One hundred years ago, revolutionary potential was exciting the sensibilities of radicals and counter-revolutionists across the country. In February 1919, the passions and potential of a workers movement was nowhere more powerfully demonstrated than in the Seattle General Strike. Anna Louise Strong was one of the prime chroniclers of the strike, and wrote one of the most memorable lines of the moment:

We are undertaking the most tremendous move ever made by LABOR in this country, a move which will lead

– NO ONE KNOWS WHERE!

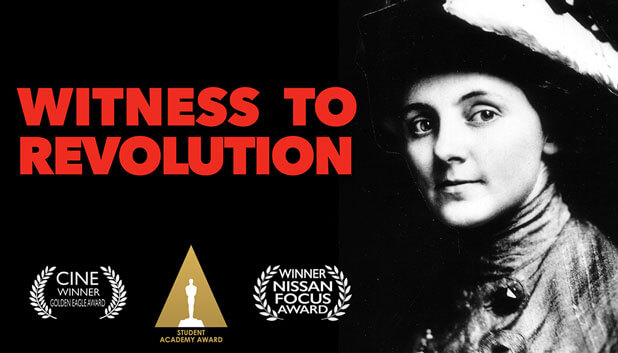

An old film Witness to Revolution, made in the 1980s, deserves the attention of historians for taking us to this moment through the perspective of Anna Louise Strong (1885-1970). Produced and directed by Lucy Ostrander, it has been reissued as a DVD. With powerful images of the era, including rare scenes of the Seattle General Strike, it still has value for introducing this exciting era.

The narration is largely by scholars and friends of Strong, who navigate Strong’s life across decades to introduce her creativity and personality and ideological blinders; these bring perspectives on how a woman of this era managed to create her own pathway in relationship to strong male figures, including Stalin and Mao.

Growing up in Nebraska, the daughter of a minister, Anna’s thirst for knowledge and love for writing led her to a Ph.D. in philosophy at the University of Chicago, an accomplishment which certainly set her apart. Landing in Seattle, a place the film designates “her spiritual birthplace,” in an era of the labor militancy, her eyes were opened more fully to injustice. The film shows how the 1916 Everett, Washington free speech fight and the brutal suppression of the Industrial Workers of the World there by a local sheriff and deputies moved her to more radical perspectives. She covered the murder trials of the Wobblies, charged with murder in a bizarre twist (since Wobblies were the ones murdered–you get a sense of the injustice). Strong began to reject patriotism and commit to a movement, though the film points out that her class status differentiated her from the rank-and-file.

Then in 1919, the Seattle General Strike convinced her that political activism was best realized through direct action of the working class. Strong issued her call to action as lead writer for the Seattle Union Record. While after three days the strike was routed, the hopes of radicals across the world were aroused; for Strong, the hope was never lost. The idea of workers running industry and being the authors of their destiny was a romance that moved her for the rest of her life, especially when those hopes faded with repressive regimes. The film conveys the hope of a generation, long since suppressed.

The film doesn’t ponder the hard questions of how she navigated the trajectory of the failures of the revolutions she supported, but instead celebrates her globetrotting in the Communist world, and her support of successive revolutionary movements. It mildly references some of the contradictions of her positions, but leaves it to the viewer to explore more of these issues in depth. She was exiled in Soviet Russia, staying there for decades, editing a Moscow newspaper, an enemy of the U.S. government. But eventually she was exiled from Russia on charges of being a U.S. government spy, settling in Mao’s China in 1958. She is buried with a fitting monument for revolutionary martyrs in Beijing.

All of this is sure to raise eyebrows even for those who are unfamiliar with the Cold War. The film, in fact, is a useful entry-point for students to understand the hopes for global transformation during this period. The film is short, and doesn’t get into the nitty-gritty. But it still serves as a very personal story of someone transformed into a revolutionary activists by U.S. workers.