Public education today is at the center of an unrelenting assault on the American labor movement. This is no accident; by some measures, nearly 40% of unionized workers in the United States work in education, and organized educators have proven vocal opponents of neoliberal politicians and policies. As a consequence, educational unions have been singled out for destruction by Republican governors, state legislatures, and courts as part of a broader attack on public sector organizing. From Wisconsin to California, these opponents challenge not just the gains made by public-sector unions, but their very right to exist.

Teacher unions around the country are fighting back by building coalitions with the students and parents they serve. Working-class communities have been hit hardest by school closures, privatization plans, and budget cuts carried out in the name of right-wing education reform, and new grassroots movements for school equity are emerging in response. Through partnerships with these activists, teachers can challenge even the most powerful and well-connected opponents, as the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) demonstrated in their 2012 organizing campaign. By “linking their fight to a community struggle and placing it in a broader political framework” Tom Alter wrote in Labor, the CTU “exemplified the essence of social movement unionism.” Their success has inspired locals across the nation to follow their lead.

As teacher unions build these new alliances, they are reconnecting with the classroom workers and union members who are best positioned to bridge divides between schools and communities: paraprofessional educators. “Paras” are everywhere in schools: they aid teachers with overflowing classrooms, instruct small groups in bilingual programs, offer one-on-one tutorials to special-needs students, and provide care and supervision in lunchrooms, hallways, and schoolyards. Paras are far more likely than teachers to hail from the neighborhoods where students live, and they leverage this local knowledge to improve instruction and facilitate communication between teachers and parents. In 2012, CTU President Karen Lewis recognized that paras were valuable conduits between her union and local residents. “Paraprofessionals, those are the people that actually have experience with children in that neighborhood, because they by and large work in the neighborhood where they live” Lewis noted in an interview with Dissent. “We’re working together with them because school closings affect all of us.”

Despite the essential services they provide, paraprofessional salaries remain low. In some cities, paras are being priced out of gentrifying neighborhoods along with the working-class families they serve, as Educators for a Democratic Union (EDU), a caucus of the United Educators of San Francisco (UESF), argued recently. In many instances, paraprofessionals take on second and even third jobs to make ends meet, as New York City paras reported to this author at a conversation about paraprofessional organizing this fall on Staten Island.

Even more troubling have been the attacks on paraprofessional jobs themselves, a process that has disproportionately affected working-class African-American and Latina women in urban school districts. The layers of local knowledge that paras bring to a diverse range of tasks are not easily measured by market-based analyses, and corporate reformers like former New York City Schools Chancellor Joel Klein have sought repeatedly to cut these positions. In 2003, the United Federation of Teachers sued Klein for racial discrimination after he announced nearly 1,000 layoffs, joining community groups in protesting this attack on woman workers and the value of their labor as educators.

In short, despite being members of teachers unions, paras are regularly faced with the low wages, precarious tenure, and workplace marginalization that characterize non-union jobs in our post-industrial economy, particularly those held by women of color. As teachers unions rediscover the paraprofessionals in their midst, they are discovering that unionization, in its current form, has not always guaranteed security or prosperity for these educators. To be sure, union membership offers significant benefits – health care, retirement packages, and opportunities for further education – that do not exist at similar wage levels in the private sector. Most of the insecurity paras face comes from budget-slashing and school system restructuring that have ravaged the entire educational workforce, and which teacher unions are fighting as best they can.

With all of this in mind, however, it is still important to observe that the mere presence of paraprofessionals in teacher unions has not generated robust alliances between communities and educators, nor has it ensured the full and equal incorporation of paras into schools and union locals. These issues are deeply intertwined: to mobilize paraprofessionals as coalition builders, the labor movement must also empower paras in the workplace and the union hall. With organizers around the country trying to do just that, it is an excellent time to look back to the era when paraprofessionals first joined teacher unions, both to understand how an earlier generation of organizers built alliances and to understand the challenges that they faced.

Paraprofessional jobs emerged in the mid-1960s, the product of grassroots freedom struggles and federal antipoverty funding. In cities across the country, Black and Latino families took to the streets to demand equal opportunity for students, increased community participation in schools, and the integration of the educational workforce. At the federal level, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA) provided millions of dollars of new funding to local education agencies to combat poverty in schools. Responding to the groundswell of activism around them, local school boards used these funds to hire thousands of people, primarily the mothers of schoolchildren, to work in neighborhood schools.

Administrators and activists hoped paraprofessional programs would accomplish three things at once. They would improve instruction and discipline by bringing local knowledge into classrooms. They would enhance communication and cooperation between schools and communities by acting as conduits between parents and teachers. Finally, they would create not just jobs but careers for low-income women through opportunities for teacher training.

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) considered opposing the ESEA entirely on the grounds that it provided no direct funding or protection for teachers. The AFT was particularly suspicious of paraprofessional educators, whom many teachers feared would act as spies and scabs. However, on the AFT’s executive council, progressive members Richard Parrish of New York – who had led the desegregation of AFT locals in the 1950s – and Rose Claffey of Massachusetts challenged the union to reconsider. While the union did not reject the ESEA outright, many leaders and locals watched the development of new programs with suspicion.

What these unionists saw happening in the classroom surprised and impressed them. Paras, one parent activist remembered, “made themselves essential,” and teachers who worked with them quickly realized their value. Over 200 New York City teachers surveyed by the UFT returned positive evaluations of their paras just one year into the program, describing them as “essential” and “excellent.” Paraprofessionals, in the same survey, noted their pride in their new roles, particularly their work in “establish[ing] a closer relation between parents and schools.” Claffey reported similar reviews in the cities of Massachusetts. In talking to their new colleagues, teachers realized that paras were poorly paid, and that administrators regularly denied them promised opportunities for advancement. The moment seemed ripe for organization.

The emerging solidarity between paras and teachers, however, was nearly derailed by clashes between teacher unions and advocates for “community control” of schools in African-American and Latino neighborhoods. In New York City, a newly-elected local school board in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, Brooklyn, unilaterally transferred 19 white teachers out of the largely Black and Puerto Rican district in May of 1968. When the teachers were not reinstated that fall, the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) struck, closing schools for nearly six weeks across the city. While the union claimed it was defending due process for its members, many Black and Latino parents experienced theses strikes as a racist assault on their children’s educations, as scholars Daniel Perlstein, Jonna Perrillo, and Jerald Podair have shown.

Paraprofessionals were caught in the middle of this maelstrom. Many paras crossed picket lines to teach the children of their communities, but many others stayed out in solidarity with their teacher colleagues (albeit unprotected by the union). However, by the time the State of New York suspended the “community control” experiment in December of 1968, the level of animosity between teacher unions and communities of color in New York City seemed to foreclose the possibility of paraprofessional organizing.

Nonetheless, the UFT launched a campaign to unionize paras in 1969, just weeks after the strikes had ended. Richard Kahlenberg, in his biography of UFT President Albert Shanker, Tough Liberal, cites Shanker’s embrace of the idea as the decisive factor in the campaign. Shanker’s leadership was undoubtedly important, but my dissertation research demonstrates that two other factors fueled this drive. One was the pressure exerted by left voices and caucuses within the UFT. Richard Parrish, who broke with the union to support community control, cited unionizing paras as a route to mending fences in an article excoriating Albert Shanker in Labor Today in 1969. A new UFT caucus, Teachers for Community Control (which later became the Teacher Action Caucus), also supported unionizing paras, in order to build solidarity with freedom struggles and make the union more responsive to community demands.

Most importantly, organizing took place in the classroom, where teachers and paras developed bonds of feminist solidarity. Despite their different experiences of race, class, and urban geography, paraprofessionals and teachers frequently found common ground in their lives as working women and working mothers. As one program coordinator observed, “these women want for their children what middle-class people want for theirs,” an observation echoed in oral histories and documents from the period. At a time when divides of race and class seemed insurmountable to many New Yorkers, the shared labor of schooling and motherhood brought educators together.

These commonalities helped to nurture the UFT’s organizing effort, which was led by Velma Murphy Hill, a veteran civil rights organizer from CORE and the NAACP. Leading a team of women who had worked as paraprofessionals, Hill traveled the five boroughs tirelessly, gathering paras together and talking to community organizations, convincing activist mothers that unionization would note mean the end of paraprofessionals’ local commitments. The teachers who worked with paras also recruited them into the union, and later traveled to convince other teachers to support paras with the threat of a strike when New York City’s Board of Education refused to bargain with them in 1970.

Shanker, a master campaigner, understood that bringing thousands of Black and Latina women into the union and improving their wages, benefits, and training opportunities would be a political coup, as well as a way to increase union rolls (and dues). Shanker supported Hill’s efforts with his own letters and speeches, and in 1969, the UFT won the paras’ election over AFSCME District Council 37. After the union mobilized teachers to support a potential para strike in June of 1970, the New York City Board of Education came to the table. Paraprofessionals signed a landmark contract in August that provided a 140% wage increase, health and retirement benefits, and paid time off for paras to train as teachers at the City University of New York (CUNY). Writing in the New York Amsterdam News, Bayard Rustin called the contract “one of the finest examples of self-determination by the poor.”

The UFT paraprofessional contract became a model for AFT locals across the nation. Unionization was swift: from 1970 to 1985, the AFT organized as many paras – 50,000 – as it had organized teachers in its first fifty years. The impact of this organizing was enormous. It preserved jobs created by the War on Poverty well past the dismantling of many social welfare programs in the 1970s and 1980s. It provided a measure of job security and decent wages for thousands of mothers in neighborhoods ravaged by unemployment, government neglect, and deindustrialization. It brought thousands of women, African Americans, and Latinos into the labor movement, and it created educational opportunities in which paraprofessionals earned high school diplomas, associate’s, bachelor’s, and master’s degrees. Thousands became teachers and principals, though never as many as hoped for, as the process often took six years or more. By all of these measures, the unionization of paras was a significant victory for both the freedom struggle and the labor movement.

And yet, as the present situation makes clear, these significant gains were not, in themselves, sufficient to produce the social justice unionism that many paras and progressive unionists envisioned in the 1970s. While this history is far from a story of simple co-optation, Shanker and many other AFT leaders routinely cast the legitimate struggle of the paraprofessionals against the illegitimate efforts of community control activists. This rhetoric negated the deep relationship between paraprofessional work and radical visions of community schooling, and limited the building of coalitions between schools and parent activists. Paras, teachers, and parents developed many innovative partnerships at the school and local level throughout the decade – Velma Hill’s paraprofessional chapter in New York led organizing workshops, for instance – but this commitment to school-community partnerships did not trickle up to national union policies. Additionally, the AFT and its locals incorporated paraprofessionals, and counted their votes for state and national delegations, in ways that limited their power within the union.

As is true today, it was not union bureaucracy but assaults from the right that did the greatest damage to transformational visions of paraprofessional unionism. Budget hawks used fiscal crises at every level of government to slash funding for para jobs and obliterate teacher-training programs in the mid-1970s. New York City’s brush with bankruptcy in 1975 wiped out CUNY’s para training program, which had enrolled roughly 6,000 paras a semester – out of 10,000 eligible women – every year prior. Ronald Reagan’s across-the-board cut of 20% to federal educational spending meant even further layoffs and fewer opportunities for advancement, a combination that relegated many paras to precarious positions in schools.

Then as now, conservative attacks on public schooling were the primary challenge to community-based education, but the weakening of school-community linkages in paraprofessional programs certainly made it harder to defend educators and education from cuts in the 1970s and 1980s. This makes it all the more encouraging to see teacher unions today reconnecting with paraprofessionals. Locals (discussed above) have built paras into community organizing strategies, while the AFT has focused attention on the role of paraprofessionals in the ongoing debates around the reauthorization of the ESEA (known today as No Child Left Behind). AFT Secretary-Treasurer Lorretta Johnson invoked her own experience as a para in urging Congress to return to the focus of the law to addressing inequality, and the AFT recently wrote to the Senate urging them to keep paraprofessional qualification requirements in the new legislation in order to incentivize funding for training and advancement programs. All of these efforts, from the local to the national level, suggest that teacher unions are once again seeking to empower paraprofessionals in their schools, their neighborhoods, and their union halls.

Empowering these community-based educators is one of many routes to realizing AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka’s call to “turn the labor movement back into a movement that fights for the interests of all working people” at the 2013 AFL-CIO convention. Mobilizing the connections paraprofessionals have to students and parents can make the teacher unions more responsive to their needs, and creating new opportunities for paraprofessional advancement can demonstrate the power of the labor movement to working-class communities where jobs and training opportunities remain in short supply. By utilizing local knowledge in education and organizing, unions and communities can demonstrate that elite outsiders are not the only ones with plans or resources for reforming and improving education.

In January, LAWCHA members gathered in New York City – the birthplace of paraprofessional organizing – to hear “creative solutions to some of the serious challenges labor faces.” As Lara Vapnek reported, “forms of organizing are changing, but key goals are enduring”: dignity, respect and a living wage. For teacher unions today, a renewed focus on paraprofessionals marks both a new form of organizing and a return to longstanding commitments: building a broad, bold movement to promote and defend public education.

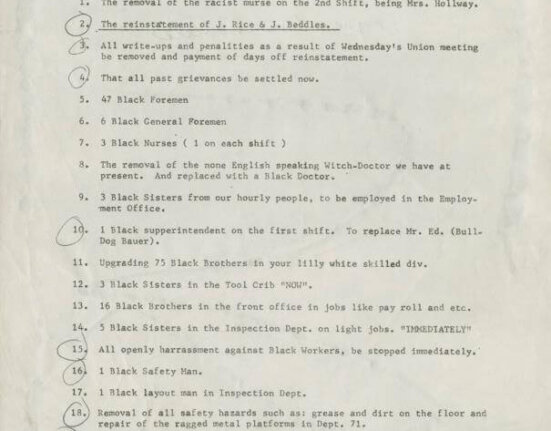

Related Document

The AFT’s 1973 Pamphlet, “Organizing Paraprofessionals.”

Download the .PDF (5mb)

This twenty-page booklet offers a concise and fascinating glimpse of how the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) organized paraprofessionals in the early 1970s. The booklet describes the origins of paraprofessional programs and gives a sense of paraprofessional work as it was performed in 1973. It captures the language of the “paraprofessional movement,” the strategies the union deployed in organizing these workers, and the ways in which the union incorporated paraprofessionals. It is a document with soaring rhetoric, but it also reveals the limits placed on paraprofessional power by institutional practices. The pamphlet makes an excellent discussion item for undergraduate and graduate students, teachers, paraprofessionals, and union organizers.

I have used this pamphlet in a variety of presentation and teaching settings, including in discussions with current paraprofessionals. What follows are some suggestions on how four different sections within the pamphlet might be used, and questions that these pages might generate. Each of these sections can be used alone, or they can be combined into a larger conversation about education and organizing. For those with knowledge of the history and present practice of teacher unionism, this document provokes lively discussion the particulars but it can also serve as an introduction to union organizing for students encountering labor history for the first time. It can also be used to connect the efforts of teacher unions to other major forces and themes in mid-20th-century US history: the black freedom struggle, the War on Poverty, federal spending on education, and the women’s movement.

As an important caveat, paraprofessional unionism and the organizational structures of the AFT have, of course, developed and changed significantly since 1973. Those interested in current AFT policies around paraprofessionals should consult the AFT’s Paraprofessionals and School-Related Personnel Division (PRSP), or the relevant divisions of local unions.

- “Background” and “Who are the Paraprofessionals?” (pages 1-3) This section of the document outlines the origins and goals of paraprofessional programs as the AFT understands them. It introduces important context, including War on Poverty legislation, demands for better communication between school and community, and the need to improve instruction in overcrowded classrooms.

- The first sentence of the “Background section reads: “The paraprofessional movement is a nationwide phenomenon.” The last sentence reads: “paraprofessionals are here to stay!” What does it mean for the AFT to speak about these “community people” (as they are described) in this way?

- Note the immediate mention of War on Poverty/Great Society funding: the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) and the Education Professions Development Act (EPDA). Paraprofessional jobs were funding largely by this legislation. How does this compare to federal funding for education today?

- Consider the four-part “rationale” that the AFT outlines for paraprofessional work. What does it tell us about the union’s goals for these workers? The fourth item reads “hire persons who would meld the school and community.” With some notable exceptions, it is rare to see such language in official descriptions of paraprofessional programs today. Why? What has changed?

- Consider the descriptions of paraprofessional labor in both sections. How do they compare to the work that paraprofessional educators do today? What implicit assumptions about gender, race, and class are built into these roles? What kinds of formal skills and local knowledge do these tasks require? What limits does the AFT specify for the work of paraprofessionals (in particular, note the repetition of the theme that paras are always to be “supervised” by teachers).

- “Vertical Unionism”: Why does the AFT seek to become a “vertical union”? What benefits might result, and what challenges?

- Organizing and Administering a Paraprofessional Chapter (pages 3-12) This section comprises the bulk of the pamphlet, guiding unionists in organizing a paraprofessional chapter. Read as a whole, it generates lots of questions: What strategies are employed? What do these strategies tell us about the challenges of organizing paras? How do they compare to today’s organizing campaigns?

- “Organizing a Paraprofessional Chapter”: What institutional roadblocks and hurdles do school systems, federal legislation, and union constitutions present to paraprofessional organizers?

- “Representation Campaign”: Note the emphasis on creating a “group of paraprofessional leaders” and on “person-to-person” campaigning. Under the “Building Representative” subheading, note the emphasis on having teachers recruit the paras they work with, and the importance of holding “meetings or socials” between teachers and paras. Why might this contact be important? Does it still take place in schools and teacher unions? What issues might arise between teachers and paras? What issues might paras share with one another? What might this tell us about how teachers and paras related to each other outside of work?

- “Questions and Answers in the Campaign”: What do these “FAQs” reveal about potential tensions between teachers and paras, and the concerns that both have about their jobs and careers in 1973? What do the answers suggest about the AFT perspective? How, if at all, has any of this changed in today’s schools and unions?

- Pages 8-11 focus on campaigning and education (“the heart of the campaign”). On what grounds does the AFT recommend appealing to paras? What kinds of benefits are discussed, and what kinds of slogans are suggested? What does it mean (for teachers and paras) to describe themselves as a “united team”? Do paras and teachers today consider themselves a “united team” in schools?

- “Administering the Chapter”: What does the AFT recommend prioritizing for paras once unionization is successful? What opportunities can AFT locals provide?

- Appendix: “AFT Convention Resolutions Regarding Paraprofessionals” (pages 13-16) These resolutions were passed in the summer of 1970, shortly after the first successful paraprofessional organizing drive in New York City. They can be read separately, though they also inform much of the language in the preceding pages.

- The resolutions begin with three points of information that “research discloses” about paraprofessionals? What do we make of the language and content of these three items? Is this how we speak about paraprofessionals today? What do these three items reveal about the era in which they were written, and the possibilities that the AFT and professional researchers saw in paraprofessional programs?

- Note that the third resolution commits the AFT to support paras in becoming “fully trained and certificated professionals.” Teacher recruitment and retention in low-income neighborhoods, then as now, was a major challenge, and para programs were seen as one way to address this. Why is this? What strategies do we deploy today to address “teacher shortages?” How do para programs differ?

- In the subsection “Support for and Organization of the Paraprofessional” the AFT suggests that the interests of paras and teachers are aligned, and argues for the promotion and expansion of paraprofessional programs. Later on, the resolution on “Paraprofessional Programs” expands on this, stating “the need to have more paraprofessionals drawn from the local community working in our schools is obvious.” Remember that these resolutions were written only 18 months after New York City’s fight over community control. Did all teachers (or paras) consider such a statement “obvious”? Fast-forward to today: do they still?

- “AFT Constitutional Provisions for Paraprofessionals.” Here, the AFT outlines how locals who add paraprofessionals to their ranks will be funded by dues, taxed, and counted for the apportionment of delegates for state and national conventions. Note, in particular, that locals pay a per-capita tax of one-half the regular rate for paras, and also that paras “shall be counted in determining the delegate strength of the local at ½ of the constitutional formula.” How might such a formula affect paraprofessional power within local unions? What limits does such a construction impose? How might a clause that counts people fractionally be read, particularly in light of the racial dynamics involved? Dues and funding structures seem to be the explanation for this – what do we make of them?

- “Sample Constitution for Paraprofessional Chapter” (pages 16-20) This sample constitution served as a template for many paraprofessional chapters. It, too, can stand alone, though it works well with the other portions of the document, and certainly informs the sections on organizing and administering paraprofessional chapters.

- Note the “Objectives” listed in “Article II.” What kinds of goals does the AFT have for paraprofessional chapters? In light of the context in which paraprofessional unionism began, how might we read some of these goals? Do paraprofessional chapters today (recognizing that constitutions may well have been revised) fulfil these objectives?

- Much of the rest of this document is administrative, but can be used to discuss how power, grievances, and governance are structured in local unions.

3 Comments

Comments are closed.