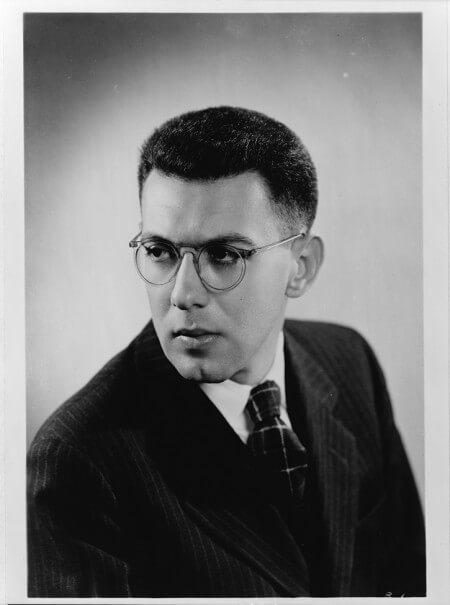

Was Herbert Hill–the Labor Secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for 25 years known for his fierce criticism of labor union racism, and longtime labor and civil rights movement historian at University of Wisconsin–an “FBI informer”?

Yes, but.

Yes: University of Nottingham professor Christopher Phelps has convincingly drawn together scattered documents to prove that Hill, who left the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in 1949, provided information to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) about his former SWP comrades between 1953 and 1955. Phelps released his findings in an article, “Herbert Hill and the Federal Bureau of Investigation,” which Labor History [ed: this was changed after C. Phelps comment below] published online on Thanksgiving Day, 2012. The publication was accompanied by a University of Nottingham press release and youtube video, and circulated by Phelps himself in a mass email to labor historians subscribed to the H-Labor list serv.

But: recently released documents from the FBI’s New York City field office on Herbert Hill, which do not appear to have been available to Phelps and which are published online here for the first time, suggest that Hill was not the kind of figure that people in the general public often associate with the term “informer” or “informant.” Whereas Richard Aoki and Ernest Withers were recently outed as paid FBI informants, and contentious debates followed over their having lied to their friends and family, the information contained in FBI files about Herbert Hill is much less explosive. There is no evidence in documents released so far that Hill infiltrated any organization on behalf of the FBI in order to secretly report on it or to disrupt its activities. And the people Hill named to the FBI were part of an organization that he publicly and contentiously broke from five years prior, making the disclosure of his relationship to the FBI seem less out of character, even if it remains problematic.

The New York file on Herbert Hill indicates that he did not approach the FBI of his own accord, but was approached by them for information about the SWP. Worried that the FBI would compel the NAACP to fire him (and leave him blacklisted) because of his prior history with the SWP, Hill identified previous SWP members to the FBI, even going so far as to try to identify people who used pseudonyms to protect their identities. Whether Hill’s public break with the SWP and possible personal animus toward specific individuals played a role in Hill’s collaboration with the FBI is unclear. But it is clear that Hill did more than name names. He also shared information with the FBI about his work to prevent communists and socialists (including former SWP allies) from attending or participating in NAACP meetings. The file does not contain evidence that the FBI assisted Hill or others in the NAACP with the enforcement of its anticommunist membership policy.

Read a different way, the FBI’s files on Herbert Hill reveal as much about the FBI as they do about Hill himself. Hill may have been wrong to believe that he faced a stark choice between informing on his former allies and being blacklisted himself. But regardless of the personal decision that he made, it is also important to note that the FBI seems to have cultivated or at least capitalized upon Hill’s anxiety about his vulnerability to red-baiting for its own ends. Under the pretense of investigating the SWP, the FBI quietly exerted extra-legal and sometimes anonymous pressure on Hill to prove his anticommunist credentials: to expel leftists from the NAACP, and to prevent the NAACP from allying itself with leftists in the civil rights movement. In this regard, the FBI file on Herbert Hill is not just about how or why Hill felt compelled to cooperate with the FBI’s campaign against the SWP. It is also about how the FBI sought to use fear of the blacklist to drive a lasting wedge between liberals and the left.

An Archival Fragment

The FBI file that accompanies this story is not just redacted. It is also a mere fragment of the FBI’s entire archive on Hill.

I acquired the FBI’s Headquarters file on Herbert Hill in October, 2009. The paltry 24 page release inspired me to follow up with another request, which the FBI responded to in March of 2010 by releasing a 338 page file on Hill from the New York City field office file. Only after Phelps published his findings did I give the New York file a close enough reading to realize that it contained evidence that Hill identified former SWP comrades to the FBI. That Phelps wrote his article over two years later without citing these documents indicates that either he did not request them from the FBI, or that the FBI did not disclose their existence to Phelps as they should have.

New York was hardly the only FBI field office that had a file on Herbert Hill. The Seattle FBI field office, for instance, maintained a file on plans by Seattle activists to bring Herbert Hill to speak about labor union racism in 1967. That 55 page file—more about the event than about Hill himself— does not appear to have ever been shared with FBI Headquarters, because it grew out of a local rather than national investigation.

Dozens of other field offices likely had files on Hill similar to the Seattle file, but the FBI claims it can’t locate them. The FBI acknowledged destroying files with information on Hill from its St. Louis and Denver field offices. In addition, even though the New York City file clearly indicates that multiple cities kept files on Hill (including Detroit, Albany, and Chicago), the FBI claimed to be unable to locate any files on Hill in its “Albany, Baltimore, Boston, Buffalo, Chicago, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Detroit, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, New Haven, Newark, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, and Washington [DC] Field Offices.” If any files were transferred to the National Archives, they are not listed in NARA’s Archival Research Catalog.

Finally, though Hill is referenced in COINTELPRO-SWP documents, copies of those documents do not show up in the files that the FBI has released to the public in response to FOIA requests about Hill. This suggests that documents may have been removed from files that have been released, or that the scope of unacknowledged files on Hill may go beyond just field office files.

Ed: See this link for Trevor Griffey’s analysis of Hill’s FBI file, or view it below.

Response from Christopher Phelps

Christopher Phelps posted the following response to Trevor Griffey’s analysis on Saturday, January 26, 2013. It is posted here so it does not fall below responses.

I am grateful to Labor Online for giving attention to my article “Herbert Hill and the Federal Bureau of Investigation,” and I salute Trevor Griffey for releasing additional FBI files not available to me at the time I wrote my article.

This new evidence is further proof for the validity of my conclusion that Hill supplied the FBI with information on his former comrades in the Socialist Workers Party, to which he belonged for most of the 1940s. Virtually everyone who contacted me about my article when it came out found the evidence I provided conclusive, but a handful of Hill’s friends did resist. These additional findings, I think, close the casebook completely.

I have not yet had time to read through all 300-plus pages of this new additional FBI file to reach my own conclusions about what it contains, and of course wish it had been available to me before, but based upon Griffey’s post above and his linked PDF, here are some reactions.

First, my article, “Herbert Hill and the Federal Bureau of Investigation,” was published in Labor History, not Labor, in case that should introduce any confusion. (This blog is associated with Labor, which did not publish the original article of mine but did after Hill’s death publish a set of very interesting reflections on Hill by Nelson Lichtenstein, Nancy Maclean, Alex Lichtenstein, and others, all cited in my article. Both journals are valuable.)

Second, here is what I think is genuinely new in these additional FBI files obtained by Griffey:

- That 1953 was the first date of Hill’s cooperation with the FBI. (The files I had alluded to past cooperation but were all from 1962, making the initial date indeterminant; I had hazarded a guess of about 1950, based upon a mention of Hill in a Communist publication at that time, which I thought would have tipped off the FBI to him, but this pins it down.)

- That Felix Morrow, an intellectual who had been in the SWP, was the one who pointed the FBI to Hill as a possible source.

- That one of the SWP names Hill named to the FBI was George Weissman.

- That at the 1955 NAACP convention in Atlantic City, Hill acted to eliminate SWP members from the ranks of the NAACP delegates.

- That according to the FBI, SWP members interpreted Hill as friendly to him even while he was in this way acting against them.

Third, Griffey implies that some other things are new about his findings which I do not believe are actually new: That Hill did not infiltrate the SWP for the FBI, that he did not attempt to disrupt the SWP from within it, that he had broken with the SWP before sharing information with the FBI, and that he did not approach the FBI but was approached by them. All of these are consistent with my original findings. Because the words “Yes, but” and “But” appear before these in Griffey’s post, I am concerned that his words may be taken to be a correction to my article rather than a corroboration of all these aspects. But these points are perfectly consistent with the way I interpreted Hill’s role. I never said he infiltrated or disrupted the SWP, I said explicitly that he broke with the SWP before sharing information with the FBI, and I said the FBI approached him rather than the other way around. I called him an “informant” rather than an “informer” (despite the quotation of “FBI informer” by Griffey in his first sentence, implying I’d used those words), since I see the latter word as more laced with associations with agents, plants, and provocateurs, none of which did I claim Hill had been. (I also made this distinction explicitly in the video the university here circulated about my findings.) Griffey is drawing our attention properly to the need to make fine distinctions in the way we understand the way the FBI has made use of different actors and sources.

Finally, I regret that Griffey’s post on these new FBI files suggests, in reference to me, that “he did not request them from the FBI, or that the FBI did not disclose their existence to Phelps as they should have.” Griffey contacted me a few days before publishing his blog post, and asked me if I had requested the FBI files on Hill and when. I informed him that I had put in an FOIA request for all files related to Hill on February 1, 2012, but that the response I received indicated that the process was going to take a long time so I gave the green light for publication of my article, persuaded that my already found evidence, based on the COINTELPRO file on the SWP, was sufficient to make the claims I did. The FBI has told me the Hill files exist but have been sent to NARA; NARA sent me a letter a week ago stating that in four months I will get them. This too I told Griffey. Why then make the suggestion that I had not requested them? As for whether I should have had them sooner, I agree, but that’s bureaucracy. I am not unhappy that Griffey beat me in the Great Document Hunt, but I find it needless for him to have suggested that I wasn’t hunting too.

What Griffey’s FBI research provides is important new evidence. The case is now closed on Hill’s having informed on his ex-comrades in the SWP. The questions we are now left with are ones of significance, effect, and meaning. Thanks to Labor Online and Griffey for the very welcome new information.

4 Comments

Comments are closed.