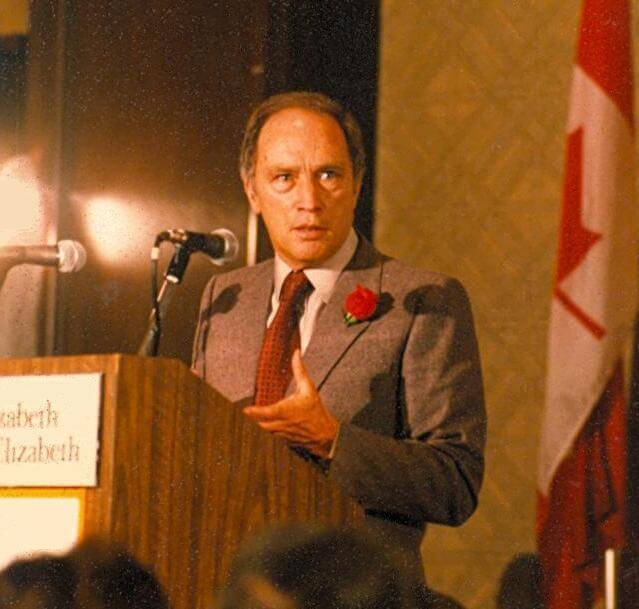

LaborOnline’s no-longer-quite-monthly series on new books in labor and working-class history continues. Christo Aivalis’s The Constant Liberal: Pierre Trudeau, Organized Labour, and the Canadian Social Democratic Left was published on May Day by UBC Press. Aivalis is a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council postdoctoral fellow at the University of Toronto in the history department. He answered questions from Jacob Remes.

For labor historians from south of the border, can you give a short introduction to Canadian Liberal Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau and his relationship to organized labor?

Trudeau’s relationship to labour really picks up in the late 1940s. By this point, he was finished with his formal academic work at Harvard and the London School of Economics (as well as some time in France), and was looking for a meaningful way to contribute in a Quebec society he saw as dominated by regressive social, religious, and economic institutions.

His first major event was the 1949 Asbestos Strike, which was fought by asbestos miners seeking union recognition and safety equipment to protect them from the dust. The strike was illegal and a failure in the short term, but it was—and is still seen—as a watershed moment in the development of modern Quebec that culminated in the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s.

Trudeau after Asbestos felt that Quebec needed intellectuals like himself to change things, and he saw the industrial working class as the motor for that change. Therefore, Trudeau worked with the Quebec labour movement as a freelancer of sorts, giving courses on politics and economics, writing briefs for government commissions, and serving as the labour-sided representative on numerous arbitration panels.

Trudeau felt that through education, Quebec workers could become more cognizant of their political power, and thus usher in a liberal society. At times, this included efforts to link Quebec labour to the democratic socialist Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, but from the mid-1950s onward he became convinced that Quebec’s future rested in small-l liberal parties. At first, Trudeau tried to form two political organizations meant to align Quebec’s liberals, socialists, and unionists in an effort to defeat Maurice Duplessis, but he would eventually back the Liberals as the only path forward, even if he remained critical of the party.

In the 1960s, Trudeau drifted away from day-to-day ties with unions, but when he became Prime Minister in 1968, many felt his historic work with labour—and his election slogan about building a “Just Society”—suggested he would govern from the left. But whereas Trudeau in 1950s Quebec saw labour as the driving force toward liberal democratic progress, Trudeau as PM saw unions as driving unrealistic expectations among the populace in terms of wages, benefits, and social programs.

Many of Trudeau efforts as PM—either through direct legislation like wage controls or in his speeches about Canadians’ unrealistic demands—weakened unions with a view toward installing a trickle-down conception of economics in which his government theorized that workers must first become poorer so that capitalists could create wealth.

In recent years, much has been made about the wage-productivity/profitability gap that started in the 1970s, and in Canada, this was very much an intentional result of Trudeau’s effort to weaken unions and the expectations of working people.

So much of Quebec’s left, including much of its labor movement, is nationalist, but Trudeau was a staunch opponent of Quebec independence. Where does the national question enter into Trudeau’s relationship with the left?

Trudeau and nationalism has been explored in much more detail than Trudeau and labour/the left. Prior to his academic travels, Trudeau could be described as a Quebec nationalist. But from the mid-1940s onward, Trudeau came to see nationalism as a tool of the regressive French Canadian elite, utilized to keep regular Quebeckers from expressing their democratic and economic interests, which Trudeau saw as neither nationalist nor socialist, but liberal. Following the lead of economist Albert Breton, Trudeau argued that workers benefitted most from a market where goods flowed freely across borders. Protectionism merely made them a captive market.

Trudeau’s connection to the left on the national question is complex. At first, Trudeau was sympathetic to the Quebec nationalist assertion that the CCF was too interested in empowering the federal government at the expense of the provinces. This would be seen as detrimental to Quebec’s autonomy within Confederation. But into the 1960s, Trudeau saw the New Democratic Party (the CCF’s successor party) as kowtowing to Quebec separatism by endorsing a two nations theory of Confederation: that Canada is one country with two founding nations of French and English origin.

And while many unions had nationalist tendencies prior to the 1960s, their more strident nationalist turn in the 1960s meant that Trudeau’s ties to labour were strained. For instance, one of the briefs he wrote for a group of Quebec labour bodies was re-drafted with a more nationalist bent.

Into Trudeau’s years as PM, my book looks more at the questions of economic nationalism that were centre stage in English Canada. Here, Trudeau from an ideological level was still a liberal antinationalist, but the political reality of the time was that Canadians were deeply concerned about economic dominance from the USA. In order to prevent the NDP from fully capitalizing on this, Trudeau enacted various policies like the Foreign Investment Review Agency and the National Energy Program. Ultimately, then, Trudeau for his adult life was essentially an antinationalist, but held some sympathies with economic nationalism, even if mainly for political expediency.

For the past year, many liberal and even left-wing Americans have been gazing northward at Pierre Trudeau’s glamorous, liberal son, who seems to represent so much of what Donald Trump is not. Can Pierre’s relationship with the left tell us anything about Justin’s relationship to it?

My book’s conclusion briefly touches upon Justin’s similarities to his father, as well as what that means in the era of Trump. Indeed, both Pierre and Justin mirror one another when it comes to their relatively quick political ascendancies and youthful energies. Additionally, both came about at a time when Canadians were pining for left-leaning change, and were increasingly keen on portraying to the outside world a progressive image.

Differences are many, of course. Justin derived much of his success off of family lineage, while Pierre—despite coming from a rich family—built his own reputation off of decades of study and writing. Also, Justin had no sustained connections to the left or labour before his time in formal politics, whereas this formed the bedrock of Pierre’s activism from 1945-1965. Put another way, whereas Pierre’s relationship with the labour-left was ultimately a combative one, it was more or less organic.

The same cannot be said for Justin. Nonetheless, he has been effective at capturing left energies for a couple reasons. First is that ten years of Conservative rule made his milquetoast reforms seem progressive. Second is that in comparison to the circus-like Trump administration, Trudeau’s faults are seen as either insignificant, or simply go unnoticed.

But I suppose the main lesson is that Justin has benefitted from a time-tested Liberal strategy that goes back to Pierre’s day and earlier: first is to rely on a First-Past-the-Post system (a system Justin promised to repeal, but has reneged on) that essentially blackmails non-Conservative voters into supporting the Liberals. Second is to either adopt some moderate NDP policies, or at least pledge to do so until winning an election. During Pierre’s tenure, this strategy was made explicit in candid behind-the-scenes reports prepared for him and other top Liberals.

Why should American (and other non-Canadian) historians care about Canadian history? Is there something broader about Liberal Trudeau’s relationship with labor and the left that you think can speak across the border?

This is a question many Canadianists grapple with, because we want our work’s significance and quality to stand independent of comparison to other countries, but simultaneously hope that our scholarship manifests a big enough footprint to hit the international (and often, especially) American consciousness.

In my book’s case, its value for Americans and others is that its later chapters explore a period that encapsulates the end of the postwar compromise: a time from the end of the Second World War to the mid-1960s in which many workers saw substantive increases in their standards of living, all while businesses profited, too. But when Trudeau came to power in 1968, this compromise was on shaky ground due to increased industrial capacity in the developing world, spikes in commodity prices, increasingly expensive social programmes, and perhaps most vitally, that workers were seeing gains that began to outpace profitability. In essence, there was in Canada as in many western nations a growing set of contradictions within Keynesian capitalism.

Trudeau, through his attacks on the expectations and rights of workers, was doing his part to pave Canada’s path toward our neoliberal present. This is obviously not identical to the courses we see in the USA and in Western Europe, but it is part of a general historical trend that runs from the late 1960s into the mid-1980s and beyond. Ultimately, American historians might read this book to see how Trudeau’s handing of Canada’s Keynesian crisis compared to what was happening in Washington under both Republican and Democratic administrations.

But beyond the story of western capitalism’s transformation, my book—along with many other Canadian political histories—are invariably of interest to Americans because the issues, events, figures, and institutions we examine are connected to the American political context. For instance, my project explores the question of economic nationalism, which cannot be separated from the United States. Trudeau’s move toward modicums of nationalist control was driven by internal politics to be sure, but Nixon’s efforts to reduce the USA’s trade deficit was met with great worry in Canada, and Trudeau felt alternative courses of action had to be considered as a potential response. Likewise, the discord between Trudeau and Reagan was influenced at least in part by the Liberal’s National Energy Program, a policy unpopular with oil multinationals headquartered in the USA.

Now that you’re done with this book, do you have another project lined up to work on?

In addition to some smaller side projects, including a chapter for a forthcoming edited collection on the past and present of the CCF-NDP, my current focus is a book for Athabasca University Press on labour leader Aaron Roland (A.R.) Mosher.

Mosher—who has never been the focus of a sustained academic analysis—is an important figure due both to his long tenure at the pinnacle of the Canadian labour scene, as well as how his activities help to reflect Canadian labour and left history. Mosher was president of the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees from 1908 to 1952, and was the head of the (All)-Canadian Congress of Labour from 1927 until 1956.

Essentially, the book is laid out into five sections, each exploring how Mosher helped to pioneer actions that forever shaped the Canadian labour movement and wider left. Mosher was not only a trailblazer in popularizing the national and industrial forms of union organization to Canada, but was a founding executive member of the CCF, a public intellectual champion of democratic socialism, as well as a conditional ally to, and then mortal enemy of, the Communist movement in Canada.