Prof. James N. Gregory has performed a real service with his “Radicals in the Democratic Party, from Upton Sinclair to Bernie Sanders” (re-posted to Labor Online August 4) It provides an opportunity to explore what he raised—and chose not to raise—with reference to the current election.

The article acknowledges that “’progressive’ has become a vague identifier, but the term is used so loosely as to be almost meaningless,” but it uses “radicals” and “leftists” as synonyms while defining neither. From context, though, it uses these words to describe half of “the marriage between radicals and the Democratic Party.” Consciously or unconsciously, this Orwellian usage effectively purges those radicals and leftists outside of that marriage, and smuggles its conclusion into the premise.

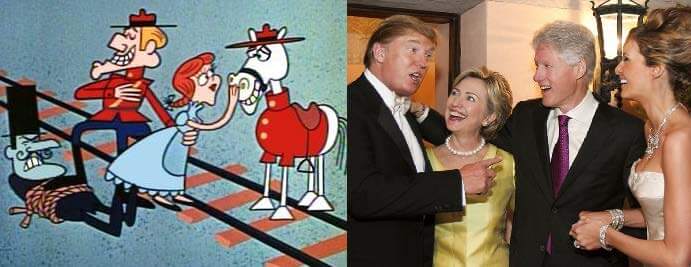

Beyond the Cartoon Marathon

When I watch election coverage, it strikes me how much it resembles a 24/7 multi-year cartoon marathon pitting Dudley DoRight against Snidely Whiplash. Here the viewer-consumer-citizen gets only to decide which of the two politicians they can see more comfortably as Dudley… or, more usually, as Snidely. We are urged to forget that office-seekers are inclined to tell us what will make us buy more of what they’re selling, and that a newly elected president doesn’t just come into office and implement an agenda based on their desires.

Scholars tend to set aside their tools when they go to a sports event or enter a place of religious worship… or address contemporary politics. But we should not do this when it comes to examining the current spectacle of political gamesmanship. Professional history began in the distrust of mystical nationalist literature and rejection of views of the past that claimed the fate of the world would be turned by “great” individuals any more than on the whims of deities.

Many factors will shape what a presidency does and nobody knows what the next four years will present. Who would have guessed about the cataclysmic changes wrought by the Bush administration? Yet, we can understand the context in which those factors will be interpreted. The same legions of advisors, functionaries, consultants, and lobbyists will respond to events much the same way whether the incoming president will be a Democrat or a Republican.

While the newcomer will bring in their own “team,” it will constitute a relatively minor factor of their own choosing. Yet, we can say a great deal about the character of that team as well, because these will reflect the preoccupation of keeping the big donors. These are more-or-less a matter of record available to the public in sites such as OpenSecrets.org, though they provide only what information candidates must disclose. Yet, the data is revealing—though not as much as the reluctance of media and parties to discuss it.

The Courtship of the 1930s

Gregory’s article starts his discussion of the “the marriage between radicals and the Democratic Party” with the 1934 gubernatorial campaign of Upton Sinclair as a Democrat in California, describing it as a response to Norman Thomas’ poor showing as an independent Socialist two years before. This approach crushes mass political insurgencies and a militant labor movement across North America into the singularity of a campaign in one state.[1]

The article asserts the “obvious” lesson that “radicals could do much better working inside the Democratic Party than trying to win elections on their own.” However, since Thomas lost as a Socialist and Sinclair as a Democrat, how did the latter possibly represent an improvement on “trying to win elections”? And, while we know that Democrats have taken serious pains not to elect anybody with something like Sinclair’s platform, we don’t know how what mass independent organizations might have achieved over the intervening eighty years.

Indeed, most of us—at least in a non-election year—would acknowledge that independent social movements are one of those terribly important factors in shaping political life and making policy. Of course, the challenge from the Democratic perspective aims to minimize pressures imposed from the outside, which is why shrewd observers have called the Democratic Party “the graveyard of social movements.” The article solves the problem by rendering the question invisible.

But an undeniably brutal and involuntary reality lies behind that “marriage.” Democrats, including darlings of the progressive or liberal wing such as Woodrow Wilson and A. Mitchell Palmer initiated an overt, active, pernicious and vicious repression of those organizations before and after World War I. With the expurgation of strikebreaking, prosecutions, mass deportations without prosecutions, incarcerations, and executions, we are to assume that this fanciful “marriage” involved some ideological seduction. This continued into the New Deal when Roosevelt reauthorized the FBI domestic spying, a project that targeted militant labor.

This approach recurs in mentioning 1948, when “the left lost all credibility” by running FDR’s former Vice President Henry Wallace. To say this without mentioning the political psychosis that was the post-World War II red scare takes oversimplification into dishonesty. And that madness did not begin as “McCarthyism” but in the policies of Democrat Harry S. Truman.

The Nuptuals of 1972

Prof. Gregory’s piece states—remarkably for those of us who lived through the intervening years—“The framework of 1972 has given radicals ever since a stake in the Democratic Party.” You can probably find some people who call themselves—or are being called—“radicals” anywhere in the political process. However, vast numbers,

particularly among the young, expressed a pervasive mistrust of the Democrats, generated by the foot-dragging over civil rights, lingering suspicions over the murders of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X and various local leaders of the Black Panther Party. The party regained none of this with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s jihad in Vietnam, culminating in the ruthless crushing of the 1968 challenges ensure the coronation of his hand-picked successor, and the additional concerns about the murders of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy.

But the “ever since” dimension about 1972 is simply mind-boggling, since the single most important outcome of the McGovern campaign had been that Nixon crushed it with a tsunami of big money. Only weeks after the election, Democrats hostile to McGovern formed the Coalition for a Democratic Majority, hoping to jettison McGovern’s politics, revive the party’s Cold War agenda, shelve the War on Poverty put enforcement of civil rights legislation on hold—Daniel Moynihan suggested treating the subject with “benign neglect.” Democrats associated with the American Enterprise Institute—Jean Kirkpatrick, Irving Kristol, Robert Novak, Richard Perle, Ben Wattenburg, Paul Wolfowitz and others—helped push the party’s leadership to the right. Among other things, the new reforms eliminated distinct caucuses to keep the TV cameras covering the convention from “interest groups”—women, blacks, Hispanic, labor, etc.—that kept big money away. In short, the framework of 1972 did not vindicate a progressive presence in the Democratic Party but the concerted and cynical institutional stifling of any voice it ever had.

Determined to avoid looking too “liberal,” the Democrats avoided any substantive progressive initiatives under the Carter administration, and essentially caved to the

incoming administration of Ronald Reagan on all major questions, from trickle-down economics to the revival of Cold War militarism (and spending)… and, of course, a studied obliviousness to increasingly obvious major environmental issues. With movements for labor justice, civil rights and women’s rights having abandoned an independent course, the Democrats could yawn at their concerns right alongside the Republicans.

When the party failed to get enough of these constituencies for change to unseat Reagan in 1984, the Clintons and others formed a Democratic Leadership Council in 1985 to encourage candidates untainted by liberalism and to continue moving to the right in search of those Nixonian fleshpots they desired.

Clintonian Bliss

Amidst talk of a “peace dividend” at the end of the Cold War and a major reallocation of resources, the “New Democrats” elected Bill Clinton president. At the start of his administration, he found himself a pit of his own digging and expressing his frustration in an Oval Office meeting: “I hope you’re all aware we’re all Eisenhower Republicans…. . Here we are, and we’re standing for lower deficits and free trade and the bond market.” All talk of a “peace dividend” disappeared as the quest for new enemies abroad began, with the War on Drugs continuing with renewed vigor. At home the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act set the country on a course to having a larger proportion of its population incarcerated than any other country on the planet. These would be mostly poor, young black males—“superpredators” who could not be rehabilitated, as Hillary Clinton and others rationalized it. Still, the Democrats did begin to become competitive with the Republicans in terms of fundraising.

Attitudes to the American labor movement reflected all these changes. Earlier, Democrats claimed to see the unions as an essential factor in promoting a general prosperity. Since the 1990s, though, the party passed from a kind of benign neglect through an agnosticism into an overt hostility. Under Clinton’s tutelage, Arkansas Democrats made hostility to unions part of their plan for trickle-down policies to promote prosperity and jobs. Hillary Clinton’s current pick for vice president, as governor of Virginia, embraced the so-called “right-to-work” laws (and “right-to-life”), which rather demonstrates the importance of these things have to her and to the Democratic hierarchy in making major appointments. The recent campaign through the rust belt focused on “Jobs” without mentioning “unions.”

The Nader Canard

When ignoring inconvenient bits of history doesn’t make the case, fictions are the next resort. Whether intentionally or not, Prof. Gregory refers to a brief martial spat in 2000 in which radicals went for Nader, costing the Democrats the presidency. In Florida, with his own brother’s people doing the official count, George W. Bush defeated Al Gore by only 534 votes. The truth is that the Green, Natural Law, Reform, Libertarian, Workers World, Constitution, Socialist and Socialist Workers Parties all got more votes than that.

Have we ever heard Democrats whining that the Workers World Party cost them Florida? No, the propaganda mill cynically wove this fantasy around Nader for the political purposes of discrediting what they saw as their greatest long term threat.

But the numbers tell the tale here. Twelve times as many Democrats voted for Bush than Nader. 191,000 self-labeled “liberals” also went to Bush, as opposed to fewer than 34,000 to Nader. Half of all registered Democrats—roughly a million of them—sat out the election, and this does not include the estimated 94,000 voters, mostly minorities, the Republican state government removed from the rolls before the election with no challenge by the state’s Democrats. Gore even lost his own Tennessee and Clinton’s Arkansas. Still, as a media recount a year after the election demonstrated, Gore had actually won Florida—and the national election—but had been crippled by a party apparatus incapable of mounting a serious legal challenge to the official count. Democratic ineptness—not Nader and the Greens—cost them the 2000 election.

Essentially, the Democrats had no real agenda separate and apart from that of the Republicans for which they might fight. Indeed, after 9-11, the Democrats lined up behind Bush’s draconian policies abroad and at home. Given the repeatedly demonstrated Bushiness of the Democrats, I would have no problems embracing it if Nader had denied them the White House, if it were so.

It just wasn’t.

Money & Media in Politics

The American Presidency Project summarizes the trend in the price of presidential campaigns. [2] The combined cost did not break a million until the “Stolen Election” of 1876 and hadn’t gotten to $3.5 million at the turn of the century. It only took until 1920 to double to $7 million. By 1960, it got just over $20 million, then $60 million by 1980, $135 million in 2000, and way over a billion in the Obama years. The Center for Responsive Politics notes that, in 2016, the two parties spent a billion well before Clinton and Trump emerged as the party’s candidates. What had always been a rather exclusive rich man’s game has increasingly become an ever-richer man’s game.

It takes a studied psychological disconnect not to see the relationship between this fact that the greatest polarization of wealth in the history of human race has resulted. Or to pretend that voting in validation of this process will address the problem, however incrementally.

The rightward drift of both parties less reflects a shift in public opinion than the important of money in electoral politics, and the importance of money comes directly from the rise of mass media as a means of political advertising. Media is ultimately ideological, only in that its owners deeply believe that they just don’t make enough money. The bipartisan deregulation of corporate media in the 1980s escalated the pace of this trend until, by 2012, half a dozen corporations controlled 90% of the nation’s media.

From the days the Reagan White House began choreographing its own coverage, there has been an increasingly cozy relationship between media and the politicians they cover. Most directly, media determines for us who should get air time and be regarded as a “serious” contender for the office, and, ultimately, this generally winds up being those with the best funding.

And on what do they spend that funding? Media advertising, right? No conflict of interest there.

Because elections are to media what Christmas is to malls, they stretch the selling season longer and longer, even as the rest of the industrial world looks on in wonderment. Media creates and shapes the elections and its controversies, and it does so not to enlighten or clarify but to attract viewers.

Eager to win election, parties have turned to the kinds of candidates and the kind of campaigns that suit the media as well as bring in money from big donors.

Because the Democrats have actually flanked the Republicans over time (mostly by, as President Clinton suggested, becoming Eisenhower Republicans), the Republicans have pursued a media-oriented strategy to their peril, stumbling from Dan Quayle through Sarah Palin to Donald Trump. His very well-planned transition from celebrity of reality TV to presidential candidate involved his cynical and puerile ranting over Obama’s birth certificate. The media takes no responsibility to point out that this was a long settled non-issue, and his ability to stir up the bile gets viewers. In fact, they’d put a camera in front of him whatever he’d say, so that even when it pretends to be exposing some outrageous gaff or other, they’re still giving him vast amounts of time—much more than they’d give something like global warming.

And just remember: the role of money, media, and party strategies—everything that made Trump the Republican presidential candidate—is not going to change by behaving like viewer-consumer-voters, to those processes are likely to produce more outrageous versions of the same.

Living in Denial, Voting in Denial

Prof. Gregory was moved to offer his advice after watching “Bernie Sanders’ supporters struggling to come to terms with the nomination of Hillary Clinton.” This even presents it as though the problem were theirs… something that could be comforted by a fairy tale going back over eighty years of unacknowledged repression, betrayals and disappointment.

The economic implosions of 2008 changed everything, despite the official denials. The many who are actually experiencing life at the bottom of the social ladder—especially the young trying to enter more fully the economic life of the country—feel robbed of their futures.

A series of interrelated developments promulgated by both parties contribute to this unprecedented level of alienation, including:

- a consistent and conscious neglect of scientific evidence of global warming fueled by the human economy, particularly the reliance on fossil fuels and corporate farming

- a series of wars of unprecedented expense but unwinnable because they are waged against practices rather than enemy countries, such as “the war on drugs” and “the war on terror,” the latter waged in the direct interest of controlling the global supply of fossil fuels

- deliberate government lying justified these wars and the record profits for what President Eisenhower called “the Military-Industrial Complex”

- the persistent assertions by the government that it can constitutionally and legally exercise what used to be called the power of martial law at home, with the concomitant institutionalization of kidnapping, mass detention without habeus corpus, the use of torture, and assassination by mere executive order.

- the mass incarceration of particularly young black men, largely under the blanket authority of a “war on drugs,” an amorphous blank check for expanding unaccountable

- the vindictive prosecution of whistleblowers on government and corporate wrongdoing

- the systemic militarization of the police to the point where it often appears and functions like an army of occupation in our cities

- the contemptuous series of murders demonstrating that, while a black president provides a useful image, black lives in the streets really don’t matter.

- the wealthy, powerful and connected—from Wall Street to Pennsylvania Avenue—have been caught red-handed lying us into wars, violating national security standards, engaging in insider trading, and engaging in a range of other crimes and avoiding prosecution, indictment or even investigation when prosecutors claim problems demonstrating criminal intent.

Since bipartisan consensus places radical economic change beyond the reach of the voters, this problem can’t be addressed from within the two-party system, though they might paint a racing stripe on the inequality and invent something like “symmetrical universal prosperity.”

The Elephant (and the Donkey) in the Room

The fear is that the Sanders supporters—and others distrustful of Democratic promises of fair treatment—will do “something hasty” that might damage the America two party system. One can claim (dishonestly) that any multiparty system is a two-party system by just stopping the count at two. In terms of a winner-takes-all electoral system in which virtually everyone elected belongs to one or the other party, the U.S. shares its two-party system with only Jamaica and Malta. That is a system of representation for an island of three million in one case and under half a million in the other is assumed to be the best of all possible political system for a complex superpower with 325,000,000 radically diverse peoples spread across an entire continent.

Moreover, one of the two parties available on each of the islands—the People’s National Party in Jamaica and the Partit Laburista on Malta—represent social democratic formations with an actual ongoing membership base of citizens. In contrast, both U.S. parties are classic eighteenth century “caucus parties,” creatures of like-minded officeholders and any professional bodies they might employ to do their bidding. Any kind of citizen participation in the process is historically very recent and, as we’ve seen in the recent primaries, very limited and managed.

At its best, the two-party system persistently fails to encourage one side to be much better than the other. A little bit better would do fine, since the voters didn’t have any other options. What this means now is that the Democrats feel absolutely no pressure to have a serious policy discussion rooted in their candidate’s record.

It actively discourages voter turnout. Citizen participation is massively heavier in multi-party governments, where citizens are directly members of parties programmatically defined to do more than merely control the budget. Then, too, the history of the two-party system is riddled with efforts of one or the other to gain an advantage by excluding each other’s voters, reducing voter participation. A multi-party system has more eyes on what government does… which—come to think of it—might be why the present power structure is so opposed to it.

In my honest opinion, nothing could better come out of the Sanders campaign than a permanent, decisive break with the shell game. For many reasons this did not happen in the 1960s and 1970s, but it can happen now.

So, as the silly marathon continues, which one are you ready to start hallucinating as to who will be your Dudley Do-Right? Or are we ready to be adults about this and allow ourselves to think about historical processes and possibilities?

Good luck to us all.

[1] Loluis Proyect, “Tensions between Upton Sinclair and the Socialist Party,” https://louisproyect.org/2016/02/10/tensions-between-upton-sinclair-and-the-socialist-party/; and, Lance Selfa, “Upton Sinclair and the Democrats’ dirty tricks,” https://socialistworker.org/2016/04/25/upton-sinclair-and-the-democrats-betrayal

[2] The American Presidency Project “was established in 1999 as a collaboration between John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters at the University of California, Santa Barbara.” americanpresidency.org, Sources are: Peters. “General Election Campaign Financing.” The American Presidency Project. Ed. John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA: University of California. 1999-2012. Peters’ sources are: The Federal Election Commission. 1860-1996: Lyn Ragsdale, Vital Statistics on the Presidency (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Press, 1998), 146. The date had been posted on the www at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/data/financing.php.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.