The pundits always seem to miss the politics of capitalism in their effort to explain inequality.

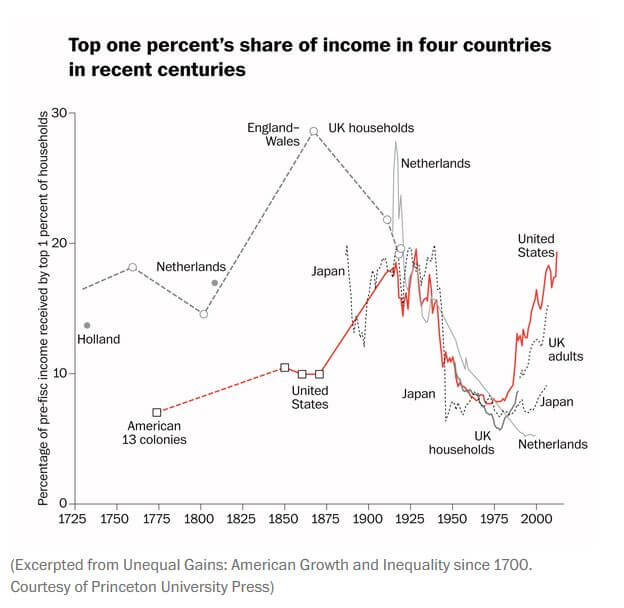

It looks like a new book by Peter Lindert and Jeffrey Williamson, Unequal Gains: American Growth and Inequality Since 1700, is gaining traction among the punditry class, following last year’s nod to Thomas Piketty’s Capital. Unequal Gains engages in a long range historical comparison of the top 1% across time and nations. Unlike Piketty (and Saez), who used tax records back to 1913 to understand growing inequality, Unequal Gains goes back to the colonial era. Certainly their suggestion that despite slavery, “incomes were more equally distributed in colonial American than in any other place that can be measured,” will be widely debated. I haven’t read the book. But their “history lessons,” written here and excerpted below, raised an eyebrow:

American history suggests that inequality is not driven by some fundamental law of capitalist development, but rather by episodic shifts in five basic forces – demography, education policy, trade competition, financial regulation policy, and labor-saving technological change. While some of these forces are clearly exogenous, others – particularly policies regarding education, financial regulation, and inheritance taxation – offer ways to check the rise of inequality while also promoting growth.

Pundits such as Jeff Guo at the Washington Post used the book to characterize recent escalation of U.S. inequality as a by-product of globalization: “technological change and globalization have widened the gap between skilled workers and less-educated workers.” The “boom in the financial sector” is a culprit, and that is written as though it was somehow a natural occurrence. But Guo acknowledges that the recent figures show inequality continuing to grow.

Guo suggested we are moving into “uncharted territory.” Nah. The course we are on has been contextualized brilliantly by Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin in The Making of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy of American Empire, and this is the best book for understanding the politics of inequality. Panitch and Gindin traced the role of the U.S. state in creating and continuing to keep afloat the circle of power based on inequality. Rather than inanimate “globalization,” they show state power and state institutions, primarily U.S.-based, keeping global capitalist power structures afloat and reproducing it’s 1%. Moreover, they examine closely executive power in the creation and recreation of choices. And their predictions continue to unfold.

Panitch and Gindin trace a concentration of decision making that produced our current system. These were amplified under the Obama administration. There were many state-based interventions that the Obama administration could have used to deal with the 2008 economic crisis. But he instead chose a path laid out in early decades.

Under Obama’s administration, income inequality continued upward to an escalation point unprecedented in American history. Little of this had much to do with Congress at all, though liberal commentators have explained Obama’s contribution to growing inequality as a by-product of deadlock and Republican power. Advised by remnants of Clinton-administration and Wall-Street advisors, the Obama administration worked with the Fed and the Treasury, including but not limited to a top-down qualitative easing, with not only the U.S. but world capitalist structures in their framework. It was a path blazed from World War II, and one that was firmly in the executive power. These institutions continued to elevate the financial sector in capitalism, which is currently driving outsourcing, downsizing and robotization, processes that will continue to increase inequality. While saving global capitalism from collapse, the state contributed massively to reinforcing the existing power structures that have brought rising economic inequality. Given the link to the Clinton administration, we are in a kind of long-term tribal oligarchy; Hillary Clinton is likely the next in charge of this system and will be the next to confront another global crisis. The range of voices is actually quite narrow at the top.

Panitch and Gindin rejected arguments that globalization eroded state sovereignty. They show however that U.S. interventions have constrained social-democratic solutions, whether in Western Europe or Brazil, time and again.

This recent crisis has elevated the U.S. role in the global capitalist empire, as the U.S. kept institutions that had invested in Ponzi schemes across the globe afloat. We in the U.S. are in the belly of the beast, more than ever.

While during the election season, we have heard over and over the assertion that the executive branch can’t do anything about economic inequality without cooperation of Congress, it’s important to remember that almost none of this was done through Congress. In the world of decision making, the state is smaller than ever. A small handful of the 1% operates to save the system that reproduces the 1%. Only by exposing these operative state mechanisms can we fully understand the political role of the executive branch in the creation and sustaining of the American capitalist empire.

At the end of their story, Panitch and Gindin remind us that this kind of concentration of power also offers us a solution: The take-over of financial institutions as public utilities has to be on the political agenda of our movements. Without this, they will continue to continue to create more crises and more concentrated global power in Washington. It’s the perfect circle.