As the president of the US announces new historical monuments, ranging from Harriet Tubman to 240,000 acres of land in New Mexico, it is a moment for each of us to remember how workers history is ignored and how we need to stop being academics and become organizers to promote it. Because “those who control the past control the future,” as George Orwell stated, it is no surprise that the determination by the 1% to eliminate unionism in the United States includes scrubbing history of any positive description of the labor movement. Denied our own labor TV shows in prime time, we each do what we can. One small movement was the unveiling on March 23 in downtown Baltimore of a Maryland State Historical Marker honoring the railroad strikers of 1877.

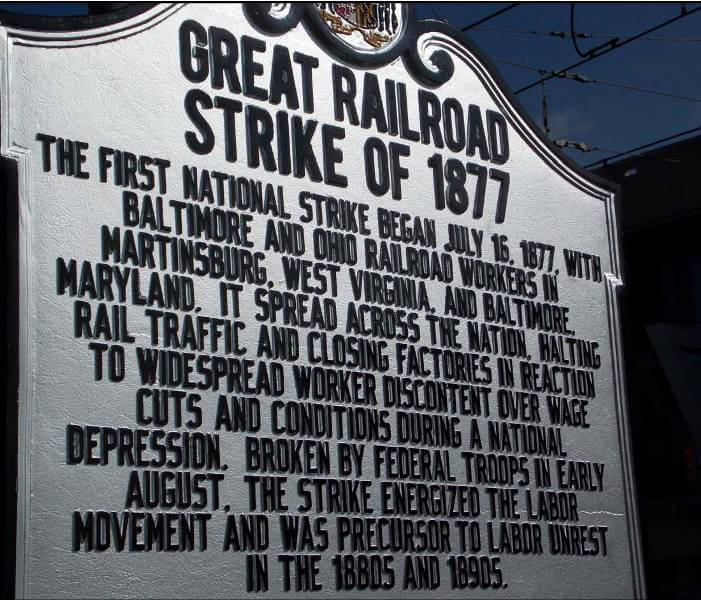

The marker was placed at Camden Yards—now the city’s heavily-subsidized baseball stadium—because it was the site of the first group of brakemen and firemen who refused, on the morning of July 16, 1877, to accept the second round of 10% pay cuts forced by John Garrett, president of the B & O. The strike spread down the B & O lines to Martinsburg, WVA, and then to other cities and other railroads across the US and Canada. Within days, tens of thousands of workers, their families and communities were involved in an epic struggle, not just against the railroad bosses but against local, state and federal governments, who brought in military forces—local police, state militia and federal troops—to break the strike. And yet most of the citizens of Baltimore know nothing about the strike, deluged as we are this year with the War of 1812.

Getting the marker erected (and paid for by the taxpayers of Maryland) was surprisingly easy. I submitted a proposal last year, honestly despairing that it would ever be seriously considered. There are only two other historical markers about workers in Maryland: a monument to Mother Jones—memorialized as “Grand Old Champion of Labor”–at her last house in Adelphi, and a marker commemorating the Latimer Massacre in Pennsylvania, with a marker at the former National Labor College. [ed: see Katz comment below, NLC is still in operation]. I trudged through all of the required forms, and supported the application with several dozen letters written by high school teachers from across the country, who spent a week in Baltimore studying the strike.

A representative from the Maryland Historical Trust was very supportive—so supportive that she basically let me write the text for the marker, except she insisted on listing Martinsburg first–as was an official of The Maryland Stadium Authority, which has control over the location. The marker stands right behind the original B & O station, on a main walk and light rail system and will be passed—if not seen—by hundreds of thousands of baseball fans every season. Location, location, location.

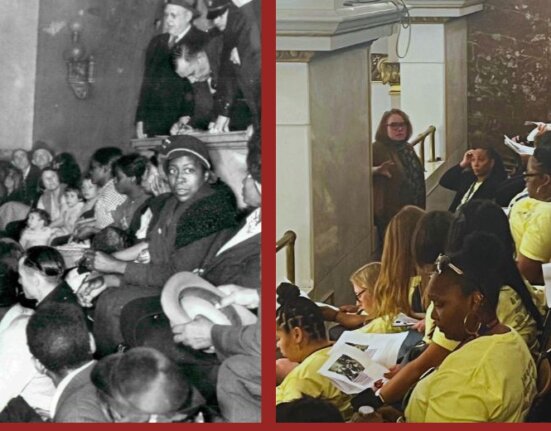

The unveiling was a great ceremony, with supporters from various unions and community groups, with a reception at The Irish Railroad Workers Museum, another almost unknown location. While Johns Hopkins University maintains Evergreen House, the 48-room mansion owned by John Garrett, there was no memory of the B & O workers until Thomas Ward, a historian of Baltimore’s Irish Community and a former baggage handler for the B & O, bought two row houses and restored them as if railroad workers of the 1870s were living there.

Every labor historian should consider a project like this: it sharpens our sense of history, builds public—and permanent—visibility with a marker and will be an occasion for focusing public resources on the workers’ history of your area.

For coverage of the unveiling, go to the Facebook Photo Album and Description by Bill Hughes; and see the Baltimore Brew Article on the 1877 Strike Monument.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.