Mark Lause looks at the 1793 yellow fever pandemic in Philadelphia from a working class history perspective, and finds it informs us today.

As an unrepentant participant in the original Earth Day half a century ago, I have a well-honed intellectual awareness of the fragility of a modern, complex, globalized civilization, but I never thought I’d see it demonstrated at my doorstep so dramatically. Before Covid-19 reached my community, I had been bracing for it for some days. When it did, the ordinary operation of everything from restaurants to libraries to universities collapsed at the speed of gravity. In mid-March, officialdom acknowledged the implosion with orders to shelter in place, but I have daily ventured out, if only to give the dogs a short run. Beyond my home, the streets of what had been a vibrant American city, usually jammed with traffic, lie empty, and people pass each other self-consciously covering their mouth and nose with a mask or scarf, as do I.

All of this has recalled a book I encountered, as a graduate student decades ago. Arthur Mervyn; Or, Memoirs of the Year 1793 tells the fictional tale of a young manual laborer coming to Philadelphia to make a better life. Then the nation’s capital, it remained its largest city. As of the country’s first census a few years earlier, it had nearly 43,000 in the city with another 12,000 in adjacent communities, indicating that it had yet to recover from its experience of battle and occupation in the War for Independence, which had officially ended only a decade earlier.

The Outbreak of the Contagions

Most of the population still lived seven or eight blocks from the wharves and warehouses along the Delaware River. The streets remained generally busy and crowded, with commerce along High or Market Street and with labor as one neared the river. Like any such booming city, rents and necessities of life tended to be high, while wages remained rather modest. People lived in streets that would later be called alleys and crowded into rooms with as many people as they could stand cohabiting. The quality of water generally ranged from unsatisfactory to unspeakable and that of the food remained frequently uneven.

Philadelphia had just lost the most celebrated of its citizens, Benjamin Franklin, but cherished the aphorisms and attitudes he published, to his great personal profit, in Poor Richard’s Almanack. It promised a system in which honesty, sobriety, and industry would reap it’s just rewards, a rationalization for those with wealth and power and an implicit promise for those without to work harder. Implicitly sharing this sense, an Arthur Merwyn from the back country—or his peers from Britain, Ireland, Germany or France—could seek a better destiny for themselves alongside the richest and more remembered men of the age. After all, they had established a land of enlightened liberty that had recently legislated into existence a population of “Free Africans,” alongside a decreasing residual population of slaves.

Contemporary events elsewhere had already begun to overshadow the promises of 1776. In 1789—as the United States government began functioning—France experienced its revolution, the repercussions of which swept through its colonial holdings. On the island of Santo Domingo in the Caribbean, the slaveholders who paraded about with their new tricolor cockades wound up facing a revolution by their African and mixed race “inferiors,” who outnumbered the propertied whites by far more than ten to one. The successful revolution begun in August 1791 represented more than the war of an elite of local property holders for independence from a foreign power, but actually transformed the society.

The demographics of slavery there made it almost impossible for whites to have made a living entirely unconnected from slavery, and the revolution naturally assumed aspects of a race war. White refugees began turning up in ports ringing the north Atlantic. What they brought with them, besides a few unfortunate personal slaves, would transform the country.

Indeed, by 1793, the specters of Toussaint Louverture and his comrades had already begun to haunt the nightmares of slaveholders on the American mainland. It certainly became a factor in their fearful rationalizations of slavery which started to replace the older professions of slavery as an admitted evil that could not be disposed of easily. The morbid tendency to panic about slave revolts also coincided with the invention of the cotton gin, which made American slavery an integral, lucrative feature of the textile production central to a trans-Atlantic Industrial Revolution.

More immediately, though, the refugees from Santo Domingo brought swarms of hangers-on in the form of the humble mosquito that carried a virus with which the new U.S. was about to become lethally familiar. From August into November 1793, the epidemic devastated the showcase city of the United States. Its unexpectedness left the most educated doctors dazed and its thoroughness successfully evaded the development of a genuinely effective treatment. Many of those who could afford to do so left the heat and humidity of summer in those eighteenth century cities by heading off to their country estates.

With the advent of the disease, those who had opted to stay rethought their decision, packed up and headed out. With the yellow fever in town, some 20,000 others left, most having no country estates, but perhaps relatives or friends in the country with whom they could shelter, or who would provide space for them to camp. Until relatively recent times, the makeshift shelters of squatters ringed the large American cities, and some of the working poor, who were no longer going to be working, hiked out to join them, expecting to fish and forage for survival through the immediate future.

Into that real plague city strolled the fictional Arthur Merwyn. As we meander through our familiar yet unfamiliarly deserted streets, we might fancy ourselves following in his footsteps. However, we are not stepping over the corpses left in the walkways with families of mourners clustered about some of them. We do not see mass trench graves dug in our parks and city squares in an effort to get the diseased bodies underground as quickly as possible. However, in humility, we should remember that Merwyn would not have seen these things in the early stages of the plague that descended on his community.

The Symptoms

The virus slammed the victims with flu-like muscle pains, headaches, vomiting, with alternating fever and chills. After, a few days of this, the disease either relents or plunges as many as a quarter of the infected into a final, lethal stage. A hemorrhagic fever sets it, attacking the internal organs, and creating the hepatitis that causes the jaundice associated with a “yellow fever.” Doctors formulated treatments, argued over their effectiveness, and ultimately found themselves incapable of doing much more than making the victims as comfortable as possible through their final hours.

In the absence of those born to rule, management of city largely fell into the hands of those who were born to work and be poor. In the novel, Merwyn comes down with the fever himself. After barely surviving, he joins the effort to treat the afflicted. In reality, the most organized effort to care for the sick came from the local Free African Society. Several thousand black residents of the city participated in this new mutual aid organization led by the Methodist ministers Richard Allen and Absalom Jones. Methodism came out of the religious revivals earlier in the century, and became particularly attractive to African Americans, which did not always comfort the movers and shakers of the denomination. In response to this Allen, Jones and others began moving towards a more self-reliant Christianity.

The city fathers encouraged black interest in taking on this role, partly because of the mistaken notion that they would tend to be immune to yellow fever as they largely seemed to be to malaria. Events quickly proved this wrong, but the black community of Philadelphia plunged into the work of caring for as many victims of the epidemic as they could. It is no exaggeration to say that thousands of whites who survived owed their lives to a black attendant regularly braving the chance of infection with a glass of water, a touch, or a word.

One of the most truly eerie aspects of the epidemic they all faced was that they could not know how long it will last. Human civilization has done such a reliable job of parsing out lives into discrete chucks of time that we may otherwise forget that days, months, seasons, years are beyond our poor power of management. As with many of us, serious outbursts of bad weather have provided us some experience with enforced sheltering. We recall our impatience at the inconvenience of spending a day or so under an ice storm or a hurricane or a few hours because of a tornado.

Notwithstanding the orchestrated cheerleading and promises to reboot the economy by ignoring the coronavirus, it looks likely to keep our lives and movements on a short leash for some time to come.

We see bits of the old preoccupations even in the midst of the crisis. Before the end of 1793, Matthew Carey, the wealthy philanthropist published his A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, lately prevalent in Philadelphia. It uncritically repeated slanders common among whites who had not actually been in the city, stories that charged the blacks tending the sick with ineptness, brutality, and even stealing. So too, in our day, we have heard the government that failed to provide needed equipment to New York hospitals insist that the absence was not due to its gargantuan mismanagement but the sticky-fingered people risking everything to treat a disease.

Historical Memory & Social Amnesia

Like our predecessors, we seem to have noticed and started discussing changes in the world around us. The relative quiet and, for those of us that don’t’ have the TV running constantly, the rediscovery of solitude, for better as well as for worse.

People are noticing that the air is cleaner and the natural world, in the form of wildlife, is already grazing and foraging at the edges of humanity’s engineered version of the world. Most of us are finding it delightful.

Without the smog, most of us see the world we humans have made for ourselves more clearly, the injustice and unfairness of it coming into sharper focus. The most essential workers right now are those who provide society with the medical care and maintain order, to say nothing of the far more numerous the fast food provider, the retail grocery workers, the janitors and launders in the hospitals and public spaces. Folks who make measly fractions of what’s paid the corporate and government functionaries who usually get to define importance based on how much they pay themselves. Or the media stars who ever ratify those priorities.

Not surprisingly, people tell themselves that things will change, once we get through all this. We are allowed to console ourselves with such pious aspirations. That people on TV say such things reminds us that they, too, share our humanity. However, they clearly tend to draw the line where such insights discomfort the comfortable.

Those who lived through the 1793 epidemic thought they and their contemporaries would also remember the experience of responding as a community and emerge as better people with a better society. Charles Brockden Brown, that pioneer of American literature who penned Arthur Merwyn certainly wanted people to remember. The first American to make a serious attempt to earn a living by writing fiction, Brown also became the first—and not the last—to fail at it, which is why he turned to political journalism.

Yet, I’m sure Brown’s work there would have made as rough a fit at MSNBC as at Fox. He admired William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, both friends of that disreputable old unrepentant revolutionary Tom Paine. Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) informed Brown’s other writings on women’s rights, and he drew elsewhere on Godwin’s anti-institutional Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793), an unintimidated critique of hierarchy and privilege.

In the end, though, while those who lost someone will cherish memories of the individuals we may have lost, society tends to bury our large numbers of dead as quickly as possible. They are buried our collective memory as well as the graveyards. It’s not an accident that the first historical book on the 1793 epidemic did not appear until 1940, when J.H. Powell’s Bring Out Your Dead!

Much of this has to do with the cocoon modern capitalist society weaves about itself, the way it defines the world only in terms of its most self-interested, self-referencing standards. In my lifetime, I’ve seen us learn the costly bloody lessons of Vietnam and seen the dominant institutions of the society work hard to forget them before the war was even over. In short order, they shrunk the importance of Watergate and Iran-Contra to fit “inside the beltway,” neither perceived in their vital relation to developments in southeast Asia, Central America or the Mideast.

We know now that there were people out there ringing the alarm bells about the coronavirus—as there were for the 2008 implosion of the U.S. economy—but we somehow didn’t have time to discuss those forebodings. And when it does hit the fan, the people awarding Nobel prizes in economics pretend that nobody saw it coming and award their accolades to those who were telling us that everything was going to be fine.

What will most immediately inform how the people generally process this experience will depend on the industries of mass communication, the corporate entities that decide what’s important enough to merit serious coverage and what isn’t. That hierarchy of priorities erects and maintains a sense of “normalcy,” that non-word invented by one of our first modern media presidents, Warren G. Harding.

Certainly, those hopeful of learning from the past are not cheered when the individual to whom our society has spared no expense to make the most well-informed in the world publicly says that nobody saw the epidemic coming or had any idea it was going to be this bad.

Most discouraging, has been that, when the president says this, nobody in the room laughs. The lack of such an appropriate response informs us of what they wish to normalize . . . or the kind of normalcy to which they are so eager to return us.

The Impact

Of course, whatever our understanding of events at the time, they have their impact, and the change wrought by the 1793 epidemic were real enough. New people poured into the void it created and generated a greater dynamic that the city had earlier had. Seven years after the epidemic, Philadelphia’s population had topped 81,000. Nevertheless, it had already begun losing ground relative to New York City, which passed it by 1810, remaining the largest city in the country thereafter.

More immediately, Allen and Jones went on to organize a black response to their ostracism by white Christians, the African Methodist Episcopal Church. The AME quickly became a central institutional pillar of African American communities across the country. Along with Prince Hall masonry, it became a key fulcrum of antislavery activity up to and including an active role in assisting the escape of runaway slaves.

More subtly, the memory of black Americans acted to save the city likely contributed to the transition of antislavery sentiment in Philadelphia, from a Quakerish distaste into a more active resistance. Over the generation after the epidemic, Philadelphia became one of the critical centers of the Underground Railroad.

In the changing world build on the ruins of the epidemic Brown offered Alcuin, his dialogue on the rights of women. Like the best of his class, he believed in the values of the Enlightenment and the persuasive power of the written word. Brown cast his verbal confrontation between an unreflective gentleman with a genuinely independent women in the gentil parlor of his intended readership. Over the next generation, after those readers remained predictably unpersuaded, women such as Frances Wright took the issue of female equality over their heads to the people generally.

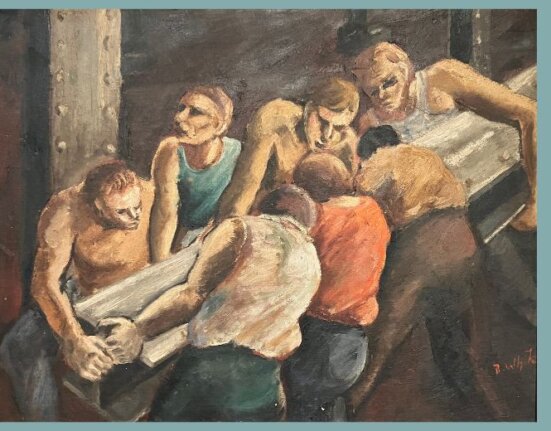

Finally, it had a remarkable impact on the working class generally. As with earlier mass epidemics—famously the Black Death of the fourteenth century—the widespread death created a labor shortage. Before 1793, hired craftsmen had organized short-lived mutual aid societies earlier and even waged a few episodic strikes, notably the 1786 effort of the local printers under the mentorship of Benjamin Franklin.

In the wake of depletion of the work force, lesser supply creates greater demand, raising the price of labor. When this happens the free marketers of all stripes tend to raise a howl for severe regulation to suppress the price of labor. In the wake of the yellow fever epidemic, the patriotic advocates of American freedom from British tyranny took up the use of English common law against dangerous “combinations” of hired workers. After some preliminary threats—if not more—employers successful prosecuted Philadelphia’s journeymen shoemakers for “criminal conspiracy.”

More immediately, though, workers in roughly a dozen trades formed unions in the Philadelphia crafts. The cabinet and chair makers of the city formed a particularly militant body that called a strike in April 1796. Other organizations rallied to their support and the strikers established their own cooperative to earn a living while not supplying their bosses with their labor. In May, they called upon “other Mechanical Societies, viz. House-Carpenters, Tailors, Goldsmiths, Saddlers, Coopers, Painters, Printers, &c &c” to form “a plan of union, for the protection of their mutual independence.”

About this time, John McIlvaine of the printers union published a rhyming address appealing to shoemakers, ie. “cordwainers:”

Speak not of failure, in our attempt to maintain,

For our labor a fair compensation;

All that we want is assistance from you,

To have permanent organization;

A commencement we’ve made, associations we have,

From one to thirteen inclusive,

Come join them my friends, and be not afraid,

Of them being in the least delusive;

A generation before the establishment of Philadelphia’s celebrated Mechanics Union of Trade Associations in 1827, American workers had already established the rudiments of a city central network, the institutional embodiment of a growing sense of solidarity among hired workers.

In that sense, the workers’ attempt to correct the injustices of 1793 have yet to run its course. And the present pandemic has already sparked dozens of labor actions around the country. Watchwords of solidarity and justice take on a new significance, while also resurrecting a time-honored determination.

In the end, this is also the only course to make a civilization capable of managing such crises, of ensuring that workers who need to work through an epidemic will do so with proper protection and those who should not can stay at home without having to worry about rent and sustenance. This is the image of a world that the author of Arthur Merwyn would recognize immediately, one where the safety and security of each is the concern of all.

For this dangerous vision, the employers and authorities are no closer to an actual cure than they were in the 1790s.