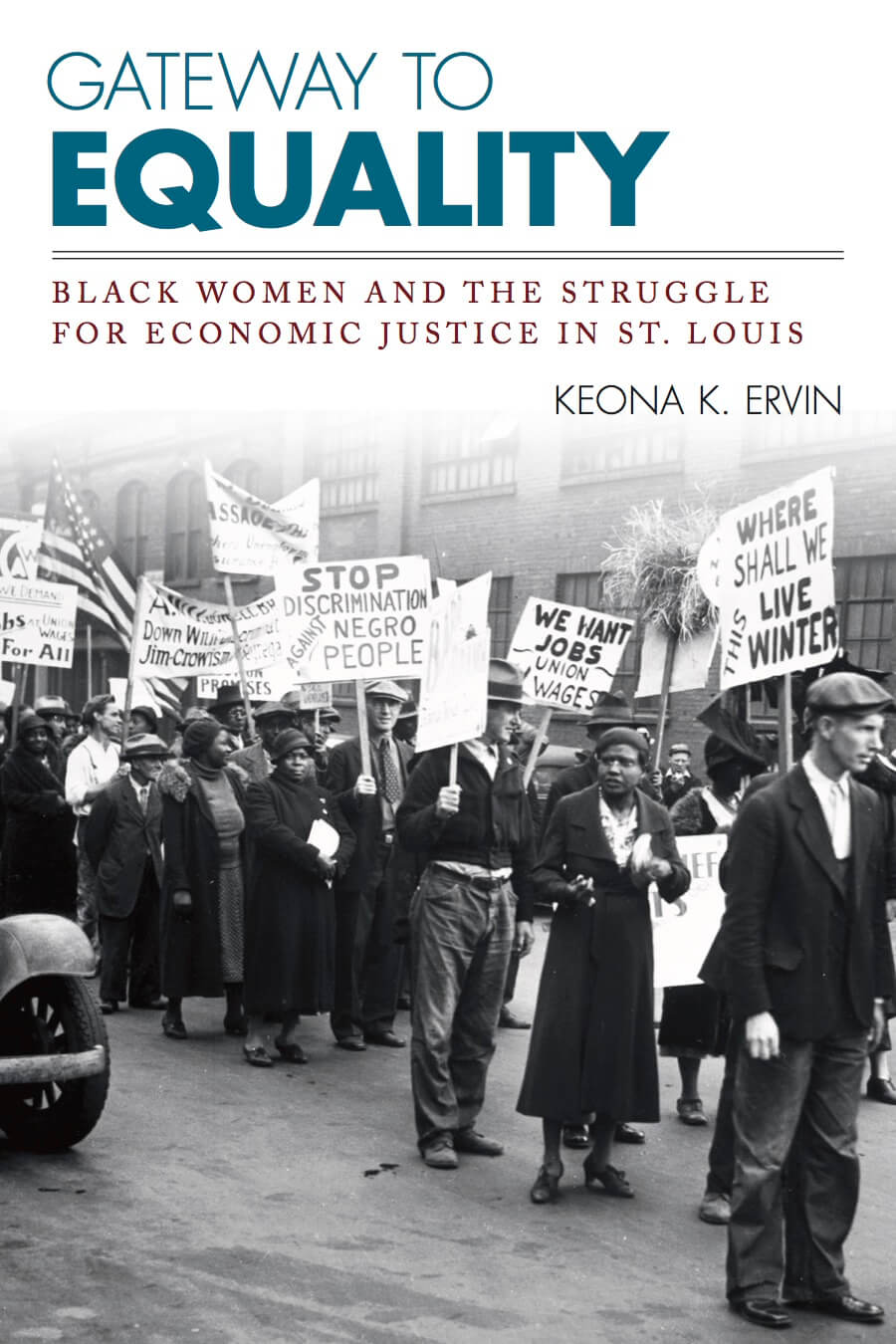

Candace Borders, a recent graduate of Washington University in St. Louis, interviews Keona K. Ervin on her new book Gateway to Equality: Black Women and the Struggle for Economic Justice in St. Louis (University of Kentucky Press, 2017).

Ervin is Assistant Professor of African-American History and Faculty Affiliate in the Department of Black Studies at the University of Missouri-Columbia. Ervin is a recipient of the Career Enhancement Fellowship from the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation (2015) and the Higgins Quarles Dissertation Award from the Organization of American Historians (2008). Ervin’s work has been published in International Labor and Working-Class History, the Journal of Civil and Human Rights, and SOULS: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society. Ervin serves on the Board of Directors of the Labor and Working-Class History Association. Follow her on Twitter @KeonaErvin.

Candace Borders: How did you come to this project? What are some of the experiences and factors that motivated you to write a book about Black women and their struggle for economic equality in St. Louis?

Keona Ervin: The idea for this project originated in a series of conversations I had with labor and civil rights activist Ora Lee Malone while studying for my doctorate in history at Washington University in St. Louis. For a final assignment in her course on oral history methods, my advisor, the late Dr. Leslie Brown, assigned a research paper based on the life of a participant in the St. Louis civil rights movement. I chose Ora Lee Malone after finding her words in an oral history collection. I was deeply intrigued by Malone’s reflections, and, later, I was thrilled to learn that Malone was eager to speak with me.

Having been steeped in a Black freedom movement narrative associated with voting, desegregation, and charismatic Black religious and secular male as leaders, I learned about alternative approaches at Ora Lee Malone’s kitchen table. Born in Mississippi and later settling in Alabama, Malone framed the Black struggle for freedom as a local one that prioritized the rights of workers. Moving to St. Louis in 1951 and soon landing a job as a pieceworker at the California Manufacturing Company, a producer of men’s apparel, she later led a successful unionization drive under the jurisdiction of the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU). From that point on, she became one of the most active organizers of her day, widely recognized as a champion of the working-class, women’s political leadership, and racial justice. I found synergy between Ora Lee Malone’s narrative and the scholarship I was reading at the time, including the works of Tera Hunter, Robin Kelley, George Lipsitz, Clarence Lang, and Leslie Brown.

Borders: One important aspect of your methodology is to study Black women’s activism in the decades prior to the 1950s and 1960s. Why was this an important move to make?

Ervin: It was during these earlier decades that Black working-class women’s politics helped to inaugurate what George Lipsitz calls “Age of the CIO,” which was based on the idea that workers should have access to institutional and social apparatuses that guaranteed dignity. The decades prior to the 1960s witnessed domestics, pecan shellers, the unemployed, clerks, defense plant workers, garment factory employees, public housing tenants, and welfare recipients organizing for economic justice. Their political labors indelibly marked and, in crucial ways, defined Black political agendas during these years. Manipulating organizations that stood at the forefront of the battle to defend the economic rights of the Black working-class, namely radical labor entities like the Communist Party (USA), the NAACP, the Urban League, the March on Washington Movement, some industrial unions, and other local groups, Black women laborers built a powerful case for the political implications of their economic lives. This earlier period was significant because of the ways that Black women’s economic experiences became a defining agent in the formation of the coalitions that engineered a working-class-inflected freedom agenda.

I also highlight the earlier period to provide a kind of prehistory of antipoverty and racial justice campaigns of the 1960s. In the book, I suggest by way of conclusion that battles in the late twentieth century were legible as working-class mobilizations because of the groundbreaking work of Black women’s labor politics over the past three decades. The St. Louis 1969 rent strike, for example, was a culminating episode in an organizing tradition that had firmly situated Black women’s economic politics as a constituent part of working-class struggle.

Borders: In your book you argue that Black working women struggled for “economic dignity,” a term that encompasses much more than simply a decent wage. Tell us more about the significance of utilizing this expansive framework to better understand Black working-class women’s labor activism.

Ervin: The notion that the traditional ways of defining labor history and activism are insufficient for capturing the history of Black women’s activism has long been an underlying conception in the field of Black women’s history. I draw upon this body of work as well as “new” labor history scholarship to make the point that while wages and working conditions were deeply important, so, too, were other concerns. Gateway to Equality defines Black women’s labor activism as a set of projects designed to form a collective relationship with employers, make dignity tangible in contractual and casual economic arrangements, and politicize breadwinning and economic contribution to family and community. Through creative use of institutions, coalition, migration, testimony, everyday resistance, and self-organization, Black women dissidents waged a fight for a living wage, fair employment, decent employment conditions, food, housing, regard, and access to leisure and accommodations. Their expansive understanding mobilized concerns about the broader public sphere’s concern for and commitment to Black women’s survival and the well-being of all workers. An expansive outlook also helps us to rethink the ways that we conceptualize and categorize political methodologies. Unionization was by all means important, but it was by far not the only form. The women I studied drew upon an organizational model that created quasi-unions out of community organizations.

Borders: Throughout your book, you argue that a central component of these women’s economic activism was to make their political subjectivity legible. Tell us more about this tactic. Why was this approach so important?

Ervin: By discussing this theme, the book seeks to make the gendered character of Black economic self-determination visible. I explain that Black working-class women were situationally central to movements. One the one hand, their mobilizations served as an axis around which movement-making turned, and, on the other hand, their economic politics routinely confronted a set of misapprehensions about their political subjectivity. Many women navigated political cultures that, for instance, attributed Black women’s political actualization to sources external to women themselves or barred women from becoming spokespersons or political leaders in terms of those who set agendas, even when campaigns were so clearly based on their own issues. Situational centrality, I point out, indicated both a kind of political marginality and a form of political power.

One of the key ways that Black women workers resisted this practice was by disrupting the tendency to position the disaffected Black male working-class subject at the center of Black economic liberatory projects. Some formed alternative organizations to provide space for women to question male leadership, while others found ways to push organizations to amend their practices.

Borders: Each chapter analyzes key figures and moments of activism that made up Black women’s economic activism in St. Louis’s history. How did you go about choosing which actors and moments to include and give voice to in your text?

Ervin: The sources available to me at the time necessarily determined the stories that I could tell. A diverse set of sources including personal collections, institutional and organizational records, oral history, music, playbills, literature, and newspapers made it possible to recover Black women workers’ political labors. I selected figures and case studies that illustrated women’s insistence on economic dignity and the breadth of approaches that women employed. I wanted to illuminate the variation within Black women’s work and complicate monolithic readings of their paid labor.

My book opens with the Funsten Nut Strike of 1933 in which working-class Black radical women led a strike of two thousand predominantly Black women industrial workers in the East St. Louis and St. Louis nut shelling industry. It concludes with a brief discussion of the 1969 rent strike in which public housing and welfare rights activists targeted the St. Louis Housing Authority. These two moments, I argue, helped to put St. Louis on the proverbial map as a site of transformative Black working-class struggle. Campaigns in the intervening decades such as the efforts by domestic workers to standardize their household labor and garment workers’ campaigns to reimagine progressive unionism, linked them together. Ultimately, the case studies that I selected were those that demonstrated how St. Louis was a unique incubator for Black women workers’ political influence, particularly in matters pertaining to economic rights.

Borders: What type of impact do you hope your work will have on the existing literature on Black women’s history and political activism in the United States? What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

Ervin: My hope is that my book will extend and amplify the scholarship by drawing attention to the historical significance of Black women’s labors for economic dignity. I hope that the book makes clear the significance of gender to Black working-class politics and culture, in general, and the labors of Black working-class women to the local and national push for labor rights and racial equality, in particular. Gateway to Equality tries to answer how, why, by what means, and at what moments Black workers, especially Black women, made their economic lives and survival a matter of political import. In a large sense, the project is about how Black workers’ class politics, particularly those designed by women, alter the ways that we tell the history of organizing for economic and racial equality. I wrote the book to join a group of historians who are illustrating that the labor of Black women workers’ labors enacted class struggle and formed political cultures that supported but also critiqued the ways that movements understood democracy, equity, and justice.

Posted in conjunction with and with permission from Black Perspectives.