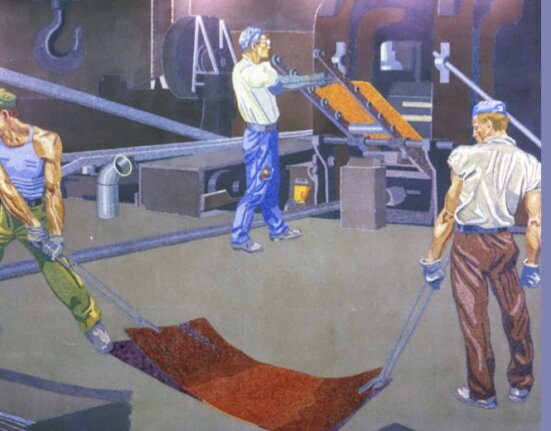

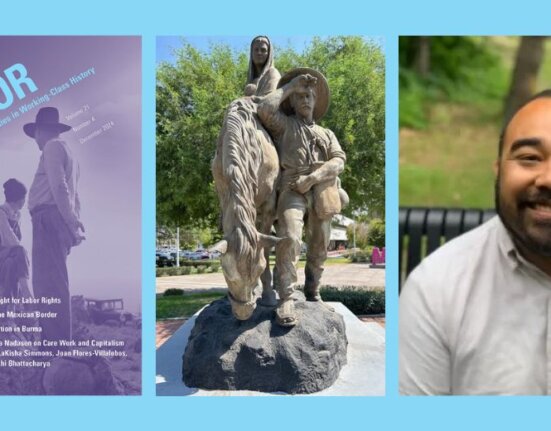

Paintings and sculptures often represent those with power, not the working class. Yet, a current exhibit at Washington, D.C.’s National Portrait Gallery, “The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying America’s Workers,” not only highlights workers, it also invites us to consider the contradictions of work and how it has changed. The exhibit covers more than two hundred years, tracing how artists and documenters have viewed workers.

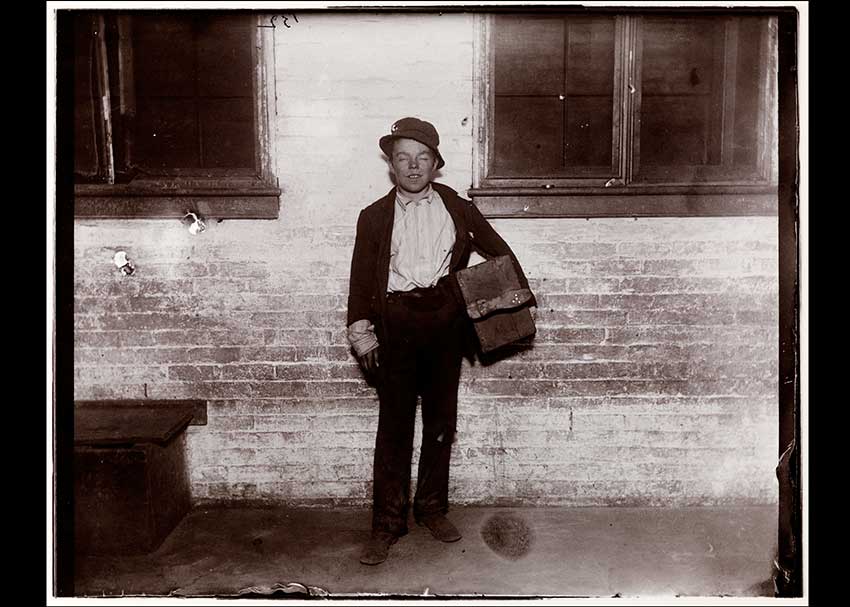

Perhaps because of this historical perspective, the curators seem to define “worker” primarily as “manual laborer,” including factory workers as well as farm hands, newspaper boys, and construction workers. As this suggests, the exhibit skews toward men, though it does also include a “Jolly Washerwoman” and Gordon Parks’s famous portrait of Ella Watson, his version of “American Gothic.” The exhibit also has some notable gaps. Milt Rogovin’s steelworker portraits are absent, as are contemporary photojournalism by Carl Corey, David Bacon, Steve Cagan, and Michael Williamson.

The dignity of workers and the social value of their labor is a central theme, visible in familiar works like Lewis Hine’s photos of construction workers, a Norman Rockwell painting of a smiling miner, or J. Howard Miller’s famous and much-reproduced “We Can Do It!” poster of the woman who would become known as Rosie the Riveter. Less familiar images also echo this theme, including Dawoud Bey’s portraits of African-American small business owners – a barber and the owner of a barbecue joint — from his Harlem USA series, or Shauna Frischkorn’s striking large-scale portrait of “Kean, Subway Sandwich Artist” from her still-developing series, McWorkers.

The exhibit also captures tensions about work, which, as the opening commentary of the exhibit puts it, “influences how Americans measure their lives and how they assess their contributions to society” but can also be “exploitative, painful, and hard.” A number of images, especially documentary photographs by Hine, Jacob Riis, Dorothea Lange, and others associated with the Works Progress Administration or the Farm Security Administration of the 1930s, draw our attention to the struggles of the workplace – to child laborers, to poverty, to physical dangers.

Most of the images are portraits, focusing on a single worker rather than their context or the work being done, which reflects the exhibit’s setting in the National Portrait Gallery. These images take workers seriously, asking us to recognize the valor of their labor, their pride and competence, but also to recognize them as people. As the museum label alongside Frischkorn’s photo suggests, her work “brings our attention to the low social and economic status given to fast-food employees. The ‘unattractive and ill-fitting’ uniforms might be designed to make them anonymous, but Frischkorn pushes against this strategy to reveal each worker’s uniqueness.” Yet even as the exhibit encourages viewers to see each worker as unique, the repetition of the serious, determined, often tired look on so many faces makes clear that most working-class labor is physically exhausting and often dangerous.

This sense of work as struggle exists in tension with the idealistic claim of the introductory panel for the exhibit, that work is the “foundation of the philosophy of self-improvement and social mobility that undergirds this country’s value system.” Despite this statement, the exhibit offers almost no images that suggest upward mobility. Instead, we see portrait after portrait of workers who seem determined and resilient, even though their hard work is unlikely to improve their lot in life.

This may be even more true today, as working-class jobs become more contingent and precarious, than it was during the historical periods that are most represented in the exhibit. Danny Vinik summarized the contemporary and future reality of work in a recent article in Politico:

Over the past two decades, the U.S. labor market has undergone a quiet transformation, as companies increasingly forgo full-time employees and fill positions with independent contractors, on-call workers or temps—what economists have called “alternative work arrangements” or the “contingent workforce.” Most Americans still work in traditional jobs, but these new arrangements are growing—and the pace appears to be picking up. From 2005 to 2015, according to the best available estimate, the number of people in alternative work arrangements grew by 9 million and now represents roughly 16 percent of all U.S. workers, while the number of traditional employees declined by 400,000. A perhaps more striking way to put it is that during those 10 years, all net job growth in the American economy has been in contingent jobs.

In many cases, as Vinik’s article makes clear, contingent workers don’t look much different from the full-time employees they have replaced – in fact, they are often the same people. Vinik frames his essay with the story of Diana Borland, a hospital transcriptionist whose $19 an hour full-time job was reassigned to a contractor that paid her by the line, dropping her hourly wages to just $6.36, less than minimum wage. While she was discouraged, Borland found another job, but she worries about her daughter’s and granddaughters’ future. “Where is the American Dream?” she asked Vinik.

“The Sweat of Their Face” largely ignores changes in work, one piece does make the costs to workers of contemporary capitalism visible. Josh Kline’s sculpture “Nine to Five,” shows a cleaning cart stocked not only with spray bottles and scrub brushes but also the dismembered head and hands of a janitor. The title is ironic, since many janitorial jobs involve evening and night shifts. The piece exaggerates the idea of work as linked with identity, and in the process Kline critiques the dehumanizing effect of contemporary labor conditions.

Among the largest and most striking pieces in the exhibit is a John Neagle’s larger-than-lifesize 1827 painting of Pat Lyon. The almost 94-inch tall portrait depicts Lyon as a blacksmith, standing beside a large anvil in front of a fiery stove, his white shirt rumpled and open at the neck, a heavy leather apron protecting him from sparks, and an almost defiant look on his ruddy face. But it isn’t only the scale that makes this painting so striking. It is the story behind it: according to the online catalog of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, which owns the painting, Lyon was wealthy and successful, which is why he could afford to commission such a large, heroic image of himself, but he asked Neagle to depict him as the blacksmith he once was, telling the artist that he did “not wish to be represented as what I am not—a gentleman.” For many visitors to the exhibit, this image of a wealthy man as a proud laborer is the first work they encounter. It is at once odd and fitting that the first image treats work as an idealized role, not as a real, material and social act.

In the early 21st century, it’s almost impossible to imagine a successful businessman asking a painter or photographer to depict him as, say, a Subway sandwich maker. The conditions of work in the contingent economy not only undermine what the Portrait Gallery calls “this country’s value system.” They also undermine the potential for workers to find pride and satisfaction on the job. That may be one reason Frischkorn refers to her photos of fast-food workers, which mimic the style of Renaissance portraits, as “ironic.” The images emphasize the workers’ humanity in an era when dignity on the job has become out of reach along with expectations that hard work will pay off in “self-improvement and social mobility.”