Reflections about the importance of workers power in American aspirations seem particularly appropriate at the approach of this President’s Day–that holiday formed by the compressed birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and George Washington. In my life, I cannot recall when they’ve ritually chanted their rhetoric about opportunities in circumstances as dire as these for working people. Faculty at many universities face a management that has looked more like Walmart’s every year, cynically fostering such a deep desperation in the work force that it will allow the robbery of its most elementary and hard-won benefits and protections. Meanwhile, the current president sneers at the value of studying art history, adding his preference for “practical” disciplines aimed at making an easier world for the ever-mythical “job creators.”

We are also in the midst of the 150th anniversary of the great national crisis in which ideas of “free labor” transformed the work force in the United States and, for many, the nature of those American aspirations themselves. On the eve of that war, Abraham Lincoln visited his son at college in New England and was asked about the shoe strike that had swept 17,000 workers, including several thousand women into what was, to that date, the largest work stoppage labor had held. Some of the Democratic politicians had been trying to cozy up to those workers, arguing that the reason they had to strike was that the market for their employers to sell shoes in the south had shrunk owing to fear of antislavery sentiments in the North. Asked his view of the strike, Lincoln replied, “I am glad to know that there is a system of labor where the laborer can strike if he wants to!” He added, “I would to God that such a system prevailed all over the world.”[1]

Aimed as it clearly was at the slaveholding system, it is hard to interpret Lincoln’s pointed assertion of this right, as something he wished to prevail only for white men in the North. One just can’t find a Democrat or Whig of prominence saying that workers should be have a right to strike . . . no ifs, ands or buts. Reasonably, his insurgent views made him one of the new Republicans, not that the shared label means any similarity of his vision with those who currently flaunt either that label or that of the Democrats first adopted to protect the slaveocracy.

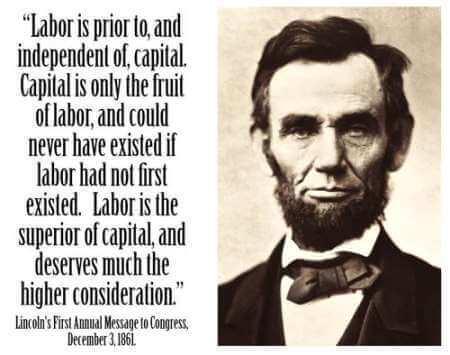

While Lincoln’s course was certainly never above criticism, it proved to be fairly consistent in discussing this aspect of “free labor.” The Federal military sometimes broke strikesduring the war, a common practice in modern wars by the most reputedly “pro-labor” presidents. But, during the Civil War, strikers and other workers with grievances found a sympathetic ear in the White House and a willingness to use what Lincoln saw as thelimited power of his office to allow for a fair contest in disputes between labor and management, one in which “the best blood would win.”[2] And when wartime black labor easily rolled over the shoemakers record by waging the largest strike in U.S. history, Lincoln ultimately threw the weight of government behind it. And “the best blood” won emancipation.

Whenever I hear Theodore Roosevelt or Woodrow Wilson or Franklin D. Roosevelt or any other Chief Executive described as “pro-labor” I can’t help but think of these great transforming experiences under Lincoln and their importance in shaping the aspirations of American workers. What does it mean to wish “to God that such a system prevailed all over the world” in a nation that seizes and wields an imperial power to promote the dictatorships of owning institutions abroad against the rights of free labor in country after country.

What can any of this mean where we permit public office to go to those who are simply the most well-financed? Where corporations are people and government simply regards their unlimited dollars spent to buy office as free speech, while money and markets bury the concerns of flesh-and-blood people. Where an unblinkingly media reports the Justice Department position that no citizen has any rights that government, in its “war on terror,” is actually required to respect. Who hears this without remembering the Dred Scott decision that no black person in America has any rights a white man is legally bound to respect? “If destruction be our lot,” warned Lincoln, “we must ourselves be its author and finisher.”

Conversely, one cannot but wonder how the debate over slavery might have gone had it been simply a one-sided 24/7 propaganda barrage where the patriotic apologists for the status quo had been denouncing any changes that might cost the “job creators” and “wealth generators” money and power.

In the Gilded Age that came out of the Civil War, the promise faded of reshaping the nation in the interest of free labor. Today, we hear bosses, media and politicians wanting more power to remake people to suit the needs of government and the marketplace. In this second Gilded Age, labor activists and historians should recall the aspirations that it should actually be the people who shape the institutions to their needs, and that, without struggle, this never happens. And that history does provide examples where large numbers of insistent people have done just that.

[1] March 5, 1860 statement, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed., Roy P. Basler 9 vols. (New Brunswick NJ, 1953-55), 4: 7.

[2] “The Strikes. Mr. Lincoln on the Strikes,” New York Daily Times, December 5, 1863, p. 6.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.