“Protest” or “hunger strike?” Officials at the Robert N. Davoren complex (R.N.D.C.), a jail part of the Rikers Island correctional facility, have offered conflicting statements on the actions of a group of detainees who protested their living conditions on January 8th. The New York Times described the refusal of approximately 200 detainees—many of whom are awaiting trials and have yet to be found guilty—to eat cafeteria food as a “hunger strike.” Detainees interviewed explained that they were protesting a high number of COVID-19 cases , filthy living conditions, and degrading labor involving cleaning up feces and vomit in cells. But representatives of Department of Correction assured reporters that this was not a strike; these are the actions of “a group of detainees” who chose instead to eat commissary food.

What we call the fight of incarcerated and detained peoples for better working and living conditions—intertwined and inseparable in prisons and jails—shapes public perception of their struggles and how historians view the complex history and nature of prison labor.

An example of how important phrasing is and what we call protests that take place among prisoner workers can be found in the history of Japanese American incarceration during WWII. Many historians have accepted that using the phrases “internment” and “relocation centers” to describe the forced removal of 120,000 Japanese Americans (the majority citizens) from their homes along the West Coast and their detention in concentration camps is incorrect and rooted in government euphemisms. “Incarceration” is the more apt term as it implies a unique situation where not just “enemy aliens” but citizens were held behind barbed wire for suspected, but not proven in a fair trial, subversion. And if incarceration is the appropriate word, then referring to Japanese Americans as prisoners or incarcerees is more accurate than describing them as “evacuees” or “internees.”

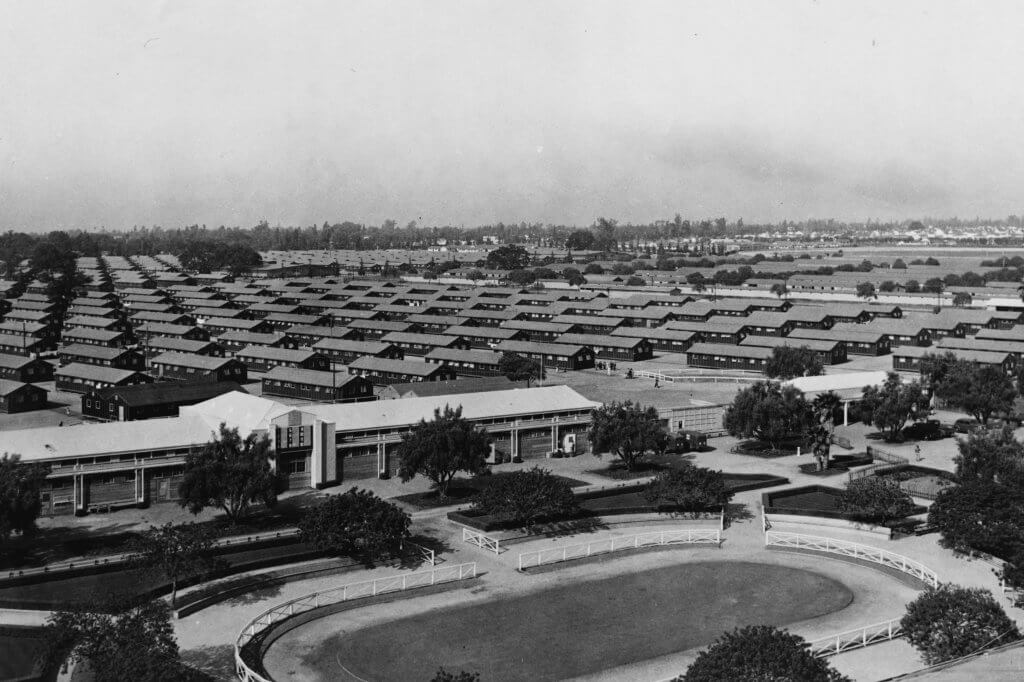

An important part of the incarceration project was using coerced labor to complete infrastructure projects, make the camps self-sufficient, and work for companies contracted by the military to produce war materiel. Technically, camp directors could not force Japanese Americans to work and those who agreed to do so signed a contract and received monthly wages (far below the national average) for their labor. But incarcerees needed to purchase goods (like work clothes or special foods for dietary needs) which required money. Camp directors also reminded Japanese Americans that when their loyalty to the United States was doubted, work was a way to prove that they were dedicated to the war effort.

If the government expected incarcerated Japanese Americans to work and used prison conditions to coerce them to do so, then what the incarcees performed was prison labor, one example of a longer history of incarceration in the United States. And when they protested their working and living conditions, these were prison strikes, but were so often described by the administration and the public as riots or the work of bitter troublemakers who sought to undermine the United States. The labor strikes conducted by Japanese Americans highlight the nexus between the unique conditions of coerced labor while detained and the demands that were often like those of free and organized laborers across the United States.

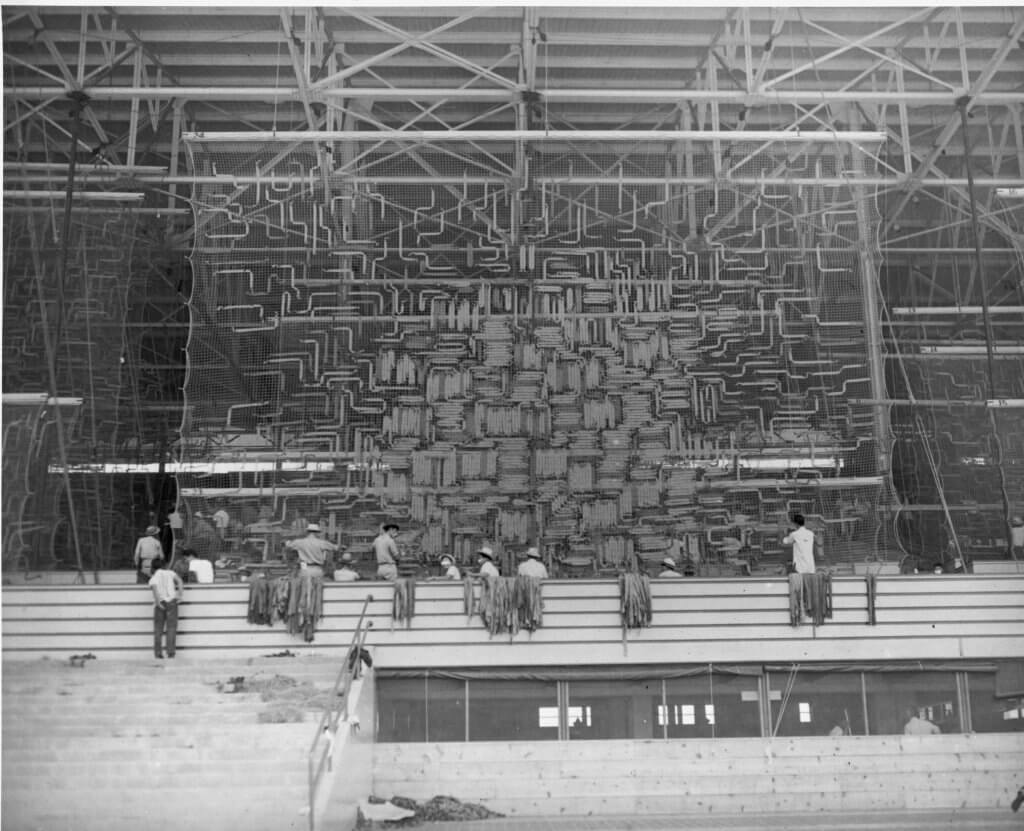

On June 16, 1942, more than 1,200 Japanese Americans employed in an on-site camouflage netting factory at the Santa Anita detention center outside of Los Angeles walked off the job. Earlier in May, a private contractor who requested to use detained Japanese Americans to weave and box the large netting set up shop after center directors determined the pay scale for various tasks, ranging from eight to sixteen dollars a month, and the length of a contract (sixty days). The factory seemed to be humming along by June so it came as a surprise to Russell Amory (the center director) that net workers went on strike. The walk-off was short-lived–two days later most of the workers had returned—and Amory used the limited duration to argue that this wasn’t a large-scale strike but rather the work of a “few agitators” with no clear goals except to protest “the serving of sauerkraut for dinner.” By all public accounts, this was nothing more than the work of a small bunch of “agitators” with no real ground to stand on, similar to how representatives from the R.N.D.C. described the hunger strikers.

But a petition later found by FBI agents while doing inspections in multiple housing units revealed more substantive demands and a more systematic purpose to the strike. The pamphlet addressed to “Nisei Camouflage Workers” was anonymous, but FBI agents suspected that it was the work of strike leader Shuji Fujii, an American citizen employed in the boxing division of the camouflage factory. The pamphlet drew attention to the unsafe working conditions of the camouflage net makers which required them to box and weave nets with no gloves and no masks, resulting in trips to the infirmary with blisters and sores on their hands and dry, bloody coughs from inhaling fibers. “Where is DEMOCRACY? There is democracy for [the] Japanese race, even if we are born in this country—first we are in camp, now we are worse than prisoners,” the petition stated. This was more than just a few agitators protesting having sauerkraut at meals. And though the strike was short-lived, it inspired other work stoppages across Santa Anita.

The strike at Santa Anita is just one of many instances of labor protests initiated by incarcerated Japanese Americans. The fall and winter of 1942-1943 saw a series of work stoppages at camps and detention centers often described as “riots” but were Japanese Americans attempting to exercise their labor rights even while incarcerated. The larger significance of the work performed by incarcerated Japanese Americans, their protests of their living and working conditions, and the public perception of their strikes still resonates in contemporary discussions of the labor rights of prisoners and their right to fight for them.

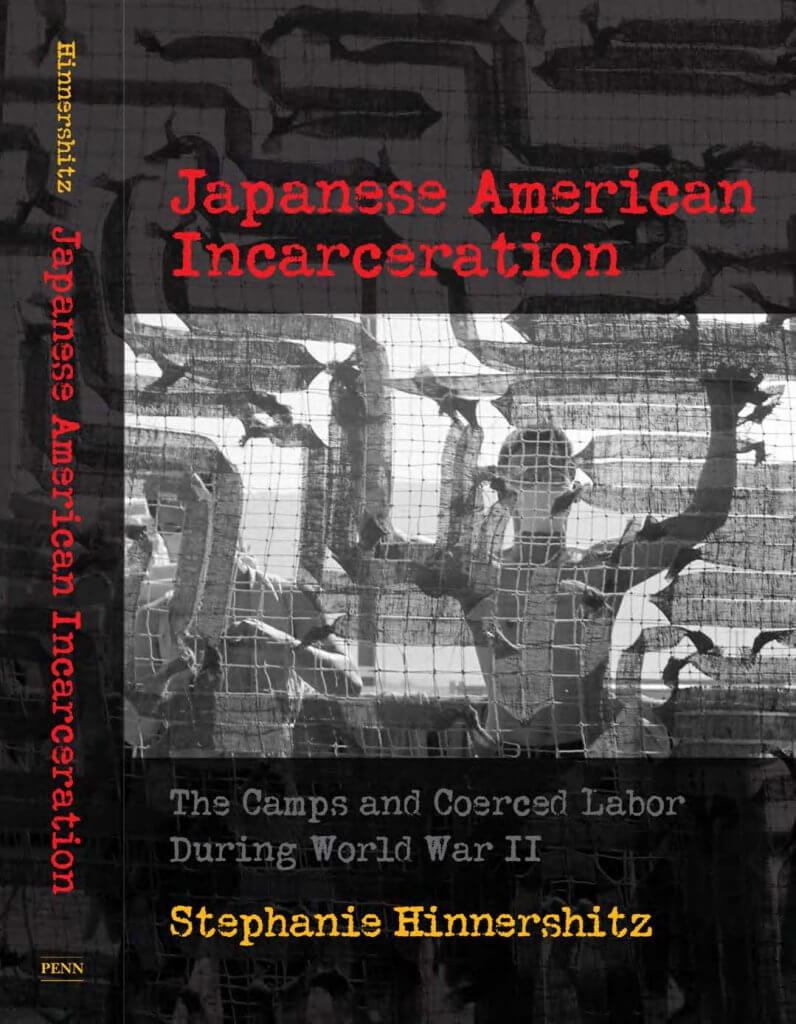

Steph Hinnershitz is a historian with the Institute for the Study of War and Democracy at the National WWII Museum and earned her PhD from the University of Maryland in 2013. Her speciality is the American home front and civil-military relations during WWII and her most recent book, Japanese American Incarceration: The Camps and Coerced Labor during World War II, was published in 2021 with Penn Press.