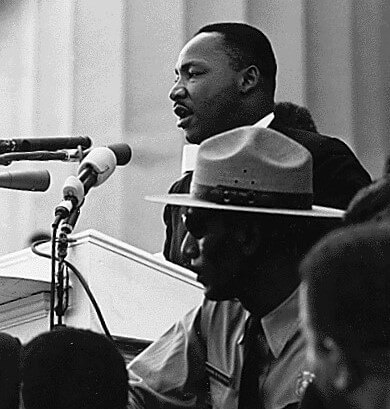

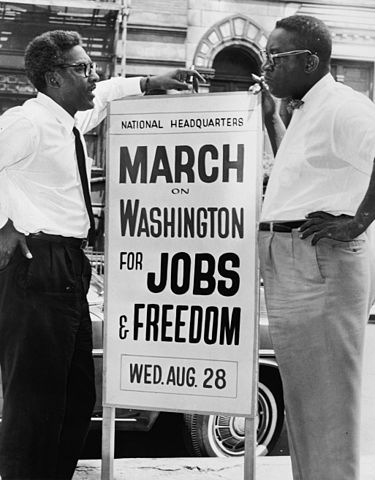

On August 28, 1963, more than 200,000 people converged at the Lincoln Memorial in a March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The assembly occurred in a period of heightened black freedom struggle that was most ferocious in the Deep South but also relentless across the Upper and Border South, Northeast, Midwest, and West Coast. The event remains lodged in the popular memory because of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s now mythic “I Have a Dream” speech, which solidified his status as the civil rights movement’s chief avatar. But the march more fundamentally represented a coming together of activists who had been campaigning locally around a range of issues – quality schools, open housing, access to public accommodations and the meaningful exercise of the vote, as well as community control of police, equitable metropolitan planning and development policies, and fair employment in retail, finance, municipal workforces, and the skilled construction trades. Notwithstanding Malcolm X’s famously irreverent characterization of the march as a “farce on Washington” because of the organizers’ deference to the John F. Kennedy White House, the gathering dramatized before a national public the movement’s grievances against southern U.S. apartheid, northern racism, and federal recalcitrance, while reinforcing the necessity of social reform.

Fifty years after the fact, we can expect to see commemorations over the next several months by movement veterans, media commentators, elected officials, and professional scholarly organizations like the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. What particular significance does the march have for labor and working-class historians?

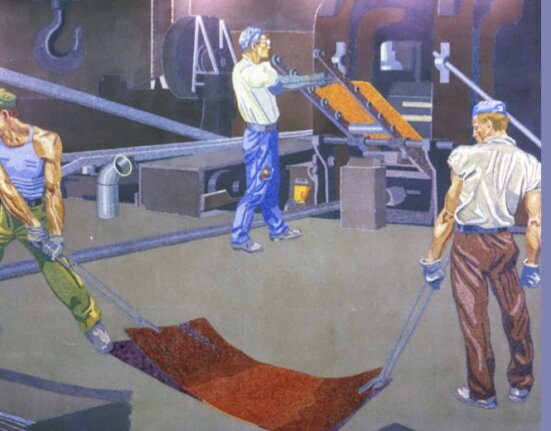

The march provides an opportunity to unsettle standard depictions of the civil rights movement as bred and led by a striving post-World War II black middle class. While the mobilization for the event included such organizations as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW), and the National Urban League (NUL), the call was spearheaded by A. Philip Randolph’s Negro American Labor Council (NALC). As president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (the first all-black trade union to be recognized by a major corporation), Randolph had initiated a similar March on Washington Movement during the 1940s in response to racial discrimination in the wartime production industries and armed forces. Publicized as a demonstration for “jobs and freedom,” and with black labor icon Randolph as its titular leader, the 1963 rally asserted the centrality of fair and full employment, and union rights, to a racial justice agenda. Indeed, organizers of the march attracted the support of the United Auto Workers (UAW) and several other unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO).

As one of the march’s prominent banners illustrated (“Civil Rights Plus Full Employment Equals Freedom”), black protest and organized labor walked in tandem during this period, though not always in harmony. The NALC, for instance, had emerged in the early 1960s out of Randolph’s frustrations with the AFL-CIO merger in the 1950s, most especially the federation leaders’ indifference to the pervasive racial discrimination within the House of Labor. Likewise, NAACP labor secretary Herbert Hill had doggedly fought for the desegregation of labor organizations since assuming the position in 1951. Further, the stultifying anti-radicalism of that era, promoted by liberal Cold War labor leaders including Randolph and Hill, undercut far-reaching black freedom goals. More generally, this fostered a bureaucratic orientation that emphasized securing better contracts for union members over organizing the unorganized, or advancing “social unionist” initiatives to improve the quality of life of working people across the board. Nonetheless, the relationship between labor and black freedom politics, however tumultuous, bore witness to a racial-class linkage anchoring civil rights battles.

To state the point more boldly, the 1963 March on Washington symbolized a “Negro revolt” for full political and social citizenship that – however diverse its participants and leaders – contained a distinctly black working-class core. While this working-class nucleus included trade unionists like Randolph, it also encompassed African Americans on the outskirts of post-World War II organized labor – domestic workers, means-tested welfare recipients, common laborers, rural sharecroppers, and the growing ranks of unemployed youth. This was evident in the backstage conflict at the march involving the prepared speech by SNCC chairman John Lewis, who regarded the Kennedy administration’s pending civil rights bill as too little too late in addressing the political exclusion, economic exploitation, and state violence experienced by the black southern laboring majority. The intersection of working-class and black politics is perhaps easier to recognize in King’s own trajectory after 1963, which scholars such as Michael K. Honey and Gerald D. McKnight have explored. Outspoken in support of collective bargaining rights and economic justice since the late 1950s, King continued a journey that led him to the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign and the crucible of the Memphis sanitation workers strike where he was assassinated. It is worth noting, too, that it was the wildcat insurgency of the black garbage workers themselves that aroused the involvement of black middle-class leaders and white union officials, paving the way for national figures like King to intervene.

Hopefully, the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington will be an occasion to do more than monumentalize a date, add resonance to King’s birthday this year, or augment celebrations of the new MLK Memorial. Instead, as labor and working-class historians, we can use this year as a signpost in much the same manner that activists in 1963 used the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation. That is, we can employ the March on Washington as a historical point of departure for publicizing issues of racial and economic injustice that beset us today. These issues include black unemployment, which as of October 2012 stood at a staggering 14.3 percent, or nearly twice the national jobless rate of 7.9 percent. They also involve the shameless campaign against collective bargaining rights, even in once strong union bastions like Wisconsin and Michigan. They consist of blatant efforts to subvert the voting rights of African Americans, Latinos, and low-income, elderly and disabled people of all racial-ethnic backgrounds. These issues cover the deadly “Stand Your Ground” laws in Florida and other states, rooted in a fear and criminalization of youth of color. They also encompass racialized mass incarceration and its wide-ranging effects: As sociologist Becky Pettit argues in Invisible Men: Mass Incarceration and the Myth of Black Progress, the rate of black imprisonment skews national survey data about African American work force participation, wages, and educational attainment, effectively hiding the extent of contemporary racial disparities.

Observing this anniversary will be meaningful only insofar as it enables us to measure the extraordinary transformations that have occurred since 1963, the setbacks that have followed, and the current forms of stratification that beg our attention, creativity, and labor right now.