A Century of Teacher Organizing: What Can We Learn?

By Adam Mertz

This article is part of the Teachers Initiative Project (Rosemary Feurer, Chair) for the Labor and Working Class History Association. Published October 2014 LAWCHA.org

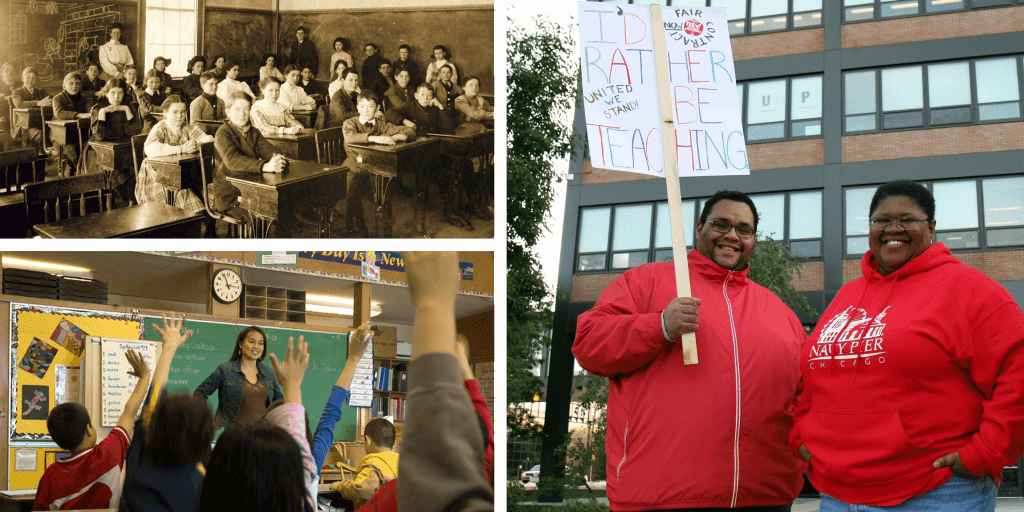

The history of teacher unionism is rich and vibrant, filled with numerous triumphs, tensions, and setbacks. For over a century, most education employees have been part of a public sector workforce that has been constrained by legal frameworks that assume that they are not entitled to the same rights as private sector workers. Because they comprise the largest segment of public sector labor, the story of why and how teachers sought to organize helps us understand many current debates surrounding education policies and the labor movement.

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the National Education Association (NEA) were founded by different constituencies and for different purposes. In 1857, teachers and other educational professionals founded the forerunner to the NEA. The members thought of their organization as a vehicle to professionalize teaching as a career, like law and medicine. The organization’s leaders endeavored to have the teaching occupation be more prestigious, make the entrance requirements more standardized, gain higher pay, and allow teachers to have more say over their teaching conditions, as opposed to leaving control to reformers, politicians, and various community members. As the number of administrators in education increased, men staffed the majority of these new positions and led the NEA. The NEA leadership believed that instead of emphasizing changes in classroom conditions, they should aim to influence legislation in education. Consequently, few actual classroom teachers joined the NEA in its early years.

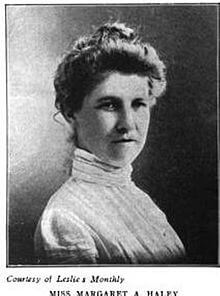

That changed near the turn of the century as classroom teachers, most of whom were women, pushed to have their voices heard within the organization and influence its policies and governance. Margaret Haley, a Chicago public school teacher and leader of the Chicago Teachers Federation (CTF), was one of the most important and inspirational figures in this effort. In her speech at the 1904 NEA convention, “Why Teachers Should Organize,” Haley spoke of teachers as workers. She proclaimed that in order for students to be free, democratic thinkers, their teachers must be as well. She concluded that teachers must, therefore, have better conditions in their classrooms and have their rights respected and their voices heard in the shaping of education policy. Ella Flagg Young, whom Haley’s allies elected as the NEA’s first female president in 1910, helped to transform the NEA. With Young’s and Haley’s leadership and continued support from classroom teachers, the NEA began to advocate for women’s equality, and in 1917 the association significantly reorganized its structure. Male administrators in state associations still dominated the association, but it paid more attention to improving the conditions of classroom teachers.1

While the NEA made some headway, many teachers who were interested in organizing remained skeptical of the NEA’s approach. This was especially true of many urban teachers who saw greater promise in collaborating with labor unions. Haley’s Chicago Teachers Federation was an innovator for this collaboration. Haley, along with fellow teacher Catharine Goggin, formed the union in 1897 and in 1902 affiliated with the Chicago Federation of Labor, the city’s affiliate of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). While the CTF remained the most influential teachers’ union local in the country, other urban teachers organized too. Working in the heyday of racial segregation and before women had many basic citizenship rights, the locals often divided into separate branches for men and women and, especially in the South, for blacks and whites.

In April 1916, some of Chicago teachers’ union locals joined with a few other locals to form the American Federation of Teachers, with Chicago as its first headquarters. Thereafter, for most of the twentieth century, the NEA and the AFT followed two different strategies. The NEA continued to seek to professionalize teaching through cooperation with education administrators and strong national and state-level organizations for lobbying legislators. The AFT, on the other hand, proudly called itself a union. It forbade administrators from joining and emphasized classroom teachers’ need for better pay and benefits. The AFT, being less interested in state and national education policy, “remained a loose federation of a few strong urban locals,” writes historian John F. Lyons. And while the AFT cooperated with organized labor, its leaders, like other public sector union leaders of the era, agreed not to engage in strikes.

Membership in both the AFT and NEA grew during World War I (1914-1918). Yet business and many elected officials still opposed unions in this era, and that limited the growth of the AFT. Owing to the Progressive Era emphasis on the “public good” and the “common interest,” the NEA fared much better because its leaders claimed the education administrators’ influence in the organization served to check teachers’ “excessive demands.” Those who opposed the AFT decried the union as a “special interest” that would harm the public at large. While many used this charge against all organized labor, it worked especially well against teachers, because they were paid through tax revenues and expected to serve the public and be loyal to their respective school districts. The era’s gender norms compounded this: women were expected to provide selfless care for others and to stay out of politics. Because most teachers were women, most other citizens viewed their participation in unions or demonstrations as inappropriate, since these were considered “manly” behaviors.

Hostility to unions surged immediately after World War I, when governments fell, territories changed hands, and revolutionary activity engulfed many countries around the world. A postwar “red scare” and open-shop drive rolled back many of the gains American unions had made in the private sector, while the 1919 police strike in Boston provided opponents of public sector unionism with a perfect case to support their argument that public employee organizing would lead to chaos. In the wake of that strike, many states, counties, and municipalities outlawed most types of public sector unions, including those of teachers. The AFT lost a significant number of locals, and its membership plummeted. The NEA, for its part, declared that teacher unions were unprofessional, distancing itself from the struggling AFT. Still administrator-dominated, despite its new “teacher councils,” the NEA continued to focus on improving education as a whole, rather than enhancing teachers’ compensation and conditions. In the new anti-union climate, its membership and influence grew dramatically.

The Great Depression of the 1930s brought renewed interest in teacher organizing and public education, yet the NEA and AFT responded differently because of the different traditions of their respective leaders and members. As the economic collapse depleted municipal coffers, many politicians and business and civic leaders pushed for and won drastic cuts in public school expenditures. Many teachers, in both urban and rural districts, saw their income plummet or lost their jobs altogether. In response, NEA leaders claimed that maintaining school funds benefitted all of American society, not just teachers. Shocked by what teachers were enduring, the AFT, in contrast, rallied around organizing them. Inspired by the dramatic growth in private sector unionization through the great strikes and militant unionism that spread after 1934, especially after the passage the Wagner Act in 1935, AFT activists saw an opening. Yet because the Wagner Act excluded public sector unions from protection and collective bargaining rights, the AFT made only temporary and tenuous gains that depended very much upon support from labor and labor-friendly politicians. And those gains varied radically by region and locality.

Like the wider labor movement of the era, the AFT was divided between those who wanted to remain with the more traditional craft-oriented AFL and those who favored the more militant, inclusive industrial unionism of the new Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Despite the challenges, however, AFT membership grew dramatically through the 1940s. In fact, against the wishes of the AFT national leadership, many AFT teachers participated in the massive waves of strikes that occurred across the United States after World War II as the wartime price controls expired and wages failed to keep pace. But because of the lack of legal protection for public sector unions and the growth of the second “red scare” as the Cold War set in, within a few years the AFT lost much of its militancy and some of its membership. As national politics shifted to the right in the Cold War era, the NEA’s continued emphasis on professionalism protected it from the kinds of attacks the AFT suffered.

Meanwhile, many female elementary teachers successfully persuaded their local districts to adopt equal pay scales: by 1951, 97 percent of school districts had pay scales that disregarded gender. The women teachers won over both the AFT and the NEA to the principle of reducing the gender gap in pay between male teachers (most of whom taught in high schools) and female teachers (most of whom taught in elementary schools). This was no small achievement because many urban male high school teachers opposed the change, seeking to maintain their higher pay and the prestige it afforded. Urban administrators also opposed the change because their districts saved money by paying female teachers less than male teachers.

From the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s, numerous developments in U.S. society encouraged public sector unionization—but also framed its boundaries. In 1955, the AFL and CIO merged, and the leadership of the newly combined organization used its collective resources to lobby for labor-friendly laws and to endorse and support pro-labor and pro-public sector politicians. Further, as collective bargaining in the private sector, in place for roughly twenty years, became relatively routine and stable, many private sector union workers enjoyed increased standards of living. Seeing the good that unions did, many Americans began to consider workers’ ability to join unions as a civil right. The general growth in government, especially the state and local levels, also made public employees’ rights a much more pressing issue. And the African American civil rights movement inspired many other oppressed groups to stand up for themselves, workers included.

In the more open political climate created by union and civil rights successes, most Americans became more willing to accept collective bargaining in the public sector, and they elected many labor-friendly politicians from both the Democratic and Republican Parties. While there was continual resistance from employers’ associations and the right, the pro-labor forces won out and passed laws that granted some collective bargaining rights to public sector employees.

In 1959, Wisconsin, long a laboratory of progressive public policy, became the first state to pass a collective bargaining law for its public employees when Democratic Governor Gaylord Nelson signed the bill into law. The bill passed largely thanks to significant lobbying from the state’s American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). While it was a significant step forward, the bill explicitly prohibited public sector strikes. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order 10988, which granted many federal employees limited collective bargaining rights. Despite significant lobbying from the AFL-CIO, organized labor failed to win all the legal rights it desired. The Civil Service Commission held the authority to interpret and enforce the law, making collective bargaining rights subject to the different ideologies of various presidential administrations and to new circumstances. Also, as in the Wisconsin law, federal public sector employees were forbidden from striking. Following the examples of Wisconsin and the federal government, twenty-two other states passed public sector collective bargaining laws by 1970. While these laws helped public sector unions secure immense gains, public sector workers never won the same rights as the 1935 Wagner Act had granted private sector unions. The laws also varied widely from state to state with few federal guarantees, which enabled right-to-work states, particularly common in the South, to deny collective bargaining rights. Further, these advances required alliances with labor-friendly elected officials, usually Democrats, a resource that grew rarer after the mid-1970s. Despite the limitations, public employee unions seized the significant opening and surged forward with unionization drives, with teachers often in the vanguard.

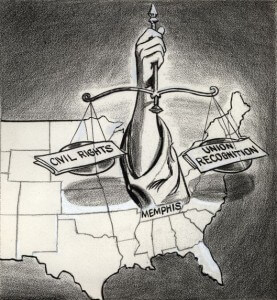

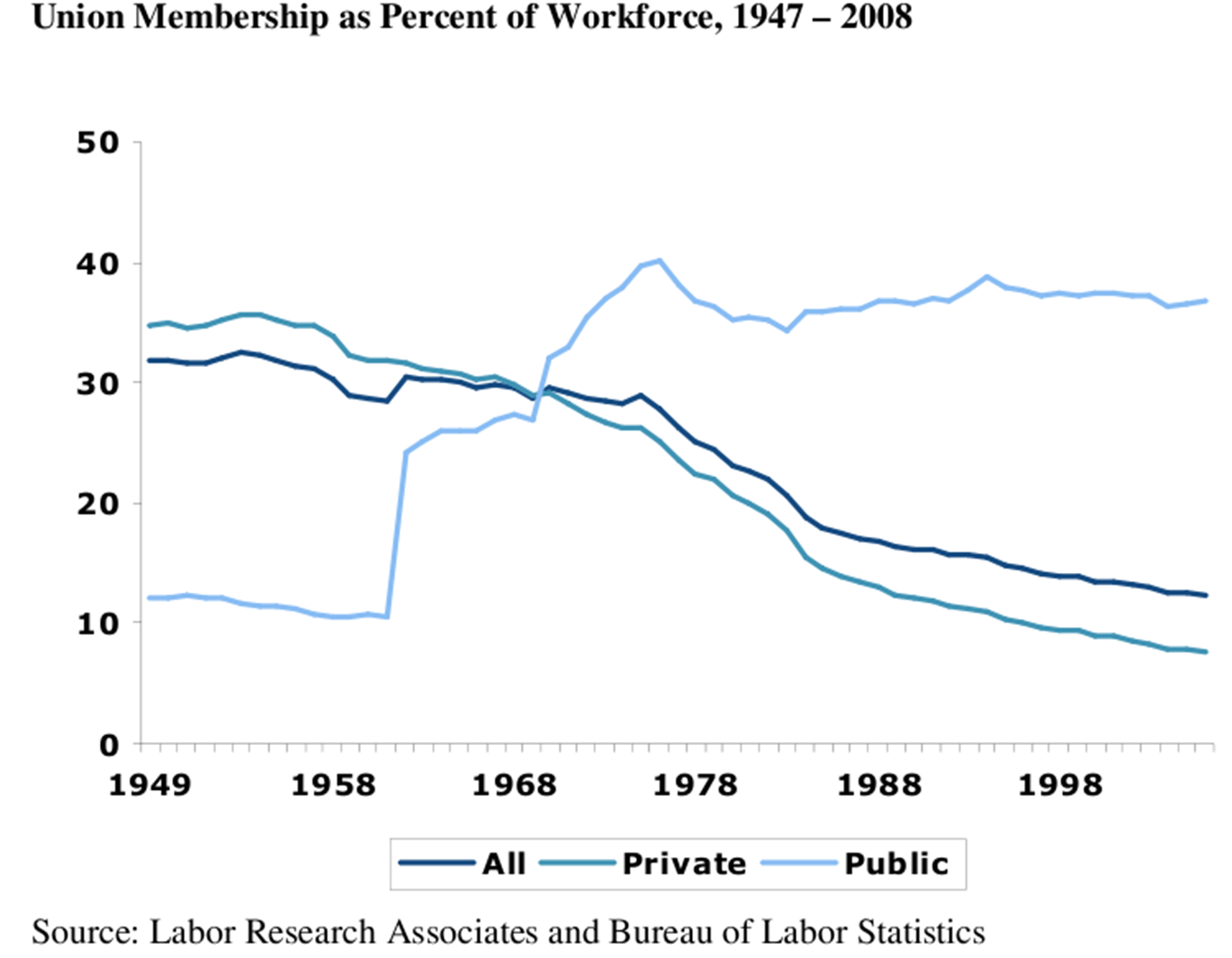

Public sector employees’ unionization efforts overlapped with the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, and the wider democratization of the era. Public sector employee activists claimed the right to unionize as a basic civil right. Many further argued that collective bargaining rights should flow naturally from the right to organize. By denying such rights to public sector workers, states were forcing them into second-class citizenship, unionists and their allies maintained. A prime example of the common cause made between civil rights and public employee organizing is the support the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave to the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike in 1968. Thereafter, organizing among African American public sector workers surged, including health care workers, teachers, and more. Their example emboldened others. As a result, says historian Joseph A. McCartin, “public sector union membership jumped tenfold between the mid-1950s and the mid-1970s. This surge was the biggest breakthrough for labor since the New Deal” of the 1930s.2

Teachers were often in the vanguard of this growth in public sector unionism. AFT activists in New York City spearheaded the movement. In 1960, AFT leaders Albert Shanker and David Selden unified many New York City AFT locals into the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) and organized a large, successful strike that won them collective bargaining rights in the New York City school district by 1963. Due to their affiliation with the AFL-CIO, Shanker, Selden, and other UFT leaders drew inspiration from the strikes of their private sector unionist brothers and sisters in the labor upsurge of the 1930s and 1940s. UFT leaders believed that since private sector workers had won favorable legislation through the use of strikes, dedicated teachers could too. The numerous examples of direct action by civil rights activists also inspired UFT leaders. Because striking to organize proved such a successful tactic, the AFT abandoned its no-strike pledge the same year. Emboldened by the New Yorkers’ example, many other teachers around the United States turned to strikes and collective bargaining to advance their cause, and the AFT grew in membership and in prestige. The AFT’s support for the Brown v. Board of Education decision (1954) and its opposition to racially segregated locals helped drive this momentum. In fact, the AFT’s new militancy proved so successful that the NEA took notice.

Out of both a genuine change in beliefs and pragmatic concerns to remain competitive with the AFT, the NEA changed its stances on both civil rights and teacher unionism. “In 1964,” explains historian Karen Leroux, the NEA’s “Representative Assembly voted to mandate desegregation within its affiliates and merge with…the all-black American Teachers’ Association.”3 The NEA gained further credibility on civil rights as a result of the UFT’s Ocean Hill-Brownsville strike in 1968, which pitted the union, an AFT affiliate, against African American advocates of community control of the schools. The NEA had enrolled many women and rural teachers, but now NEA leaders began to court the urban teachers in the forefront of the struggle. To do this effectively, the NEA adopted some aspects of unionism—albeit with hesitation and a continued emphasis on professionalism. Instead of immediately using the term “collective bargaining,” for example, NEA leaders used the term “professional negotiations.” Whatever banner it went under, the trend to unionization was underway. By 1973, the NEA made a decisive move: it finally expelled administrators from its ranks and significantly changed its constitution to enable it to operate like a union. While the NEA still refused to affiliate with the AFL-CIO, it now joined coalitions with other public sector unions and even waged many of its own strikes. The NEA also became known for its advocacy of racial and gender equality and success as a lobbying force for progressive legislation more generally.

Teacher militancy surged in these years. “Between July 1960 and June 1974,” says historian John F. Lyons, “the country experienced over 1,000 teacher strikes involving more than 823,000 teachers.” The strikes proved so successful for both the NEA and the AFT that by “the end of the 1970s, collective-bargaining agreements covered 72% of public schoolteachers.”4 Indeed, as both organizations’ memberships grew dramatically, their competition made them more like one another. Where the NEA became a full-fledged union, the AFT moved its national headquarters to Washington, D.C. in 1967 to better lobby the federal government. Both began making political endorsements in the early 1970s. In fact, they entertained the prospect of merging twice—in the early 1970s and in 1998. Even as they remained apart and in competition, their traditions merged: the AFT’s motto now is “A union of professionals,” while the NEA trumpets its “New Unionism.”

The very success of the teacher unions and public sector unions in general—as advocates both for their own members and for progressive public policies more generally—drew the attention and enmity of the political right and powerful business interests. Conservatives and free-market libertarians had expressed hostility to teacher unions and public education as early as the 1950s. In 1955, for example, Milton Friedman issued his call for school vouchers to promote private education with tax dollars. Thereafter, many zealous advocates of free-market policies targeted teachers’ unions, in particular, as obstacles to privatization, tax and benefit reduction, and balanced budgets.

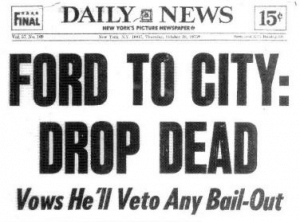

Some unfortunate timing in union demands in the mid-1970s further invigorated the opposition. Public sector unionists tried to achieve federal recognition of their right to collectively bargain, rights their private sector counterparts secured in 1935, and they came remarkably close to success. Yet a convergence of economic crisis and political challenges defeated the effort. Already in the early 1970s, the U.S. economy began to slow down and experience serious disruptions, largely as a result of expanding global competition and the worst recession since the 1930s. In reaction, public officials drastically reduced government budgets at all levels, but especially state and municipal governments, which led to reductions in expenditures. New York City’s 1975 financial crisis is the most famous example.

Inflation hurt all workers, including public sector workers. When public sector workers went on strike to keep their pay at or above inflation rates, their opponents seized the opportunity to portray public sector workers as greedy and privileged at the expense of the general public. Indeed, public sector labor’s activism, which elevated a significant number of African Americans and women, helped fuel the growing conservative movement of the 1970s and the wider corporate mobilization that funded it. Squeezed by stagflation, agitated by conservative spokesmen, and leery themselves of growing public sector union power, many politicians and some of the general public directed hostility toward striking teachers even as state legislation friendly to teachers’ unions remained on the books.

Despite the mounting opposition, the vast majority of public sector unions across the country continued to wage strikes, often militant ones, throughout the 1970s and into the early 1980s. Their tactics changed quite abruptly, however, in the aftermath of the 1981 PATCO strike, when President Ronald Reagan fired all of the over 10,000 striking air traffic controllers. This very public, drastic action encouraged public sector unions’ opponents. “In the fall of 1981,” explains historian Joseph A. McCartin, “teachers, the leading edge of government employee unionism in the 1970s, complained that school boards were demanding an unprecedented number of concessions in contract talks.” In the long-term, the conclusion of the PATCO strike also compelled public sector workers to rethink striking as a tactic, especially because of the support Reagan received for his actions. Facing such opposition, teacher unions—and public sector unions in general—shifted their efforts away from strikes and toward endorsing political candidates and lobbying government to pass favorable legislation. Public sector union leaders also accepted this new strategy because they felt they had largely realized their original goals of gaining collective bargaining rights. So while public sector unions “survived the post-PATCO-strike era and remained the most vibrant part of the labor movement in the late twentieth century,” McCartin concludes, their overall rate of membership growth leveled off and they became “much less willing to strike.” Given these constraints, public sector unions enjoyed a large degree of success in the 1980s with this new political unionism, as some called it, even as private sector union membership plunged to less than ten percent of the workforce. This trend continued throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, when opponents mounted few major, successful attacks against public sector unionism.5

But when the Great Recession began in 2008, public sector workers became the targets of new austerity policies when their opponents claimed, once again, that public sector workers represented a privileged class, enjoying greater rights and benefits than private sector workers. The most vicious opposition to public sector unions came from Tea Party-backed politicians and their supporters, who took advantage of the economic crisis to push for policies the political right had sought for decades. Most famously, Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker pushed through a bill to strip public sector workers of collective bargaining rights, setting off one of the most pitched battles of the recent era, the “Wisconsin Uprising.” But liberal supporters of “school choice” also argued—and increasingly took action—against teacher unions and public education, from the Democratic Obama administration to the mayors of many once union-friendly cities.

[/caption]

While public sector workers suffered some enormous setbacks in several states, they did not surrender. Teachers, teaching assistants, firefighters, and other public sector workers organized massive protests in Wisconsin in 2011 that drew national sympathy. Their fight, in turn, helped give rise to the Occupy Wall Street movement. As residents of cities and towns across the country launched their own Occupy protests, a searching national discussion opened about what surging inequality means not just for the public sector but also for democracy.

The following year, after long internal and community organizing, the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) went on strike—its first since 1987—to protest what its members depicted as a corporate-backed effort to undermine public education. The vast sympathy the teachers won from their students’ parents, two-thirds of whom backed the strike, provided a model for the nation of labor-community solidarity in defense of public goods. Indeed, Becky Malone, a member of the 19th Ward Parents organization and a parent of two students in Chicago Public Schools, combined the concerns of teachers and the community into a unifying defense of the CTU: “As parents we support our teachers, because…our teachers’ working conditions are our children’s learning conditions.” Teachers, Malone continued, “are looking out for the best interests of our children, and for that they deserve the support from us as parents and community members.”6 The CTU’s success in building solidarity has inspired education unions in other cities to reach out to parents and potential community allies on a scale not seen for a decade.

Teachers today feel under siege from both traditional union opponents and from education “reformers” who attack teachers’ unions and tenure and impose high-stakes testing on teachers and students, all of which undermine teachers’ professional prerogatives and dignity—not to mention the negative effects on students. In order to defend their rights, teachers beyond Chicago are increasingly seeking out community coalitions and alliances with other labor unions. In a sense, then, teachers’ unions seem to be returning to their roots: to the kind of broad-based community engagement Margaret Haley and Catherine Goggin practiced over a hundred years ago when they founded the nation’s first teachers’ union.

Further Reading

For a better understanding of public sector unionism in general, see Joseph A. McCartin’s interview on “History for the Future” , Melissa Maynard “Public Strikes Explained: Why There Aren’t More of Them.” Stateline. September 25, 2012., and Joseph E. Slater, “Public-Sector Unionism,” in the Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class History. For more information about how public sector unionism is taught in history textbooks, see Robert Shaffer, “Where Are the Organized Public Employees? The Absence of Public Employee Unionism from U.S. History Textbooks, and Why It Matters,” in Labor History, Vol. 43, issue 3 (2002), pp. 315-334.

For a concise history of the NEA, see Karen Leroux’s essay, “National Education Association,” in the Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class History.

For more on Margaret Haley and her organizing efforts, see Kate Rousmaniere’s book Citizen Teacher: The Life and Leadership of Margaret Haley.

For more on women in the NEA, see Wayne J. Urban “Courting the Woman Teacher: The National Education Association, 1917-1970.” History of Education Quarterly Vol. 41 No. 2 and Wayne J. Urban, Gender, Race, and the National Education Association: Professionalism and Its Limitations; for more on the NEA’s work and successes, particularly in the areas of racial equity and funding for poorer school districts, such as the landmark Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, see Allen M. West, The National Education Association: The Power Base for Education.

For teacher union involvement in the other movements of the 1960s and 1970s, see Marjorie Murphy’s essay, “Militancy in Many Forms: Teacher Strikes and Urban Insurrection, 1967-1974,” in Rebel Rank and File: Labor Militancy and Revolt from Below in the Long 1970s.

For more information on the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Strike, see Jerald E. Podair’s book The Strike That Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis.

For an excellent comparison of the evolution of the AFT and NEA, see Marjorie Murphy, Blackboard Unions: The AFT and the NEA, 1900-1980.

For the reaction of teachers unions and public sector workers to the 1975 financial crisis, see Jon Shelton “Against the Public: The Pittsburgh Teachers Strike of 1975-1976 and the Crisis of the Labor-Liberal Coalition.” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 10:2 (Summer 2013), Joseph A. McCartin “‘A Wagner Act for Public Employees’: Labor’s Deferred Dream and the Rise of Conservatism, 1970-1976.” Journal of American History 95:1 (June 2008), Joseph A. McCartin, “‘Fire the Hell out of Them’: Sanitation Workers’ Struggles and the Normalization of the Striker Replacement Strategy in the 1970s,” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 2:3 (March 2005), and Joseph A. McCartin’s interview on “History for the Future,” called “Public Sector Unions and Worker Rights in Wisconsin.”

For an illuminating account of the 1981 PATCO strike and the long effort to organize these public workers, see Joseph A. McCartin, Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, the Air Traffic Controllers, and the Strike that Changed America.

For the 2011 protests in Wisconsin and their broader import, see Peter Rachleff “‘Rebellion to Tyrants, Democracy for Workers’: The Madison Uprising, Collective Bargaining, and the Future of the Labor Movement.” The South Atlantic Quarterly Vol. 111, No. 1 (Winter 2012); for the effects of Governor Walker’s policies, see Steven Greenhouse, “Wisconsin’s Legacy for Unions,” in The New York Times, February 22, 2014.

For more on the 2012 Chicago Teachers Union Strikes, see Tom Alter “‘It Felt Like Community’: Social Movement Unionism and the Chicago Teachers Union Strike of 2012.” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 10:3 (Fall 2013).

For other examples of collaboration between teachers’ unions and community members, see Rachleff, Peter. “The Present, Past, and Future of Collective Bargaining.” Twin Cities Daily Planet, March 19, 2014. and the Belabored podcast, Episode 42: “(Almost) Striking in Portland,” February 22, 2014.

Footnotes

1. Chara Haeussler Bohan, ed. Readings in American Educational Thought: From Puritanism to Progressivism. (Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing, 2004), 387-388.

2. Joseph A. McCartin, Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, the Air Traffic Controllers, and the Strike that Changed America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 43.

3. Karen Leroux, “National Education Association,” in Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class History, ed. Eric Arnesen (New York: Routledge, 2007), 955.

4. John F. Lyons, “American Federation of Teachers,” in Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class History, ed. Eric Arnesen (New York: Routledge, 2007), 89.

5. McCartin, Collision Course, 341.

6. Ellyn Fortino, “Parents, Teachers Rally For Fair Contract, Better School Conditions At Board of Ed Meeting,” Progress Illinois, 27 June, 2012.