subsistence level wages.

Building a “Democratic Initiative” in the 21st Century

The story of the laundry workers then is a familiar one of racism, exploitation and missed opportunities. In 1966, after thirty years of no strikes in New York’s laundries, close to one-half of the union membership earned less than the $1.50/hr. minimum wage set to go into effect a few months later, and women and people of color continued to earn the lowest wages and perform the most difficult jobs inside the plants. The business unionism that flourished in the LWJB – and in some other unions formed under the CIO- and the suppression of the civil rights unionism of workers like Adelmond and Robinson sowed the seeds for at least some of organized labor’s challenges today, including worker distrust of unions.

If we want to understand why some workers have been reluctant to devote their lives to the project of union building, the history of New York’s laundry workers reveals that it was not lack of initiative, but rather the suppression of that initiative in the service of labor-management cooperation that provides some of the answers.

Yet the history of the laundry workers is also a story of hope, a story about how some of the most exploited workers came together during the Depression to build an interracial and industrial union that brought New York’s notoriously anti-union laundry employers to the bargaining table. The workers’ organizing and activism was rank-and-file lead, militant, intersectional, anti-racist and community-based. Workers forged solidarities by marching together on picket lines, by engaging in acts of civil disobedience, and by building a dense network of community and labor alliances that augmented their rank-and-file organizing.

Ejected from the laundry union, many of the women founders went on to have distinguished careers in the labor, civil rights and women’s movements. After decades of labor and civil rights work, in 1961 President Kennedy tapped Robinson to work in the Department of Labor. She, alongside other mid-twentieth century labor feminists, helped found the National Organization of Women.

Radical laundry organizer Beatrice Lumpkin, who began her social justice career organizing laundry workers in the 1930s, continues to organize today at the young age of 103. Among other activities, she helped found the Coalition of Labor Union Women, joined civil rights marches and has and continues to organize with the Steelworkers’ and Chicago Teachers’ Unions. The cards were stacked against the women founders of the union in the 1940s, but their struggle mattered and their stories help us to understand how workers might build a “Democratic Initiative” in the 21st century.