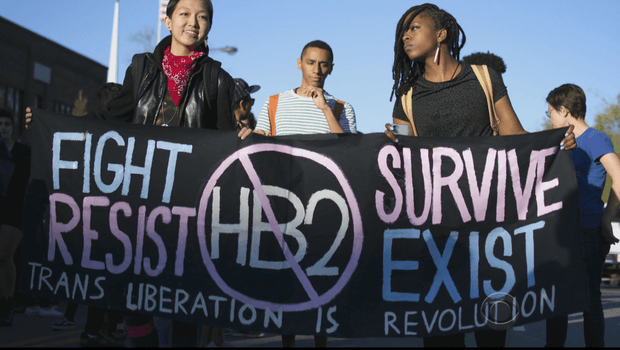

HB2, a North Carolina provision that limits bathroom access for transgender people, has sparked a new conversation about the laws that protect us at work. Many of HB2’s opponents have pinned their hopes on Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the once-ambiguous federal provision that now shields workers from gender stereotyping and sexualized attention. They have urged courts to use Title VII to grant transgender workers the right to use the bathroom that matches their gender identity.

But Title VII has been an unreliable route to gender-based justice for women and sexual minorities. As government officials have boosted workers’ right to be treated as sex-less individuals, they have also extinguished broader sex-based claims and narrowed our notions of equality.

Even before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the agency created to interpret Title VII, was up and running, women sent commissioners free-form letters outlining their personal expectations of their new rights. Many of these women demanded changes to their jobs that would enhance their autonomy and economic security: flexible leave policies, clean restrooms, protections against capricious bosses, and wages high enough to meet their financial needs. The EEOC’s lack of concrete policies or definitions of sex equality allowed some within the agency to pursue these claims on workers’ own terms. But by the early 1970s, EEOC officials increasingly defined sex equality as something they could use statistics to measure. Bureaucrats began to treat sex discrimination more as a phenomenon they could see for themselves and less as an issue of women’s own expectations and experiences.

In the decades that followed, workers and activists continued to test Title VII’s meaning by advancing broad interpretations of sex equality. The National Organization for Women sought to leverage Title VII to end many of the abusive practices that span today’s service sector: reclassifying full-time workers as part-time to deny them benefits, rigid and just-in-time scheduling, and poverty wages. Gay and lesbian workers attempted to win Title VII protections against sexual orientation discrimination. They argued that sexuality, like sex, was an immutable identity that workers should not have to downplay or deny. Other activists attempted to use Title VII to transform pay practices nationwide. Comparable worth advocates argued that the sex equality promised by Title VII required employers to recalculate wages free from sexist values—according to the value a worker created. Courts blocked each of these efforts to expand Title VII’s promise to workers.

The conception of workplace rights as belonging to individuals rather than serving as a bulwark against sexist systems has become so entrenched that the 1.5 million women who sued Walmart over its discriminatory employment practices never even had their Title VII claim heard on its merits. These women accused the corporation of perpetuating institutional sexism through lower pay, stunted promotion opportunities, and abusive workplace culture. In 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court expressed its interpretation of sexism as an interpersonal rather than a systemic problem. Justice Antonin Scalia wrote that the women’s voluminous evidence did not include adequate “glue holding…together” the “literally millions of employment decisions” they experienced one by one.

As the Walmart case demonstrates, employers have weathered the civil rights revolution by accepting a definition of equality that does not require them to do much beyond treat workers interchangeably. This framework has made it harder for workers to gain substantive protections or accommodations for their responsibilities outside of work. For example, the Supreme Court has protected women’s right to work in jobs that expose them to chemicals that cause fetal health defects rather than imposing stricter safety standards, and the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 grants only some workers up to twelve weeks of unpaid leave. The narrow definition of sex equality that Title VII now protects has helped a relative handful of women to break the glass ceiling while employers lowered the floor for everyone else.

HB2 should be struck down. All workers should have the right to use the restroom that aligns with their gender identity. But we should also fight to strengthen transgender workers’ rights where they diverge from other workers’ and require employer accommodation—for example, health benefits for transition-related care and longer and more flexible medical leaves.

We should use this moment to have a more substantive conversation about the nature of the equality all Americans deserve and the government’s role in delivering it. The right to equality does not mean much if it is bound up in an employer-driven race to the bottom that renders all workers interchangeably vulnerable.