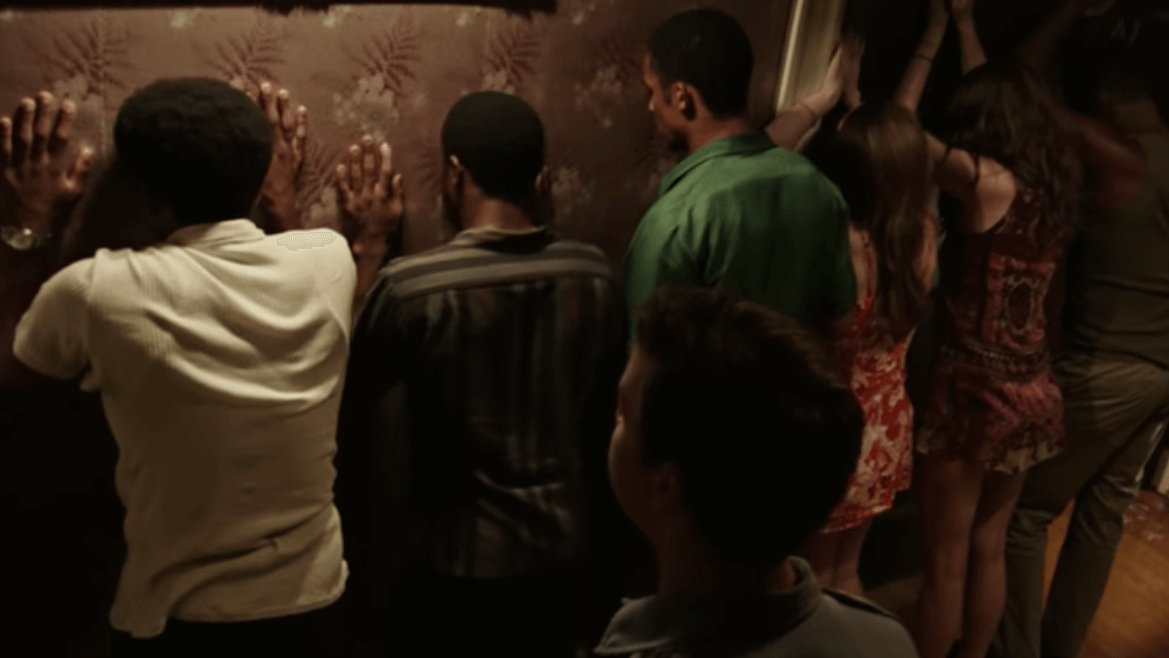

Just a few days after white supremacists marched in Charlottesville, my husband and I went to see Kathryn Bigelow’s film, Detroit. Set amid the 1967 uprising 50 years ago this summer, the film focuses primarily on the brutal torture and the murder of three black men by police officers that took place that week at the Algiers Motel. Because it so powerfully and intimately dramatizes the racial hatred and injustice that has defined far too much of this country’s history, the film was a fitting end to a terrible week. In an era when police officers keep shooting young black men whom they see as threatening, and when jury after jury acquits those officers, no matter how clear the evidence that their victims posed no threat at all, Bigelow puts us inside a sustained and horrific example of police brutality and, true to history, refuses us the relief of a just verdict. To see this film after the events in Charlottesville and the President’s disturbing insistence that the “alt-left” was as much to blame as the bigots bearing assault rifles, waving swastika flags, and chanting racist and anti-semitic slogans, was especially sobering. I was depressed before seeing the film. I could hardly move as the credits rolled.

We went to see Detroit in part because I had been studying fiction, poetry, and films about that city as I researched a book on deindustrialization literature. Detroit is the iconic Rust Belt city, and its deteriorating landscape and long-term economic and social struggles have drawn attention from photographers, filmmakers, advertisers, poets, and fiction writers. In many ways, stories about Detroit are typical of deindustrialization literature, centered on how people and communities continue to wrestle with the long-term effects of economic decline. But there’s one crucial difference: while all Rust Belt cities have been marked by racial division and injustice, more than any other city, Detroit is defined by race. Where other deindustrialized cities trace their transformations to plant closings, in Detroit, decline is almost always linked to the uprising of 1967 and the white flight that it spurred.

Yet, as Tom Sugrue has noted, the history of racial tension in Detroit began long before the riots, and it was always entwined with economic struggle. In the opening animation sequence of Detroit, we are reminded that the Great Migration of African Americans was driven by the economic hope of factory jobs, not by – or at least not only by – a desire to escape the Southern racism. African Americans coming to the city in search of good jobs faced segregation and discrimination, patterns that Angela Flournoy captures well in her 2015 Detroit novel, The Turner House. But as Sugrue has shown, both racial divisions and economic inequality grew when Detroit’s factories moved out of the city to suburbs like Warren and Livonia. The African Americans who burned buildings and looted businesses in 1967 were frustrated not only by racial prejudice but also by economic limitations, even though, as Sugrue points out, they were not “the poorest or the most marginal. It was folks who were slightly better off and slightly better educated and more tied into the city’s labor market than the poorest residents.” Detroit’s history reminds us that conflicts over race are often also class conflicts.

Fifty years later, African Americans still lag far behind whites economically. They have higher rates of unemployment, poverty, and incarceration, less access to good health care or education, and lower rates of home ownership and less wealth. When we say that Black Lives Matter, we’re not talking only about the right to be safe from police violence. We’re also talking about the right to earn a living, to have access to decent health care, to get a good education, and to vote. Like the African Americans who rioted in Detroit in 1967, African Americans today – along with many other people of color – have good reason to be angry, frustrated, and doubtful about the integrity of government officials, elected or employed.

While racism clearly exacerbates class struggles for African Americans, we also need to understand how class and race work together in shaping the ideology of white supremacism. Most working-class white people are not neo-Nazis, or do they identify with the alt-right. But it seems likely that many of those who claim that whites are the most frequent victims of discrimination, that immigrants are taking “our jobs,” and that Black Lives Matter is a terrorist organization are motivated in part by a sense of economic vulnerability. As Bryce Covert wrote in The New Republic, the “ethno-nationalist agenda” is, to a large extent, “about protecting white jobs and white people.” That some of the alt-right’s violence, blame, and bigotry comes as response to the economic shifts of the past fifty years, which have undermined the economic stability of so many working- and middle-class people, does not excuse it. But economic anxiety plays a role here, and just as with the economic and social struggles of people of color, some of that anxiety (though clearly not all) reflects real changes. Wages have stagnated, job security is hard to come by, home foreclosures continue, and pension plans have defaulted. These struggles affect not only people displaced from industrial jobs, but also many in the middle class. Indeed, like the African Americans who rose up in Detroit in 1967, many in the alt-right are employed and educated, and these groups are actively recruiting on college campuses.

Unfortunately, that the alt-right and many of its targets share class interests doesn’t offer much reason to hope. Don’t expect a multicultural working-class revolution any time soon. Instead, as Keri Leigh Merritt pointed out in a piece on the Moyers & Company blog recently, the elite are once again using divisions of race and ethnicity to foment conflict within the working class and distract us from their machinations. In his infamous interview with the American Prospect’s Robert Kuttner, Steve Bannon sneered that he had manipulated the left into staying “focused on race and identity,” allowing conservatives to claim ownership of the economic agenda. Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne, Jr., suggests that this may explain Trump’s refusal to indict the alt-right: “dividing Americans along racial lines while fueling a fight on the left over identity vs. class politics will leave him a winner.” The pattern is reinforced not only by Trump’s nationalist economic rhetoric but also by the narrative, too often supported by those on the left, that blames the white working class for Trump’s election. And it is echoed in the insistence of some progressive commentators that the sole explanation for Trump’s popularity is racism.

To call commentaries that emphasize the role of economic anxiety “equivocating” or a simple refusal to “face the blatant racism that fueled [Trump’s] popularity,” as Roxane Gay does in a New York Times column, suggests that we must choose between race and class. Did racism play a role in Trump’s success? Absolutely. Is it the only cause? Of course not.

Some seem to think that progressives cannot do more than one thing at a time. If we’re organizing against racism and bigotry, presumably, we can’t also advocate for economic justice. If we focus on the economy, we must not care about racism. But to create real change, we need to push for solid strategies for economic justice AND stand up against hatred and for a more inclusive, more equal America. Can we do both at once? As Obama told us, yes, we can. We must.