Sexual harassment is both a labor and gender justice issue. After all, the workplace is the epicenter of women’s recent outrage about sexual harassment and assault. Hollywood titans, respected reporters, and celebrity chefs all used their power over women’s paychecks in order to gain power over their bodies. Women (and some men) have responded by speaking out individually, yet their inspiration is decidedly collective; strength in numbers is what’s fueling the revelatory headlines. Women’s #MeToo tsunami, in fact, is perhaps the largest collective labor action of the early twenty-first century. In order for this riveting social movement to have a lasting impact, #MeToo solidarity must impact more than the elite. Workplace culture and expectations must shift for average, working-class women, too.

Women have been struggling to make the workplace safer for decades. They first made sexual harassment an issue in the 1970s when feminist workers and rape crisis activists united efforts, according to one recent account. By 1980, it seemed there was progress. Under the leadership of Eleanor Holmes Norton, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) first issued explicit guidelines on sexual harassment. But then Ronald Reagan appointed Clarence Thomas chair of the EEOC in 1982, and he led the agency’s back peddling, well before Anita Hill accused the Supreme Court nominee of sexually harassing her in 1991. Hill endured fraught public scrutiny of her claim, and Thomas’s appointment laid bare how little headway women had really made.

It’s worth examining what has changed to make this workplace issue burn so brightly in 2017.

First, of course, there’s the Trump factor. Many women were stunned and appalled when Trump won the election despite bragging about groping women. The fact that his opponent was the first viable female candidate made the loss all the more bitter. Millions turned out last January for the Women’s March; their sea of pink pussy hats marked the original #MeToo moment. Incensed, many women have begun to speak out about the injustices they have kept quiet for too long.

But there are larger historical developments at play. In an era of heightened rights awareness, the Black Lives Matter and immigrants’ rights movements have led the way, launching fresh and innovative attacks on structural racism well before the 2016 election. Millennials are at the forefront of these fights, waging movements online and in the streets, well outside the traditional civil, labor, and human rights organizations.

Millennial outrage may be providing the energy behind the current tipping point on sexual harassment, too. After all, millennials are now aged 18 to 35 and so have come into their own in America’s workplaces. This generation of women must hold jobs; few really have a choice. They grew up with moms who worked, and recent research shows that young people are more accepting of working mothers today than even those in the 1990s. Nearly half of mothers are now the sole or primary breadwinners in their families. If paid work is something you and everyone else expects of you in life, then it’s all the more intolerable when men routinely make the worksite a dangerously sexualized realm. Millennials just aren’t taking it, and many older women find themselves inspired by these young women’s indignation.

Can women harness the solidarity impulse of the millions of women who posted the #MeToo hashtag? Will millennials finish what earlier generations started and build enduring change on the job? Their success is far from certain. Elite and professional women are receiving the lion’s share of the attention, and few long-term solutions are being discussed. An effective social movement on workplace sexual harassment can’t stop there. It must broaden to include women of all backgrounds and should channel the outrage into organizational and legal transformation.

While Hollywood actresses and elite journalists dominate the headlines about sexual harassment, research reveals that working-class women are the most likely victims of workplace sexual intimidation and assault. The Center for American Progress looked at a decade’s worth of EEOC claims and found that waitresses and retail clerks are the most likely to face sexual harassment on the job, followed closely by manufacturing workers and those in health care. A full 80 percent of restaurant workers deal with harassment on the job, including two-thirds who have to fend off management predators. Women are the most likely to work low-wage jobs where power imbalances are sharpest, and that’s especially true for women of color.

Effective solutions to workplace sexual abuse must empower women on the job, especially young, working-class women who are the most vulnerable. The Restaurant Opportunities Centers (ROC) United is playing a leading role, demanding an end to the sub-minimum wage that leave so many tipped workers vulnerable to intimidation. Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin have even joined the group’s crusade, speaking out and posting viral videos on the topic.

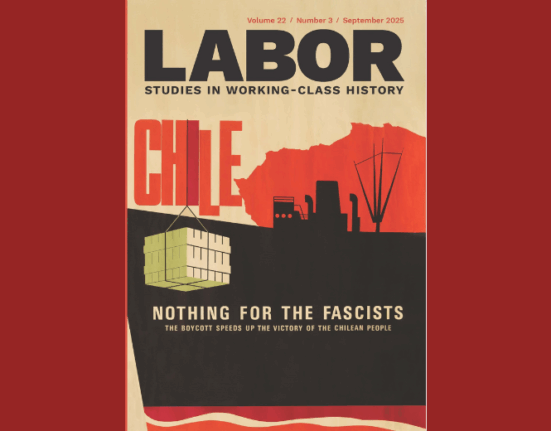

Union women, too, can demand that their organizations lead the nation’s response on sexual harassment; after all, more than half of the nation’s union members will soon be women. The hotel workers union in Chicago found that well over half of hotel workers reported harassment from guests; their #handsoffpantson campaign demands that management equip hotel maids with panic buttons and ban guests who sexually harass a worker. After many female janitors in California found themselves alone at night in empty buildings alongside abusive male managers, the United Service Workers West won contract language and a law requiring cleaning and security employers to offer training on sexual harassment.

A union isn’t an automatic defense against sexual harassment. After all, some unions have been at the center of the recent storm. The SEIU and the AFL-CIO have both ousted top male staff for workplace sexual abuse. Unions also have a fraught relationship to the issuebecause their duty of fair representation requires them to defend workers accused of sexual harassment, even when another union member makes the allegation.

Nevertheless, women union members can — and should — take a leading role, and sexual harassment is an issue through which they can build power for all working women, not only the 10 percent who hold a union card. They could take a cue from the millennials’ movement against campus sexual assault, for instance, and partner with the new online group Callisto to build an online tool allowing women workers to document harassment and unite against repeat offenders. They could also convene a big tent coalition of unions, workers’ centers, policy experts, and women’s groups to strategize the next best legislative and policy steps.

Many women say they aren’t surprised by the breadth of the accusations that dominate the news headlines. As the #MeToo hashtag wave made clear, millions have endured this in some form. What’s new is that we are openly recognizing and naming the hidden dangers that women have long navigated at work wordlessly and alone. The #MeToo moment demonstrates collective action’s raw power. The question is whether women will be able to turn their next-generation solidarity into a broad-based and inclusive movement that can win enduring workplace transformation.